It is 1764, and France is licking its wounds after the Seven Years’ War. The kingdom has exhausted itself financially and lost territory abroad. To make matters worse, intense panic has erupted in the southern countryside, with peasants suggesting a demonic, monstrous creature is attacking people in the fields.

A string of attacks

The first attack occurred in June 1764, when a large, unknown animal attacked a young woman tending cattle near Langogne. She survived only because the bulls in her herd drove the creature away.

A few weeks later, villagers came across the mutilated body of shepherd Jeanne Boulet near a small village in the Lozène region. Boulet’s throat was torn to pieces, but her livestock was unharmed. In July, another teenage victim died in the arms of villagers, but was able to give a brief description of the beast before succumbing to her wounds.

Illustration showing Jacques Portefaix and his friends subduing the beast. Photo: Gallicia Digital Library

Jacques Portefaix and his friends were also tending cattle outside their village when the creature attacked. By some miracle, the boys fended it off. A large group of people seemed to intimidate it.

The story of the beast spread through France and even reached the ears of King Louis XV, who provided Portefaix and his friends with financial support.

Perhaps the most famous incident took place in August 1765. Marie Jeanne Valet was walking across a bridge with her baby sister when the beast charged them. According to legend, Valet stabbed the monster with a knife, and the girls escaped. The incident earned Valet a fierce reputation and the title of the “Maid of Gévaudan.”

There were more attacks, and within a year, the death toll was around 113, with a further 49 injuries.

The beast

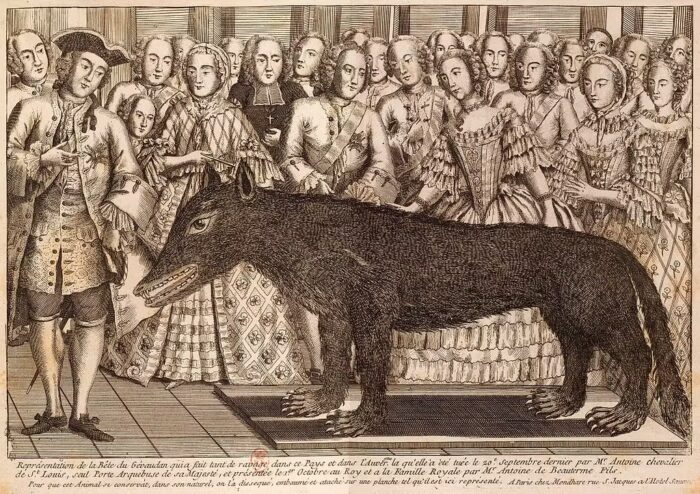

The Beast of Gévaudan on display at court. Photo: Bernard Soulier, La Gazette de la Bête

Posters at the time described the monster as:

Reddish brown with a dark, ridged stripe down the back. Resembles a wolf/hyena but as big as a donkey. Long gaping jaw, six claws, pointy upright ears, and a supple furry tail, mobile like a cat’s, and can knock you over. Cry: more like a horse neighing than a wolf howling.

Historian Jay M. Smith claimed that the creature “could walk on its hind feet, its hide could repel bullets, it had fire in its eyes, it came back from the dead more than once, and it had amazing leaping ability.”

This so-called beast had surprisingly selective tastes. Rather than attacking any living creature, as one might expect from a rampaging predator, it ignored livestock in favor of human prey. Most incidents involved women and children.

The beast was not nocturnal; attacks could occur at any time of day. It had an almost human-like intelligence and avoided traps.

The king intervenes

King Louis sent teams of soldiers and hunters to the region. He enlisted the services of a veteran called Jean-Baptiste Duhamel. Duhamel was an educated and pragmatic man, skeptical of superstitious exaggeration and aware of the need to calm the population.

He decided to recruit local peasants, hunters, and soldiers to form hunting parties. These were extensive, well-coordinated efforts, involving beaters, gunmen, and bait. Duhamel even tried using decoys, dressing men up as women to lure the beast out.

Duhamel’s campaign killed many wolves, but none were definitively the Beast of Gévaudan. The attacks continued, and Duhamel’s failure eventually caused him to be sent away in disgrace.

Frustrated, the king sent hunters Jean Charles Marc Antoine Vaumele d’Enneval and Jean-François to kill the beast. This father-son duo released bloodhounds to sniff out the monster. The bloodhounds killed more wolves but not the beast.

Plenty of wolves, but was any of them ‘The Beast’?

Next, the king dispatched his gunbearer, François Antoine. Antoine killed a large male wolf, stuffed it, and sent it back to the king. Later, he also killed a female and her cubs. He said:

We declare by the present report signed from our hand, we never saw a big wolf that could be compared to this one. Hence, we believe this could be the fearsome beast that caused so much damage.

The attacks continued, but the court, thinking they had solved the problem, dismissed new reports. Locals were left to fend for themselves.

Jean Chastel, who was serving time for refusing to help with previous hunts, was both a skilled marksman and devoutly religious. Allegedly, he finally killed the beast with a silver-tipped bullet and special prayers. The Beast’s head was cut off and stuffed, but it began to rot and was eventually thrown away.

Theories

This was not the first time France had suffered wolf/werewolf hysteria. During the 1500s and 1600s, the French countryside was plagued by disappearances, prompting parliament-sanctioned werewolf hunts. These hunts often targeted social outcasts and loners, and frequently resulted in dubious convictions. These bouts of hysteria often coincided with times of great strife.

A study led by researcher John D. C Linnell suggested that most of the attacks were likely wolves or dogs:

From our point of view, it is impossible to be 100% certain. However, even if some of the cases may have been due to other agents rather than a wolf, historians who have examined the case believe there is a very high chance that a wolf or wolves were involved in many of the deaths.

It is also highly possible that several attacks attributed to wolves could be due to domestic or feral dogs, wolf-dog hybrids, or similar species.

It is also possible that newspapers sensationalized the beast, either to attack the King or to attract readers. The newspaper Courrier d’Avignon published a whopping 98 stories about it.

An illustration referring to the beast as a hyena. Photo: Gallicia Digital Library

There could also be a religious element to the story. Gévaudan was a Protestant region, so when news of the attacks circulated, Catholics believed God was punishing the Protestants for their heretical beliefs.

Another possibility is that the beast was a human serial killer dressed up in animal skins. This would explain why it never attacked livestock. However, there is no hard evidence for this theory.

Conclusion

The most likely explanation is that wolves and dogs were responsible for most attacks. When combined with local superstitions, general discontent, and a period of strife, perhaps the legend of the Beast of Gévaudan was born.