In 1885, tightrope walker-turned-explorer William Leonard Hunt was searching the Kalahari Desert for diamonds when he found a different kind of treasure in some rocky terrain: ruins of what he said was an ancient civilization. Did he really stumble on a lost city buried beneath the sands? He thought so.

Hunt’s story lives on today and has inspired dozens of expeditions to search for the ruins, including several by Elon Musk’s grandfather.

Tightrope walker turned explorer

Today, William Leonard Hunt is mostly known for his colorful resumé. He walked across Niagara Falls on a tightrope, built the machine used for the world’s first human cannonball stunts, and collaborated with circus impresarios like P. T Barnum and William C. Coup.

A restless soul, he bounced from occupation to occupation. In 1885, he briefly left show business to chase fantasies of riches in remote places. He was drawn to the Kalahari Desert in South Africa and became the first white man to traverse it.

He set off from Hopetown with his adopted son and photographer Lulu, two African workmen, and two guides named Kurt and Jan Abrahams. Hunt himself posed as a Canadian explorer named Guillermo Farini. The company experienced many highs and lows during the expedition, including encounters with both dangerous animals and suspicious local people. Once, they almost died of starvation.

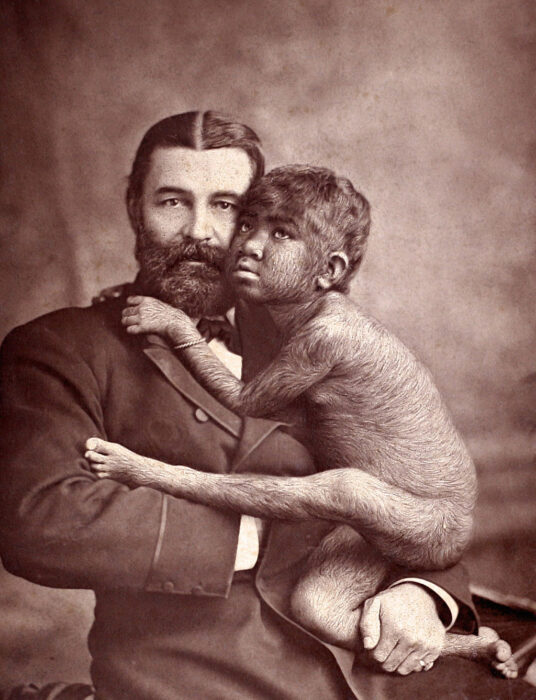

William Leonard Hunt with his adopted daughter Krao. She was from Laos and had a rare skin condition. He promoted her at exhibitions as the missing link between apes and humans. Photo: W&D Downey

The city?

After crossing the Molopo River between present-day Botswana, South Africa, and Namibia, they ended up very lost. Eventually, the team came across some stones that looked expertly cut, as if by a mason. They were square-shaped with sharp right angles. To Farini, they looked like ruins.

In his book, Through the Kalahari Desert, he says the ruins “formed an arc, inside which lay at intervals of about forty feet apart a series of heaps of masonry in the shape of an oval or obtuse ellipse…”

Additionally, he says, “We camped near the foot of it, beside a long line of stones which looked like the Chinese Wall after an earthquake…[and] proved to be the ruins of quite an extensive structure…”

Apart from the rock formations, he found nothing else: no artifacts, no signs of human settlement. Either this supporting evidence remained buried in the sand, or this was not a ruin of a city.

Yet he was adamant that he had found something significant. He managed to publish his discovery through the Royal Geographic Society, along with the expedition’s photographs. Interestingly enough, this flamboyant character did not go to the press to claim this great triumph.

Theories

He had several theories for these structures. He proposed a “city or a place of worship or the burial ground of a great nation, perhaps thousands of years ago.”

However, in 1964, explorer and author A.J. Clement claimed to have debunked Farini’s lost city as a disappointing case of dolerite rock. He found these rocks near the town of Rietfontein, where they were called the Eggshell Hills. This igneous rock forms when magma penetrates other types of rocks deep underground and cools quickly, forming a column of stronger and differently colored rock.

Basalt columns of Giants Causeway in Ireland. Photo: Shutterstock

Walls of dolerite build up via columnar jointing and present almost perfectly angled fractures. It looks very similar to the more familiar columnar basalt, which we see in examples all over the world, including Giant’s Causeway in Ireland, Fingal’s Cave in Scotland, and Devil’s Postpile in California. Dolerite also has a crystalline appearance, which people could mistake for building material. This part of South Africa has a high concentration of dolerite.

Red sands of the Kalahari Desert. Photo: Sebastian 22/Shutterstock

Given that Farini was prone to exaggeration, made up false identities, and had a career in show business, it would not be surprising if he reached an unwarranted conclusion based on a geological curiosity he didn’t understand.

Conveniently, he did not provide the exact route or landmarks with which to find this “city.” This does not lend much credence to his story, either.

Counterpoint

The Kalahari may be a difficult climate in which to establish a city or civilization, but it is not impossible. There are various ancient settlements and archaeological sites scattered across the Kalahari, like Kweneng and Ditsobotla in Botswana. The city of Kweneng dates to the 1400s and was buried beneath vegetation in Suikerbosrand National Park in South Africa. It was discovered via Google Earth and LiDAR. This city was a trading hub between the 15th and 19th centuries. Was Hunt’s lost city something like this?

Around the world, deserts have managed to host advanced civilizations. Beginning around 1000 BC, the Garamantes lived in the Sahara and became one of the first urban societies to thrive in a desert. Likewise, many Native American tribes lived in the southwestern United States. In the Arab world, the Bedouin adapted to harsh climates for thousands of years. It can be done.

However, to sustain a larger city would be a challenge. Water sources are modest and too far away. A nomadic lifestyle makes more sense. Building permanent structures would not have been a priority.

Other expeditions

Over the years, some 30 expeditions have attempted to find it. In 1933, Professor E.H.L. Swartz, F.R. Praver, Dr. W. Meent Borcherds, and two or three others traversed the region but came back empty-handed. They found limestone formations but doubted that these were the city. In 1936, Lawrence Green tried retracing the 1933 expedition and found limestone as well.

A village in the Kalahari. Photo: Lulu Farini

An unlikely individual who combed the desert in search of this lost city was none other than the grandfather of Elon Musk. Yes, the grandfather of the CEO of SpaceX, Telsa and X (formerly Twitter) took part in this quixotic search. His name was Joshua Norman Haldeman, and he was a chiropractor. He took his family, including Musk’s mother, on an expedition every July for three weeks, according to CNBC. This tradition started in 1953, and they went on 12 expeditions over the years. Haldeman even flew over the Kalahari, looking for signs of the ruins.

The Travel Channel’s reality series Expedition Unknown covered Hunt’s Kalahari story. Its team traveled along the Oranje River and didn’t find the city but turned up art etched onto rocks. Host Josh Gates stated, “Analysis of the early rock art and stone structures we examined confirms that they were made more than a millennia ago…”

Still, as of today, there is no evidence to suggest that the Kalahari hosted a lost civilization. But as LiDAR and other technology help rediscover previously elusive ruins, there is a small chance of finding something beneath the sands.

Conclusion

What can we take away from this? Farini was an entertainer and perhaps an exhibitionist who might have been disposed to jump to conclusions. Yet he also lived in a time of great discoveries in archaeology. Africa, in particular, had many secrets to tell.

As there was no other evidence besides the rock formations, it is safe to conclude that he was describing some natural rock formations. But Farini did leave behind a story that, at least culturally, remains something of a treasure.