When Lewis and Clark led the Corps of Discovery toward the Pacific from St. Louis, they were venturing into unknown territory with little idea of what they’d find over the next prairie horizon.

Right?

Not exactly. Buried safely in a bag was a book — an English translation of a French memoir that gave the Corps a solid idea of their route and many of the geographical features they’d have to navigate along the way. But where did this book come from? Had someone already traveled from the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi, across the Rockies, down the Columbia, and back?

The answer is maybe. But if anyone did, it was no one of European descent. Rather, it was a Yazoo man named Moncacht-Apé — a multi-lingual wanderer blessed with relentless curiosity concerning the history of his people. That curiosity may have led Moncacht-Apé to dip his toes into the Pacific nearly a hundred years before Lewis and Clark reached those same waters.

Moncacht-Apé’s story is intertwined with that of Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, a French naturalist, ethnographer, and historian who lived in the Louisana Territory for 16 years. And without Le Page’s own curiosity, the tale of Moncacht-Apé’s journey across North America might have been lost to history.

A history of the Louisiana Territory

Le Page was a man in the classic early enlightenment mold. Born in 1695 and educated as an engineer and architect, he saw action with the French army against Germany in the War of Spanish Succession. At the age of 23, he picked up stakes and headed to the Louisiana Territory to seek his fortune. He eventually wound up in Natchez, on the banks of the Mississippi River, where he cultivated tobacco (or rather, his two slaves did). He swiftly learned the Natchez language and set about his hobby — cataloging the oral traditions of the Natives whose land comprised the Louisiana Territory.

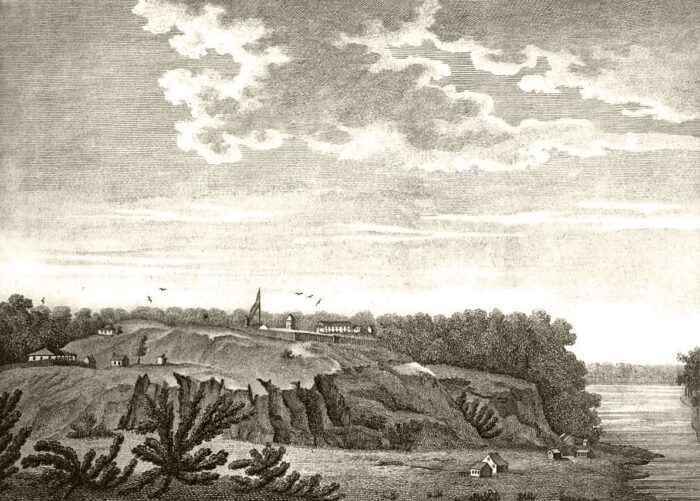

The fort at Natchez as it would have appeared in Le Page’s time. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Enter Moncacht-Apé

Sometime before the outbreak of the Natchez War in 1729, Le Page made the acquaintance of Moncacht-Apé, an elder of the neighboring Yazoo tribe. The local French called the man “Interpreter” because of his encyclopedic knowledge of languages. As it turned out, Moncacht-Apé’s linguistic skill was hard-earned.

Le Page was interested in the history of people who called the region home, and Moncacht-Apé was introduced as the person most knowledgeable about the subject. This historical curiosity was a trait shared by the two men.

The Yazoo and neighboring tribes had oral traditions that indicated they’d migrated from the West. Some 30 to 40 years before he met Le Page, Moncacht-Apé set out to test the veracity of those tales on a long journey that — according to him — took him all the way to the Pacific, then back home. According to Le Page, Moncacht-Apé’s name translates as “the killer of pain and fatigue.”

The no-doubt-stunned Le Page recorded Moncacht-Apé’s story in great detail and, unusual for the time, in the man’s own words, with little editorializing.

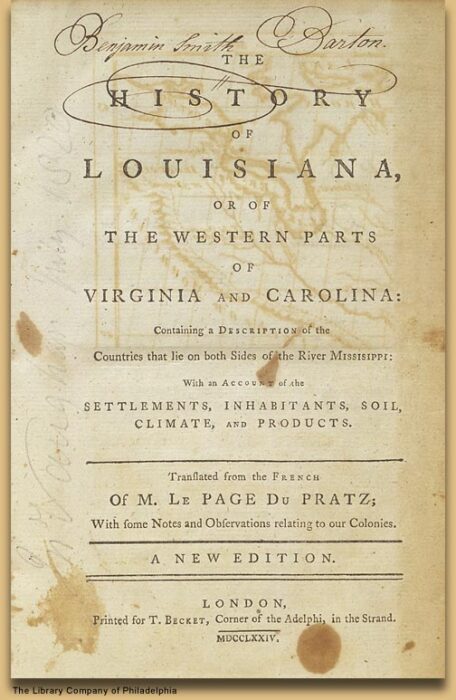

The title page of a later English edition of Le Page’s book. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“I begged him to repeat to me an account of his travels, omitting nothing,” Le Page later wrote.

Seventeen years after immigrating back to France in 1734, Le Page published a sprawling volume called History of Louisiana. Moncacht-Apé’s tale comprised three chapters of the manuscript, the longest Le Page spent on any subject in the book. It was a partial (and unfortunately, heavily abridged) translation of this work that accompanied the Corps of Discovery on its famous trek in 1804.

‘Beautiful River’

In the original editions of Le Page’s work, Moncacht-Apé began his journey by traveling up the Mississippi and then the Missouri until he reached the Kansas nation. There, linguist that he was, he learned the local tongue and gathered information about his next steps. The locals told him it would take another month to reach the headwaters of the Missouri, and from there, he should walk north until encountering a westward-flowing “Beautiful River.”

The confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers was a starting point for many westward expeditions. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Moncacht-Apé did just that, then traveled downstream until he encountered the Otter people. He paddled with the Otter for a while, learning their language, then continued solo for another 18 days until he reached an unnamed tribe living in a “grassy land with many dangerous snakes.” He wintered with these people, then resumed his journey in the spring, eventually reaching the coastal tribes, whom he describes as living mostly on fish.

Notably absent from this account are the Rocky Mountains. It’s one of the major holes in the story, and a chief feature that has led some historians to question the tale. Lewis and Clark also had no idea the Rockies were going to be a problem — Lewis had designed and packed a foldable boat for what he assumed would be a relatively short and easy portage from the Missouri to the Columbia.

A traveler joins a battle

On the shorelines of the Pacific, Moncacht-Apé encountered Natives who were in conflict with European loggers.

“I was told that these men were white; that they had long, black beards which fell upon their breasts; that they appeared short and thick, with large heads, which they covered with cloth; that they always wore their clothes, even in the hottest weather; that their coats fell to the middle of the legs, which as well as the feet were covered with red or yellow cloth. For the rest, they did not know what their clothing was made of because they had never been able to kill one, their arms making a great noise and a great flame,” Moncacht-Apé relayed to Le Page.

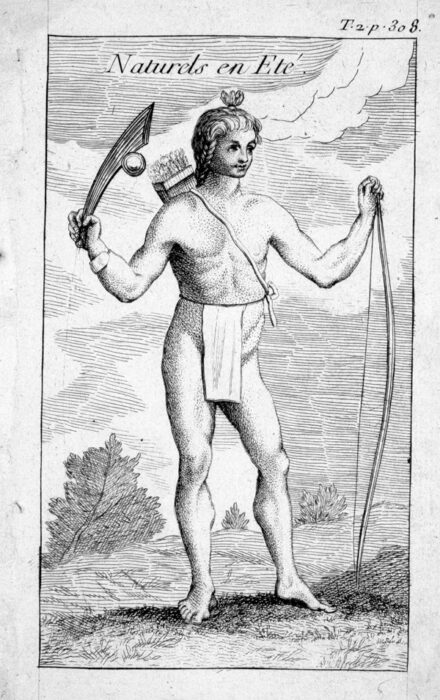

An illustration from Le Page’s book. Photo: Public Domain

But Moncacht-Apé was well-versed in the use of firearms, and he joined the conflict against the loggers, eventually turning the tide. According to Moncacht-Apé, he led a group of Natives in a surprise attack that killed 11 of the Europeans. Then he traveled along the coastline north, gathering tales along the way. One of the stories he collected seems to verify the land-bridge theory — the idea that the New World’s Indigenous people originally immigrated across the once-dry Bering Strait in the distant past.

“One of [the elders I encountered] added that when young, he had known a very old man who had seen this land (before the ocean had eaten its way through), which went a long distance, and that at a time when the Great Waters were lower (at low tide), there appear in the water rocks which show where this land was,” he recounted.

Moncacht-Apé eventually returned home safely and was an old man by the time he encountered Le Page. What happened to him after Le Page returned to France is unrecorded.

Historical veracity

Le Page is the only source historians have for Moncacht-Apé’s tale, and they’ve been busily debating its veracity ever since Le Page first published his manuscript.

The absence of the Rockies in the tale is a major problem. And with only one source, there’s no way to know if Le Page added to the tale or invented the entire thing (not to mention Moncacht-Apé) out of whole cloth. It’s possible that Le Page could have pieced together the story based on information he obtained from a variety of sources. Adding credence to this side of the debate, later editions included a supplementary tale, which has Moncacht-Apé beginning his quest by first traveling up the Mississippi, east past Niagara Falls, and eventually reaching the Atlantic.

Why would he do this if he was following oral traditions that pointed him westward? And why didn’t it appear in Le Page’s first edition?

Spinning a yarn?

Le Page subscribed to the land-bridge theory before supposedly meeting Moncacht-Apé. It’s certainly possible that the amateur ethnographer invented a handy tale to support preexisting ideas. It’s also possible that Moncacht-Apé really did exist but was spinning a yarn for an eager audience. In this scenario, Moncacht-Apé would have been passing on details he gathered from other travelers.

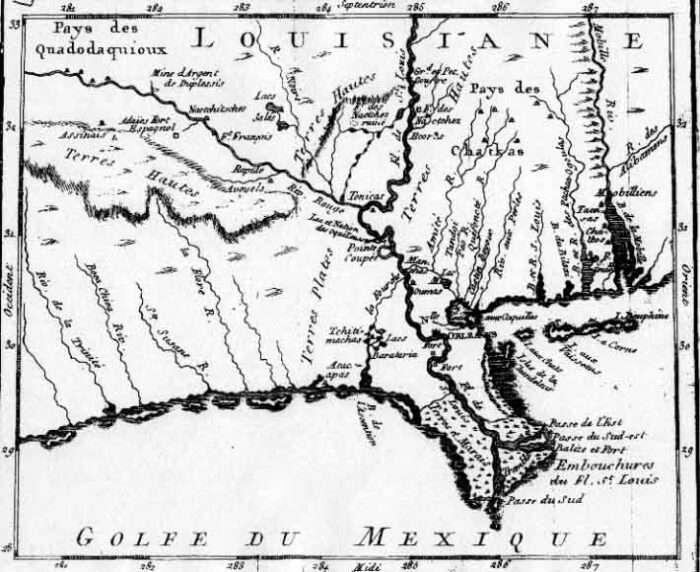

On the other hand, Le Page’s work is noteworthy for his habit of apparently transcribing the oral tales he collected verbatim instead of telling them in his own voice. This was unusual for the time. The maps he published along with his manuscript were more accurate than contemporaries compiled from second-hand knowledge, and many, if not all, of Moncacht-Apé’s descriptions of the people and places he saw along the way eventually proved trustworthy.

One of the maps that appeared in Le Page’s book. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Finally, historians must untangle the latent racism inherent in the age. It would have been difficult for Europeans to accept that Natives possessed the same spirit of exploration as themselves. But of course, we know better. As University of Oregon professor Gordon M. Sayre once put it, “I believe it is possible and even likely that some Native Americans did make such long journeys of exploration. Geographical curiosity is not confined to Europeans.”

A believable account

Assuming Le Page didn’t make up the story out of thin air, he seems to have believed Moncacht-Apé. And a passage from his book foreshadows the coming adventure that the Corps of Discovery would undertake fifty years after he published his work.

“I cannot persuade myself otherwise than that he went along the coast of the…Western Sea. The Beautiful River that he descended is a considerable river, that one should have no difficulty in finding, as soon as one should come to the sources of the Missouri,” he wrote. “And I have no doubt that a similar expedition, if it were undertaken, could fully establish our ideas about this part of North America and the famous Western Sea, of which everyone in Louisiana is talking about and seems to desire so much to discover.”