We’ve all heard of El Dorado. The fabled lost city in South America, built of solid gold and ruled by a king so rich that he was covered head to toe in gold dust, has burrowed itself into the mind of many explorers since the 16th century. Ship captains, conquistadors, soldiers, and mapmakers dared the treacherous jungles in search of it, but to no avail. In the late 1500s, treasure hunters turned their attention to a mythical body of water, supposedly near El Dorado or even the lake upon which it was built, Lake Parime became their next fixation.

Deconstructing the myth

Before we get to Lake Parime, let us deconstruct the El Dorado myth. Where did the story come from? The name El Dorado did not originally refer to a city; the name comes from Spanish explorers and translates into “the golden one.” The golden one was supposedly a man completely covered in gold, obscenely rich, or a powerful leader.

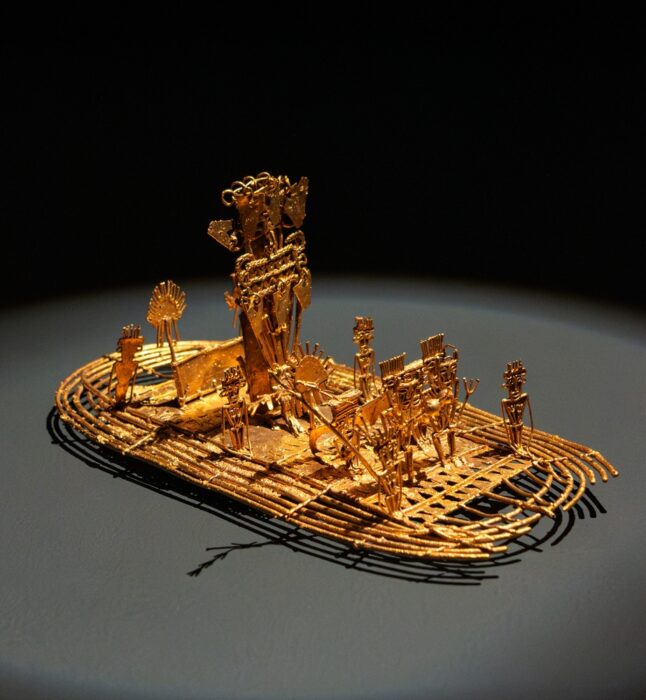

Muisca raft depicting the ritual. Photo: Shutterstock

Rumours of gold had been circulating amongst explorers since at least 1529. The early expeditions of German conquistadors Ambrosius Dalfinger and Nikolaus Federmann recorded their encounters with tribes in the interiors of Venezuela who possessed plenty of gold and precious jewels. In 1534, Spanish conquistador Sebastián de Belalcázar mentioned an encounter with a mysterious man dressed in gold ornaments or armour. He called him “el indio dorado” or “golden Indian.”

However, most historians trace the story of El Dorado to 1541, when a Spanish chronicler and soldier named Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés wrote about a king who conducted a sacred ritual in a lake near Quito, Ecuador. Oviedo said:

They tell me that what they have learned from the Indians is that a great lord or prince goes about continually covered in gold dust as fine as ground salt. He feels that it would be less beautiful to wear any other ornament…he washes away at night what he puts on each morning, so that it is discarded and lost, and he does this every day of the year.

Further information came from the writings of Juan de Castellanos, a conquistador who became a priest. In the 1570s, he wrote Elegías de varones ilustres de Indias, and identified the king as a cacique or zipa (leader) of the Muisca, a culture that resided in the Altiplano Cundiboyacense region of the Colombian Andes. Castellanos said that the lake in which this leader cleansed himself was Lake Guatavitá, 57km northeast of Bogotá.

The king cleansed himself in the sacred waters, and the villagefolk would toss in an array of gold pieces, jewels, and other treasures as an additional offering to their gods. Today, a depiction of the ceremony is captured in the Muisca Raft, an intricate golden object that the Muisca cast between 1295 and 1410 AD, which now resides in the Museum of Gold in Bogotá, Colombia.

As the Spanish continued to descend upon the continent, it was not long before they caught wind of this incredible story. Conquistadors searched the lake but only found a handful of gold pieces. In 1541, Gonzalo Pizarro (brother of famed conquistador Francisco Pizarro) set out with a large expeditionary force of 4,000 natives and over 300 conquistadors in search of El Dorado. However, he failed miserably, and they returned empty-handed.

Over time, El Dorado was used interchangeably to describe a city, a king, or the lake.

Sir Walter Raleigh and Lake Parime

Sir Walter Raleigh’s portrait in 1588.

Sir Walter Raleigh searched for El Dorado up the Orinoco River in the 1590s. He had heard about El Dorado from the former governor of Trinidad, Antonio de Berrío, whom he captured when he landed on the island. Berrío had searched for El Dorado but failed.

According to Raleigh, during his exploration of Guiana, he heard about the city of Manoa and natives laden with gold:

I have been assured by such of the Spaniards as have seen Manoa, the imperial city of Guiana, which the Spaniards call El Dorado, that for the greatness, for the riches, and for the excellent seat, it far exceeded any of the world, at least of so much of the world as is known to the Spanish nation. It is founded upon a lake of salt water of 200 leagues long, like unto Mare Caspium.

I asked the manner how the Epuremei wrought those plates of gold, and how they could melt it out of the stone; he told me that the most of the gold which they made in plates and images was not seuered from the stone, but that on the lake of Manoa, and in a multitude of other rivers they gathered it in grains of perfect gold and in pieces as big as small stones.

One of Raleigh’s colleagues, Lawrence Kemys, was the first to write about Lake Parime:

…afterwards they return for their canoes, and bear them likewise to the side of a lake, which the Iaos call Roponowini, the Charibes, Parime: which is of such bigness, that they know no difference between it and the main sea.

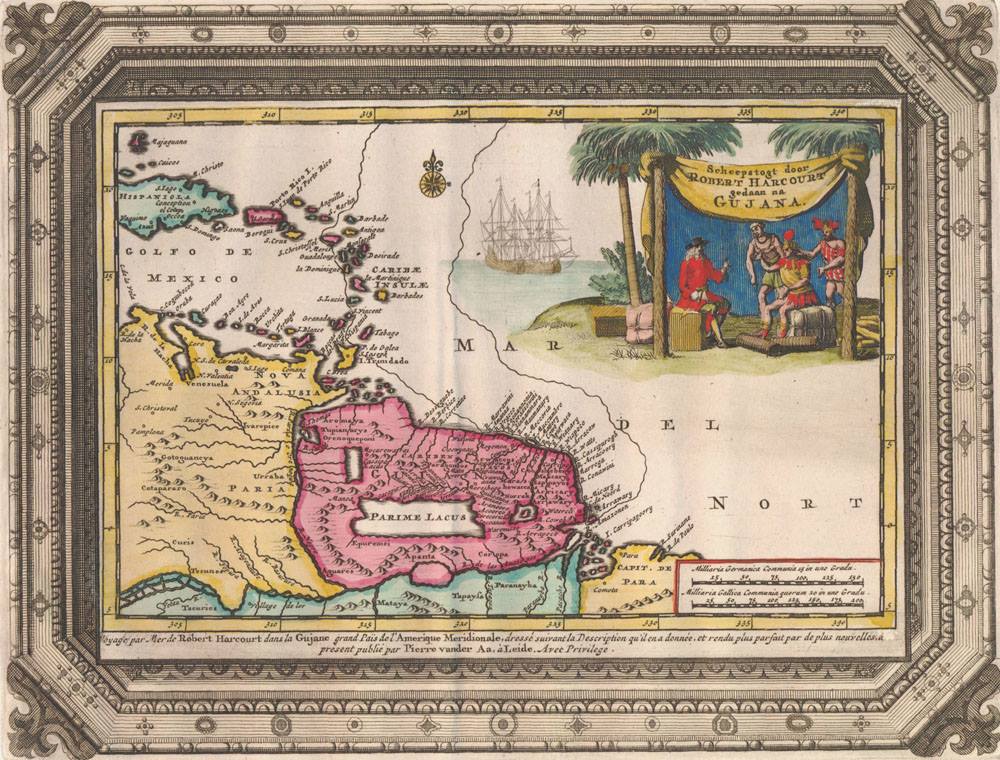

Kemys placed Lake Parime near the Essequibo River. As a result of these writings, some cartographers placed El Dorado and Lake Parime in Guyana. In the 17th century, English cartographer Robert Morden published Geography rectified; or, a description of the world, stating that:

The country about the Lake Parime, in the middle of Guyana, acknowledge, by report, a successor of Guainacapa of the House of Incas of Peru, and compose the true Kingdom of the Golden King.

N. Sanson’s map of Lake Parime, 1656. Photo: N. Sanson

Theories

Expeditions in subsequent years began to shed light on why explorers couldn’t pin down the lake’s location. An expedition led by Alexander von Humboldt found that no such lake exists, leading him to believe the “lake” was the result of the Rupununi Savannah flooding during the rainy season. The Rupununi floods every year from May to August. English naturalist Charles Waterton supported this explanation after natives told him that Lake Parime did not exist.

Fast forward to the 1970s, and explorer Roland Stevenson hoped to put the matter to rest. His travels took him to Roraima rather than Rupununi. He learned of a sacred road called “Nhamini-u” that featured numerous Inca petroglyphs and artefacts. His exploration of the road led him to the supposed water line of an ancient lake. He believed the lake disappeared and drained into the larger Rio Branco because of tectonic activity in the area. Scientists determined that it was possible that a lake formed there during the Paleozoic era.

It seems likely that early explorers, after witnessing local rituals, overestimated how much gold the native cultures possessed. Additionally, locals may have led the conquistadors on a wild goose chase, mixing fact and fiction.