On Oct. 11, 1809, in a small inn named Grinder’s Stand, along an ancient trail called the Natchez Trace, a great man died too young.

This in and of itself is not unusual. It was an age of sub-optimal healthcare, privations, hardships, and violence shocking to our modern sensibilities. Early deaths were not uncommon, and the man in question had lived a difficult life in his last few years. But his status as one of early America’s first and most notable celebrities meant his passing did not go unnoticed. The mystery surrounding his death confounded his contemporaries and continues to trouble historians right up until the present.

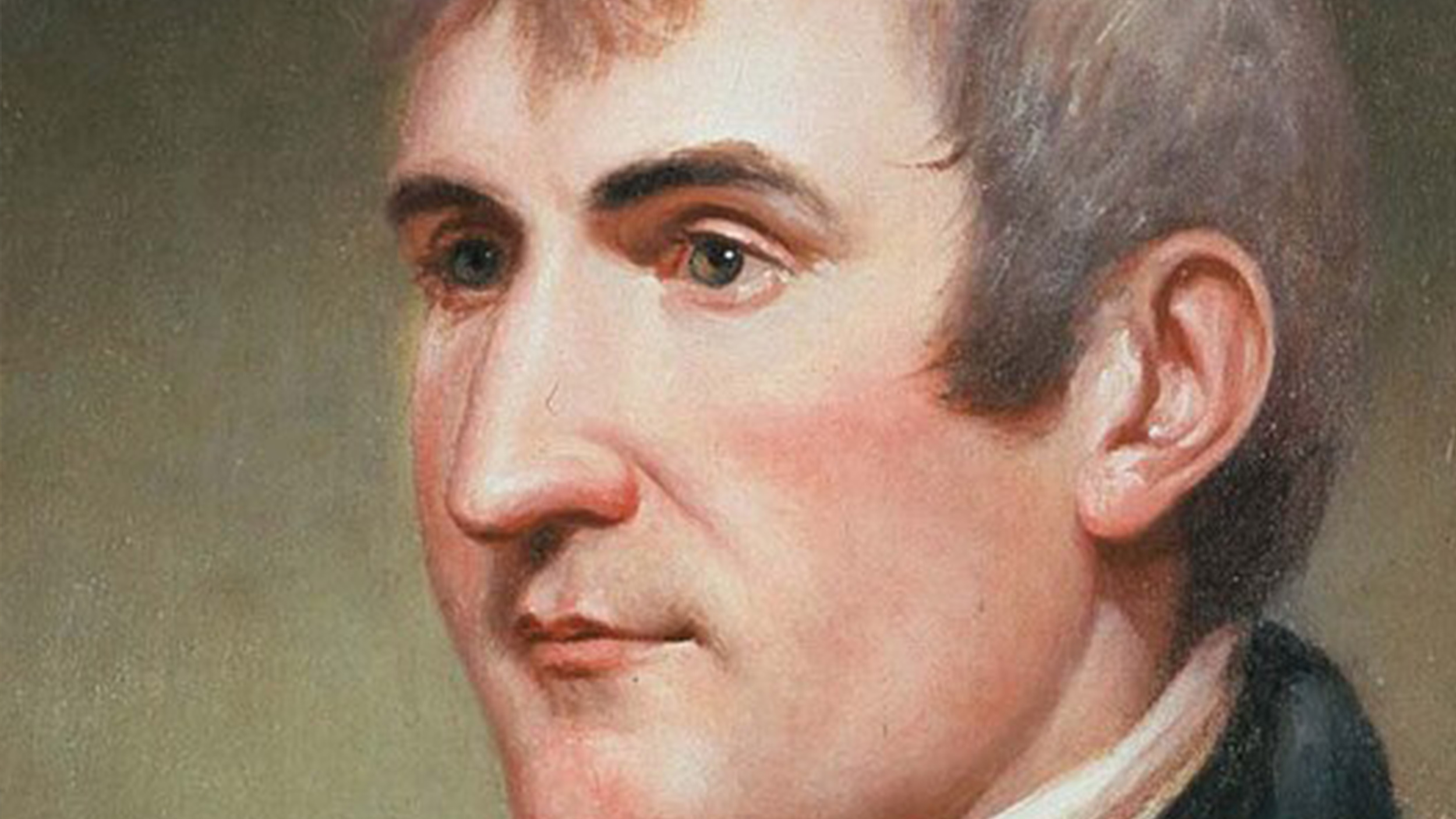

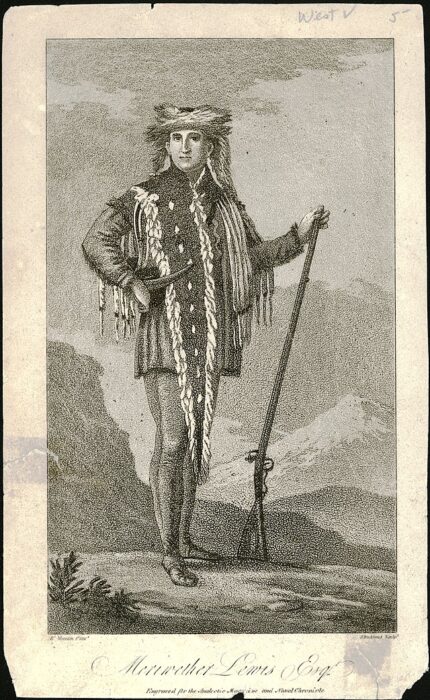

The man was Meriwether Lewis, half of the leadership team of the famous Corps of Discovery. Along with Capt. William Clark, Lewis helmed an expedition totaling 42 hardy souls as they embarked from St. Louis at the behest of President Thomas Jefferson to reach the Pacific Ocean via an overland route. The Corp’s official job was to discover a navigable East-West waterway across the North American continent.

This mission was a bust, stymied by the imposing Rocky Mountains. But the Corps of Discovery reached the Pacific and returned home with only one death among their party. Along the way, they collected reams of scientific data on the people, plants, animals, and landscape that lay west of the Mississippi River, a body of work that ignited the American imagination. For good or ill, Lewis and Clark’s journey was the beginning of Manifest Destiny — the idea that a young America was destined to fill the interior of the North American continent from sea to sea.

A 1905 painting by Charles Marion Russell showing the Corps of Discovery on its journey west. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Instant heroes

Upon the Corps’ return in 1806, the men involved instantly became heroes. Some two hundred years later, most Americans and many others around the globe have at least a passing familiarity with the Lewis and Clark Expedition. This journalist even named his cat after Lewis.

But far fewer know of Meriwether Lewis’ unhappy fate in a grimy inn perched upon an old, old trail a mere three years after his epic journey made him a household name. It was an ignominious end. Lewis was discovered in his room, alone, with gunshot wounds to the head and chest. He died a few hours later.

Was it depression-fueled suicide? A robbery gone wrong? A murder fueled by some kind of grudge (political, personal, or both)? All are theories floated by Lewis’ contemporaries shortly after his death, and all those theories, plus a few others, persist today.

And while most historians — such as Stephen Ambrose, author of the classic Lewis biography Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West — favor the suicide theory, other academics leave room for the murder/robbery theory. Still others argue that a combination of diseases caused a deranged Lewis to inflect self-harm simply to escape overwhelming physical pain.

Like so much of history, we’ll likely never know for sure. But we can honor Meriwether Lewis’ life by examining his death. Final chapters, however unpleasant, must not go unread.

Despondancy and malaise

Humans who accomplish great works are often faced with crushing depression once those works are complete. This is true of everyone from painters to explorers and everyone in between. How do you face the knowledge that you have likely achieved the greatest thing you will ever achieve?

Alexander the Great’s heavy drinking accelerated dramatically in the years following the end of his famous conquests, and many artists sink into despair after finishing particularly stupendous work. I’m a long-distance backpacker, and the year after I completed the 3,500km Appalachian Trail was one of the most difficult mental-health moments of my life. Other examples abound, particularly if the people in question already suffer from what we today call clinical depression.

Before Jefferson tapped Lewis to lead the Corps of Discovery, the two men enjoyed a close personal friendship. Lewis was Jefferson’s secretary, and perhaps no man knew him better. Jefferson described Lewis as experiencing “occasional depressions of the mind.”

So Lewis definitely had depression, and it doesn’t take a great empathetic leap to understand that condition may have been particularly hard to escape in the years following his return from the West.

Other factors

Additionally, Lewis was overwhelmed by the task of preparing his journals for publication. His brief political career as the governor of the Louisiana Territory had gone poorly, and his debts were mounting. In fact, he was traveling to Washington, D.C., to try to resolve those debts when he stopped at Grinder’s Stand for the night.

As the scientific literature around post-traumatic stress disorder becomes more fleshed out, others are pointing toward that condition as a possible factor. While the Corps’ mission was a success on almost every front, and Lewis and Clark only lost one man — an astounding feat given the adventures and hardships the group endured — it was undeniably traumatic. The Corps, by necessity, likely formed extremely tight bonds, bonds that dissolved once they went their separate ways. It was not an age that made it easy to stay in close contact with people scattered around a continent.

Lewis also struggled romantically post-Corps of Discovery. Finally, according to Stephen Ambrose, Lewis’ long friendship with Jefferson was on the rocks, and he was drinking heavily (and possibly using opium, although this is debated).

A photo of the Meriwether Lewis National Monument taken in 1936. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Coroner’s inquest

That’s a potent combination of factors for a man already struggling under the weight of depression.

So it’s entirely likely — most historians would say probable — that when Priscilla Griner, the innkeeper’s wife, heard gunshots in the hours before dawn and sent servants to investigate, it was Lewis’ own hand that had pulled the trigger. Lewis bled out on his buffalo skin robe, a souvenir from his westward journeys. He was 35 years old.

A coroner’s inquest conducted shortly after the incident failed to charge anyone with a crime, and the two men who knew him best — Jefferson and Clark — were, as is all too common with the survivors of suicide, unsurprised. Adding to the evidence is the fact that Lewis completed his will shortly before beginning his journey to D.C.

All of the above leads Ambrose and other students of Lewis’ life to rule suicide as the most likely cause of his death.

Disease and pain

A related line of thinking agrees with the suicide theory but supports different underlying causes.

Author Thomas Danisi, in papers and in talks presented to various Lewis and Clark associations, has posited that a severe case of malaria caused derangement and intense pain, enough so that Lewis, in a moment of fever-induced mania, turned to his gun to relieve his symptoms.

Could a malaria-carrying mosquito like this one have contributed to Meriwether Lewis’ death? Most historians doubt it. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It’s not entirely outside the realm of possibility. In one of the oral accounts Priscilla Griner left behind, she reported that Lewis appeared flushed and physically out of sorts at dinner the night before his death and was even mumbling to himself and pacing restlessly.

But it’s worth noting that Danisi is a self-described “independent researcher” with no history degree — he graduated from St. Louis University with an English degree in 1973. Your mileage, as they say, may vary.

Murder and robbery?

Lewis’ family — quite understandably — has long held that his death was not a suicide but was instead a murder or perhaps a robbery gone wrong.

This speculation is fueled by a lack of reliable first-hand accounts by those present at the death. Priscilla Griner never left a written account of what she witnessed, and her oral accounts were compiled years later. Often they contradict each other. In one, she claims she heard a scuffle and a cry for help after the two gunshots. In another, she says that three men followed Lewis along the Natchez Trace, and that Lewis had challenged them to a duel earlier in his journey. The chronology of these events changes from account to account, as does the time when she discovered the wounded Lewis.

Irresponsible journalism also muddied the waters. One local newspaper claimed that Lewis’s throat had been cut, and as the story spread, newspapers across the country exaggerated or inflated other elements of Lewis’ death. Exacerbating the robbery story is one claim that a sum of money Lewis had borrowed to complete his journey was missing from his personal belongings.

Both Lewis’ surviving relatives at the time and his distantly related ancestors have embraced the murder theory. But historians must traffic in the facts they have and logically fill in gaps left by primary sources, not make speculations based on unreliable information. In light of the overwhelming consensus that he died by suicide, it’s hard not to read the murder theory as first a grief reaction, then an attempt to preserve Lewis’ historical legacy.

But what about forensic evidence? Can a modern examination of Lewis’ body finally solve some of these riddles?

A historical mystery, destined to remain unsolved

The short answer is probably. The first doctor to examine Lewis’ body did so in 1848 when the state of Tennessee exhumed the corpse in the process of building a monument to Lewis. That doctor fanned the conspiracy flames by concluding that “it seems to be more probable that [Lewis] died by the hands of an assassin.”

Still, medical knowledge, particularly forensic science, has advanced greatly in 176 years. Modern scientific examinations could likely reveal much. Lewis’ descendants, through his sister Jane, have long lobbied for another look at the body.

The problem is that Lewis’ gravesite is a national monument, meaning the United States National Park Service has to approve the exhumation. In 1998, the Park Service denied the request, citing possible disturbances of other gravesites in the same area.

The Meriwether Lewis National Monument and Gravesite. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Why does it matter?

In 2008, the Department of the Interior (the parent agency of the Park Service) approved the request but changed its mind in 2010 before archaeological work could begin. The reasons behind these decisions are opaque and shrouded in governmental bureaucracy.

Unless something changes, we’ll likely never know for sure what happened to Meriwether Lewis. So we are left with a final thorny question: Why does it matter?

It feels difficult to draw any lessons from Meriwether Lewis’ last moments. One is struck by overwhelming despondency when considering the final end of a man who, despite his apparently obvious struggles with depression, managed to accomplish so much in his short life. This is particularly so when paging through Undaunted Courage, where the reader must face the contrast between vibrant accomplishments and bitter endings in short order.

Still, there is the act of bearing witness. Sometimes, all we can do when faced with tragedy is observe it and remember it. From this standpoint, it does matter how Lewis met his death.

In unraveling this mystery — or, at the very least, considering the mystery — we might bring a measure of peace in death to the memory of a man who had precious little of it in life.