By 1979, the Cold War had dragged on for 32 years. The nuclear ambitions of major world powers were held at bay by a treaty that banned atomic weapon tests in the atmosphere and underwater. Yet, in the wee hours on September 22, satellites picked up an exceedingly bright double flash in the South Atlantic.

Background

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki introduced a new weapon that could decimate life on Earth. For years after, the Cold War and the threat of annihilation hung in the air as countries scrambled for military supremacy.

Displays of power through nuclear tests like those of Castle Bravo or Tsar Bomba were both impressive and terrifying.

The Baker Test. Photo: Shutterstock

The Cold War featured secrecy, espionage, close calls, and intense fear. Thankfully, world leaders pulled back from the brink and placed restrictions on nuclear testing in the hope of curbing nuclear proliferation. In 1963, the United States, the United Kingdom, the USSR, and 100 others signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty.

The U.S. launched the Vela Hotel satellites to ensure that everyone complied with the rules. Their job was to detect nuclear detonations by scanning for x-rays, gamma rays, neutrons, and light. Together with satellites developed by the Defense Support Program (DSP), they scanned for nuclear activity.

The incident

Just before 1 am on Sept. 22, 1979, Vela 6911 detected a double flash, characteristic of a nuclear blast. The initial flash peaked in luminosity before declining with the shock wave. Then, it peaked a second time before declining again, all within a matter of milliseconds. The data determined the explosion was around three kilotons.

The point of origin was within a 5,000-kilometer radius between the Prince Edward and Marion Islands off the coast of South Africa, and the Crozet Islands in the sub-Antarctic, some of the most remote islands in the world. No one lives on these islands, but they sometimes host researchers.

There were no recorded eyewitnesses, and no one claimed responsibility.

Vela satellite illustration.

The situation was puzzling. Vela 6911 was the only satellite to pick up the blast, and though the flash had most of the characteristics of a nuclear blast, it did not possess one crucial marker. There was no nuclear fallout or radioactive debris.

“The DSP satellites recorded no flash, and no radioactive debris was found. [However] a researcher at Arecibo recorded an ionospheric wave traveling in an anomalous direction that could have resulted from a nuclear test,” Leonard Weiss, a researcher in International Security at Stanford University, explained.

The U.S. investigated, but aerial reconnaissance found no sign of fallout. The Naval Research Laboratory analyzed ocean data using hydroacoustic sensors designed to detect sound waves traveling underwater. Though the sensors are particularly important for detecting underwater detonations, they can also capture the acoustic effects of atmospheric nuclear tests if the explosion is powerful enough.

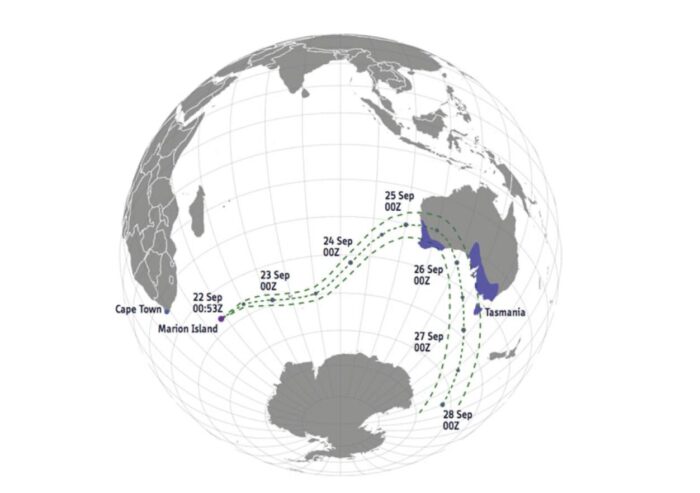

“The most probable test location was above shallow waters close to the remote South African Prince Edward Islands, some 2,200km southeast of Cape Town,” Weiss wrote. “The satellite detection information remained secret for about one month before ABC reported it on Oct. 25, 1979.”

Theories

U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s administration was unpopular. Many Americans thought him weak both domestically and in foreign policy. Carter faced Soviet aggression overseas, tension in the Middle East, an ongoing energy crisis at home, and stagflation of the American economy. His 1980 reelection bid was looking bleak.

Evidence of a nuclear blast panicked Carter and the State Department. They hoped to deal with the issue secretly, but someone leaked it to the press soon after.

“There was indication of a nuclear test explosion in the region of South Africa, either South Africa [or] Israel using a ship at sea…At the foreign affairs breakfast, we went over the nuclear explosion. We still don’t know who did it,” Carter wrote in his diary.

Then in February 1980, he wrote: “We have a growing belief among our scientists that the Israelis did indeed conduct a nuclear test explosion.”

An Israeli test?

Was Israel responsible? The CIA believed that, by 1974, Israel possessed around 20 nuclear weapons.

The most widely accepted theory about the Vela Incident is that Israel and South Africa were co-responsible for the nuclear explosion. During the Cold War, both countries were isolated for different reasons. Israel was concerned about regional security and the Arab-Israel Conflict. South Africa, under apartheid rule, considered nuclear weapons a means of securing its political position on the world stage.

South Africa had been developing its nuclear program in secret since the 1960s. There are eight major uranium deposits in South Africa, and the country made a deal with Israel: they would provide uranium while Israel assisted with research and construction.

Commodore Dieter Gerdhart, a high-ranking official in the South African navy (who was also moonlighting as a Soviet spy), claimed to have witnessed multiple clandestine military exercises between South Africa and Israel. In 1994, he told the Johannesburg City Press that the Vela incident was part of a secret operation between the two countries called Operation Phoenix.

However, experts deemed Gerdhart an unreliable source because he was both a spy and unable to back up his claims with evidence.

Ultimately, no country was blamed for the Vela incident. Carter and other leaders simply turned the other way, hoping the problem would disappear.

Alternative theories

Some classify the Vela Incident as a “zoo event.” A zoo event is a false signal or mimic of a nuclear explosion. Natural phenomena like micrometeoroid impacts or even something as trivial as sunlight reflecting off the satellite can cause zoo events. Micrometeroids are not uncommon, but the probability of them hitting one of the satellites is one in a billion. If it was sunlight, why wasn’t the phenomenon replicated afterward?

In May 1980, Jack Ruina of MIT brought together a team of eight scientists to try and explain the incident.

“We consider the alternative explanation of the September 22 signal as light reflected from debris ejected from the spacecraft as reasonable, but we do not maintain that this particular explanation is necessarily correct,” Runia said.

There is also the possibility that the satellite malfunctioned. Vela satellites had a short shelf life of approximately seven years, and the U.S. launched the DSP satellites to replace them.

In 1967, the Vela satellites documented the world’s first evidence of gamma-ray bursts. Gamma radiation is part of the nuclear explosion process, so perhaps events occurring in deep space were mistaken for a nuclear explosion on Earth.

Vela incident proved by sheep?

There was a breakthrough in the case in 2017. Professor Lester Van Middlesworth found that sheep in southeastern Australia carried the nuclear fallout marker iodine-131, dated just days after the Vela incident.

Van Middlesworth found Iodine-131 in the sheeps’ thyroids. The blast may have been a low-level detonation that did not create enough fallout for a satellite to detect from orbit, but just enough to show up in these sheep.

The possible trajectory for nuclear fallout after the Vela incident. Photo: Lars-Erik De Geer and Christopher M. Wright

By 2003, the U.S. National Security Council was confident enough to state with “high confidence” that the Vela incident was a nuclear explosion.

All these years later, no country has claimed responsibility.