“Now from the North Of Norumbega, and the Samoed shoar, Bursting thir brazen Dungeon, armd with ice And snow and haile and stormie gust and flaw…”

When I read this in college, I was lost, as you probably are. After all, these lines came from John Milton’s Paradise Lost, one of the most complicated literary works out there. For starters, the name Norumbega went straight over my head until much later.

Norumbega was supposedly a lost land somewhere on the east coast of the United States. According to maps and the fevered writings of explorers and sailors during the Age of Discovery, it was a city whose buildings were made of quartz crystals and precious jewels, and whose inhabitants wanted for nothing. Sounds pretty sweet. Also sounds pretty unrealistic.

Giovanni da Verrazano. Photo: F. Allegrini

Maps, maps, and more maps

This lost land first appeared on the 1529 map of Italian cartographer Giovanni da Verrazano. Verrazano’s patron, King Francois I of France, wanted him to find a western passage to Cathay (China), but after a storm almost obliterated his expedition, he was unable to stick to the original plan. Instead, he opted for an impromptu two-year jaunt (1522-1524) from New Brunswick to Florida.

He visited Arcadia (north of Virginia) and New York Harbor. Most notably, he discovered a “Refugio” of friendly, beautiful natives, fertile land, and pure bliss. This Refugio supposedly lay in what is now Rhode Island. But when he drew his map, he added a curious little land called Norumbega just above the Refugio.

It did not have the name “Norumbega” right away. Rather, it was called Oranbega. Academic sources suggest that the name may have roots in the Algonquian language, where it means “quiet stretch of water.” Some sources suggest that it was a play on the Spanish word oro, meaning gold, because of its subsequent reputation as a gold-laden, indigenous utopia. Years later, the exact location of Norumbega remains a subject of great speculation.

A year after Verrazano’s expedition, Portuguese explorer Estevao Gomes explored Nova Scotia down to Maine and encountered a unique native community in what is now Penobscot Bay. He wrote that the people were:

…great archers, and wear skins of wild beasts and others. The country contains excellent martens of the sable kind, and other fine fur-bearing animals . . .They have silver and copper, as they gave to understand by signs. They worship the Sun and Moon, and share the other idolatries and errors of the natives on the continent.

A German connection?

Based on Gomes’s reports, cartographer Diogo Ribeiro drew his world map. Scholars linked Gomes’s encounter to Verrazano’s. This is rather strange, as Verrazano never highlighted Norumbega as a particularly special place. In his letters to the French monarch, he doesn’t mention it at all. Rather, he was preoccupied with the Refugio. How did Norumbega evolve into such a mythical place?

Giacomo Gastaldi included Norumbega in his 1548 New World map but spelled it “Nurumberg.” Why this Germanic name? Nuremberg was a shining example of a wealthy European civilization of the time. Perhaps he wanted to pay homage to this great city.

From the 1570s to the 1590s, several world maps came out, all mentioning Norumbega. One even located it roughly in Virginia. Apparently, the famed John Smith believed Norumbega stretched from Virginia to New England. However, the maps depicted it as different things: a small town, a metropolis, a country. No one could make up their mind. Yet, they zeroed in on the New England area.

The rumor mill

The myth of Norumbega’s riches comes from an English sailor, David Ingram, who claimed to have walked from Mexico to Nova Scotia in 1568. During his trek, he supposedly visited Norumbega and wrote about the inhabitants’ immense wealth but vicious nature.

“There were precious stones,” he enthused. “Turquoise and onyx and garnet…pillars of quartz crystal and columns of wood wrapped with thin sheets of silver and even of gold…”

He added that the natives were cannibalistic. Unsurprisingly, historians have questioned Ingram’s exaggerated account.

A couple of decades earlier, a man named Jean Allefonsce presented a more realistic view. Writes historian Joe McAlhany: “[Allefonsce] identified a Riviere de Norenbegue that was clearly the same river called Norombegue, which was populated by a noble tribe clearly modeled on the inhabitants of Verrazano’s Refugio…”

During a colonizing mission to Canada in 1542, Allefonsce wrote of the “clever inhabitants” of this Riviere de Norenbegue, who:

…trade in furs of all sorts; the town folk are dressed in furs, wearing sable…the people use many words which sound like Latin. They worship the sun. They are tall and handsome in form…

In this case, he proposes that it’s a trading hub, which fits the narrative of a wealthy community.

Baking powder and Vikings

One man claimed to have all the answers about Norumbega. An eccentric professor of agricultural chemistry, Eben Horsford was a man of many interests. Best known for inventing baking powder, he had a secret obsession: Vikings. We’re not sure when or why he became interested in such a niche topic, but he staunchly believed that Norumbega was the fabled Vinland of Leif Erikson. (This was well before the discovery of L’Anse Aux Meadows in Newfoundland in the 1960s, which was not Vinland, either.)

The eccentric Eden Horsford. Photo: Unknown

In 1890, Horsford announced the discovery of Leif Erikson’s dwelling place, conveniently close to his own Cambridge, Massachusetts home. He supposedly dug nearby and discovered…something. He wrote to a local judge, stating:

It is now nearly five years since I discovered on the banks of the Charles River the site of Fort Norumbega, occupied for a time by the Bretons some four hundred years ago, and as many years earlier still built and occupied as the seat of extensive fisheries and a settlement by the Northmen.

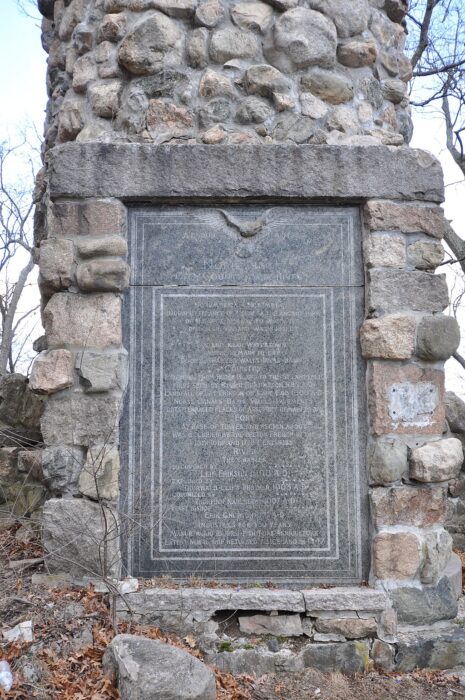

The judge seemed to take it well and wrote back to congratulate him. Horsford commemorated his contribution by installing a plaque and Norumbega Tower, a 12m tall stone pillar. Thereafter, the surrounding areas started to name their local landmarks after Norumbega, imprinting it on the regional culture. In the 19th century, Bangor, Maine, embraced the myth by naming its municipal building Norumbega Hall. Newton has Norumbega Park, and Cambridge carries Norumbega Street. Though there is no physical evidence whatsoever of Norumbega’s existence, New England just rolled with it and celebrated an interesting piece of history…or non-history.

Wacky linguistics

Horsford cited linguistic evidence to those who doubted. He said:

Many hundred years ago, the country we call Norway was called Norbegia and Norbega which are the same philologically -– as we have just seen -– as Noruega or Norvega, or Norwegs; the b is the equivalent of u, or v, or w.”

Hosford then went further to point out that Native American names were actually Norse in origin.

Norumbega Tower, erected by Horsford. Photo: Magicpiano/Wikimedia Commons

Writer Katie C. Berry with the Harvard Crimson brings up an interesting point. She proposed that these crazy ideas came from a rivalry between Protestants and Catholics. Catholics laid claim to the land’s Catholic heritage with Columbus’s discovery. On the other hand, Protestants wanted something else to emulate, in this case, the Vikings.

Conclusion

By the time John Milton came out with those cryptic lines in Paradise Lost in 1667, the myth of Norumbega was well-established. The place may well have existed, although not in the way we think. Lost cities rarely meet our expectations of advanced and spectacularly rich metropolises. Norumbega might have just been a regular indigenous trading hub, whose name and character got misconstrued in the chaos of discovery and hype of New World riches.

As for how Norumbega became associated with a mythical utopia, the world maps produced around the same time as each other might have just copied each other’s place names. Or there may have been several indigenous communities along the coast that later became one singular Norumbega. Certainly, early maps were not the sober, reliable documents, produced from air photos, that we’re familiar with today. Imagination and rumor figured largely in these early charts. If it wasn’t dragons, it was mythical places like Norumbega.