Both the Qur’an and later sources mention a mysterious city called Iram of the Pillars. Today, it is more flamboyantly called the Atlantis of the Sands. Like Atlantis, it supposedly lies submerged — in this case, beneath the Arabian Desert. But despite promising leads, Iram of the Pillars remains undiscovered.

Background

The original passage in the Qur’an reads: “Have you not considered how your Lord dealt with ‘Aad – with Iram – who had lofty pillars, the likes of whom had never been created in the lands.”

Atlantis of the Sands, as depicted in the video game Uncharted 3. Photo: Uncharted 3/Naughty Dog

The idea of a deity destroying a sinful city is not new. The Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism, and Islam) all include stories of this type. In Islam, Iram was supposedly home to the Ad people. The city was built by a king named Shaddad, a descendant of the biblical figure Noah.

But this king grew greedy and opulent, forcing the prophet Hud to warn him of Allah’s dissatisfaction. King Shaddad and the Ad people disregarded the prophet’s warning. As a result, God buried the city beneath the sands of the Empty Quarter in the Arabian Desert. The sandstorm lasted eight days.

What’s in a name?

Scholars and poets often associate Iram with other names, particularly Ubar and Wabar. Both names make appearances in ancient and medieval scholarship, yet tell the same tale of an affluent city submerged by Allah beneath the sands.

However, some argue that Iram/Ubar/Wabar refers to a whole region, depending on one’s interpretation or translation of the Qu’ran. Credit for its nickname, Atlantis of the Sands, goes to T.E Lawrence.

Lawrence of Arabia in 1919. Photo: Lowell Thomas

The mythical city inspired the famous Uncharted video games and writers like H.P. Lovecraft. Most famously, One Thousand and One Nights spoke of Iram as a city, mentioning King Shaddad’s greed for building palaces entirely of gold and precious stones.

Locations and theories

The Ebla Tablets, an ancient collection of trade inventories, ledgers, and other economic records, mention the city several times. Italian archaeologist Paulo Matthiae discovered the tablets in the ruins of a palace in Ebla, Syria in the 1970s. The tablets date back to 2500 BC. However, the tablets do not mention a location.

In 1930, English explorer Bertram Thomas traveled to the Empty Quarter, also known as Rub ‘al-Khali. His guide told him of a “road to Ubar…a great city, rich in treasures,” and that “it now lies buried beneath the sands of the Ramlat Shu’ayt in northern Dhofar.” The expedition found camel tracks worn into rock that suggested a possible past trade route. But the explorers unearthed no archaeological evidence.

A subsequent search by Harry St John Philby found some compelling geological evidence. His Bedouin guides showed him the Wabar meteor impact craters, which contained meteoritic iron. They told him that God punished the Ad with fire from Heaven. This led him to believe that a meteorite destroyed the city. Unfortunately, he later discovered that this meteor struck the area only a few decades before his visit.

In 1953, Wendell Philips followed the ancient camel tracks discovered by Bertram Thomas for over 30km until they disappeared in the mountains of sand.

Radar leads to some artifacts

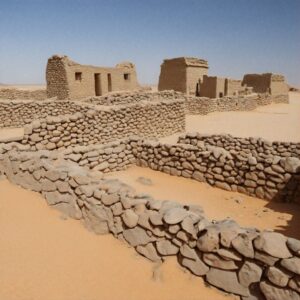

In the 1990s, with the assistance of NASA, Nicholas Clapp and his team got a clearer picture of the landscape using radar. They observed a limestone sinkhole at a place called Shisur in Dhofar, Oman. The sinkhole contained pottery, walls, and pillars that date back to 1000 BC.

NASA released a presumptuous statement that the team had found the fabled lost city. But academic reactions were lukewarm. While Shisur seems the main contender for Iram’s location, several scholars expressed their hesitancy because of the site’s size. They consider it too small to be a city.

Other theoretical locations include Alexandria and Damascus, but these possibilities remain unexplored.

The Empty Quarter. Photo: Kertu/Shutterstock

Archaeologist Juris Zurins favors the theory that Iram was a region rather than a people or city. Zurins backs up his claim with a Ptolemaic map which includes an area called “Land of the Lobaritae”. He believes that this region declined because of natural disasters and poor economic conditions.

The takeaway

In his book The Road to Ubar: Finding the Atlantis of the Sands, Nicholas Clapp explains that some explorers set off on a wild goose chase, based solely on rumors. He said Bertram Thomas’s “knowledge of Ubar came from his not-known-for-their truthfulness Bedouin companions”. He mentions Phillp’s expeditions, where the Bedouins promised to show him the ruins of the city. Eventually, they confessed that they had only heard about it from their grandparents.

But did it ever exist? The heart of the matter lies in what Iram or Ubar means.

The lack of firm evidence may point to Iram not as a city but as something else. Author Paul Neuenkirchen suggests that “the name Iram might have originated from a foreign language and meant other words like nation, tribe, ancestor, or could have referred to tribes like the Bedouin.”

Since the Qu’ran carries an array of interpretations, translations, and versions, the story could have been warped over the last thousand years. Therefore, the confusion may stem from an ancient linguistic issue. Once the word’s true meaning is established, we can go about finding whatever hides beneath the rolling sands of Arabia.