I first encountered the word “Thule” in college while pouring over beyond-old world maps in class. I thought nothing of it for the next few years until I stumbled across the word again, this time in an obscure mythology page on Facebook. Whether it was a happy accident, coincidence or divine intervention, it is a story wanting to be told.

As a mythical place, Thule is less known than its other Greco-Roman counterparts like Atlantis, Hyperborea, or Lemuria. However, that has not stopped it from forever cementing its place in the minds of classical navigators and today’s arctic aficionados.

An accidental discovery

Our voyage begins around 330 BC with a tale of a man who ventured beyond the known world and into a land of frigid cold, strange seas and even stranger people. His name was Pytheas, and he decided to explore beyond his native Massalia (modern-day Marseilles in France).

Pytheas was a scientist, astronomer, and navigator with a unique mission: to search for amber, tin, and gold. Amber was an extremely valuable substance used in medicines, religious practices, jewelry, and most importantly, trade. Tin and gold served many purposes, including weapons. As a Greek colony and trading hub, Massalia served the western Mediterranean, so finding priceless items like these was a priority.

After leaving Massalia, Pytheas sailed through the Pillars of Hercules (Gibraltar) and into the perilous Atlantic to the north, hugging the Atlantic coast of Europe. Then, he discovered a new, cold land with a very rugged coastline measuring over 40,000 stadia (over 7,200km).

This was Britain, and he was the first Greek to set foot on its shores. He was the first Greek to sail to Northern Europe at all. Pytheas took the opportunity to traverse the land itself on foot, witnessing the tin mining activities of the natives on the Cornish coast and traveled as far as the Orkney Islands. After Britain, he continued north for six days, looking for more of these lands. Little did he know that things would take a strange turn. He says:

Neither earth, water, nor air exist separately, but are a sort of concretion of all these, resembling a sea-lung in which the earth, the sea, and all things were suspended…

…there are no nights during the solstice when the sun is passing through the sign of Cancer and also no days during the winter solstice…

‘Congealed’ sea

For someone from the Mediterranean, this was a never-before-seen, alien phenomenon. Not only was the sea “congealed”, but it was immensely cold and full of mist. However, when he came out of the fogbank, he saw it was a land of “endless splendor” as he further observed that the sun hung in the sky perpetually.

The people who lived there were very tall, strong, pale, blond-haired, and wise. They survived on fish, possibly seals, herbs, fruits, and millet and even had a popular drink made of grain and honey. They had technologies like tools and boats.

After this groundbreaking discovery and subsequent expeditions by Greeks and Romans alike, the land became known on maps as “Thule,” meaning beyond the borders of the known world. The Romans took it a step further by calling it Ultima Thule, which further exaggerated its remoteness.

There is a lot to unpack here and lots of substantial clues as to where this mysterious island could be. Pytheas originally documented his voyage in a work called On the Ocean. However, it is long gone. It fell victim to the fires that engulfed the Library of Alexandria. His writings are forever lost, so we would have to settle with the bits and pieces found scattered in the works of his contemporaries and writers thereafter. This became a problem.

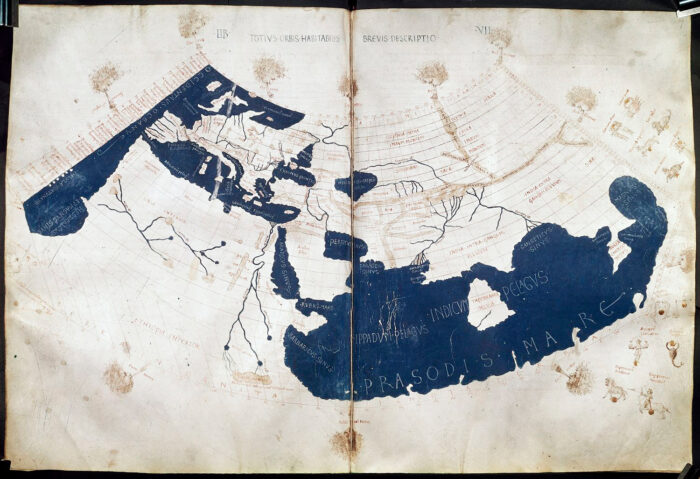

Thule on Ptolemy’s world map. Photo: Ptolemy

A ‘falsifier’?

Not everyone in the classical world believed Pytheas found an idyllic northernmost land. Some contemporaries who relayed Pytheas’s story just didn’t buy it. In fact, they conveyed outright hostility and defamed Pytheas as a “falsifier” and opportunist. His main critics, Strabo and Polybius, did not believe that Pytheas even went to Britain. In a commentary from Strabo, he says:

Pytheas, by whom many have been misled; for after asserting that he traveled over the whole of Britain that was accessible, Pytheas reported that the coastline of the island was more than forty thousand stadia, and added his story about Thule…

…For not only has the man who tells about Thule, Pytheas, been found, upon scrutiny, to be an arch-falsifier, but the men who have been to Britain and lerne [Ireland] do not mention Thule. . . . However, any man who has told such great falsehoods about the known regions would hardly, I imagine, be able to tell the truth about places that are not known to anybody…

‘Impossible,’ said critics

Strabo refused to acknowledge that such a sea existed, let alone a people who could grow food in such a climate. Polybius believed Pytheas made geographical errors and that sailing along the northern European coastline was virtually impossible. This is most likely because no one ever thought a Greek could reach so far.

But despite the controversy, Thule was a reality. In the 2nd century AD, Dionysus visited Thule and experienced the same perpetual sunlight that Pytheas had described. Roman figures seemed to be more forgiving than the Greeks, further bolstering Pytheas’s claims.

The Roman historian Tacitus (56–120 AD) mentioned Thule in his work Germania, where he describes it as a land of great cold and darkness beyond the reach of Roman authority. He said the crew sighted it somewhere beyond the Orkney Islands.

In Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, he catalogs Thule as lying six days north of Britain and a land of “no nights at all.” In the 3rd century AD, historian Gaius Julius Solinus stated that Thule was “fruitful and abundant in the lasting yield of its crops.” After him came Servius in the fourth century, who said Thule was just after the Orkney Islands. Roman poets Claudius and Celius Cetalicus spoke about its strange inhabitants being painted blue. The poet Virgil famously stated:

There will come an epoch late in time when Ocean will loosen the bonds of the world and the earth lie open in its vastness, when Tethys will disclose new worlds and Thule not be the farthest of lands.

The list goes on, and Thule had its place in the world. It even became interchangeable with the very similar myth of Hyperborea. The question that remained was, where exactly is it?

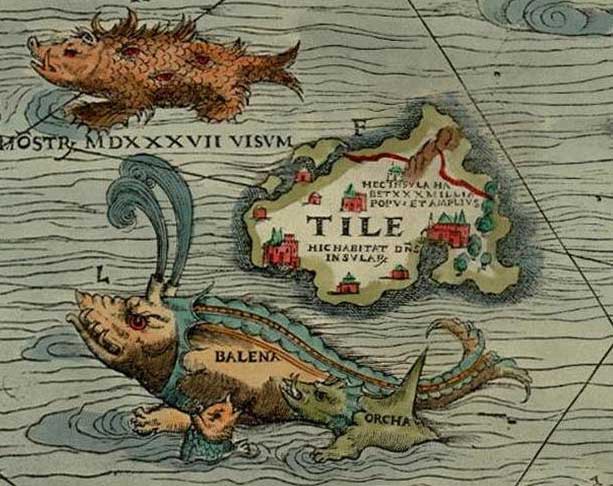

Thule in the Carta Marina. Photo: Olaus Magnus

Theories

In later centuries, especially during the Middle Ages, Thule became only a symbol of the unknown north. Some scholars believe Pytheas may have been referring to Iceland, given the description of a land north of Britain that experiences long summer days. Others suggest that Thule could refer to Scandinavia in general. Our biggest clue is that the land has no nights, which narrows us down to Norway, Sweden, and Iceland.

The “congealed sea” resembling a “sea-lung” also gives us an idea. A sea-lung was an ancient term for jellyfish. A type of substance that looks like a jellyfish would be either new sea ice or pumice. Both exist in the Arctic Circle near Iceland, with its many volcanoes.

Classicist H.J.W. Wijsman at the University of Amsterdam suggested that Thule was the Shetland Islands, which lie halfway between Orkney and Norway. They experience long days of sunlight and pancake ice. However, the Shetlands are too close to Britain to be six days north. Six days suggests either Norway or Iceland.

That should solve it, right? Wrong. There’s another piece to the puzzle: the inhabitants.

Slain Scots

In his writings, the poet Claudius said:

Thule was warm with the blood of Picts; ice-bound Hibernia [Ireland] wept for the heaps of slain Scots.

This detail has made many believe that Thule was actually Scotland since the Picts were its native inhabitants. Celius Cetalicus claimed the natives were painted blue, which the Picts infamously did. We do not know much about what eventually happened to the Picts. They seemed to have vanished completely except for a few archaeological remnants here and there.

Historians do not even know their origin story. Did the Picts originate from Thule and migrate to the British Isles? A clue from Eustathius of Thessalonica could help. He wrote that the inhabitants of Thule were at war with dwarves living in the inner earth. Therefore, they had to flee to nearby lands in the region. This oral tradition continued in the writings of another scholar, Geoffrey of Monmouth, who suggested that dwarves invaded the British Isles in the distant past.

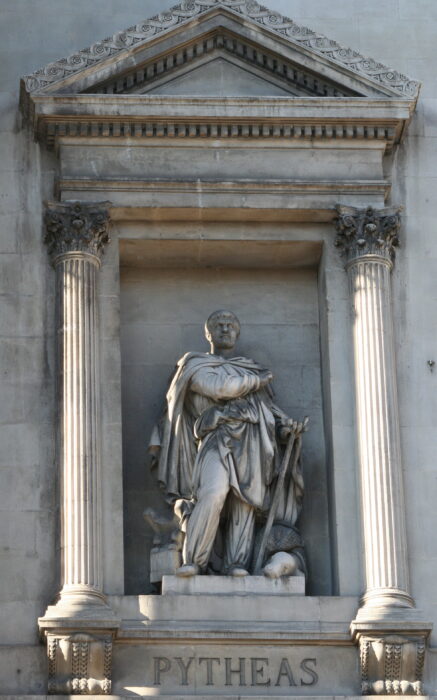

Pytheas in Marseille. Photo: Rvalette/Wikimedia Commons

Some offer a more straightforward hypothesis than a dwarf invasion from the center of the Earth. Because Thule seems likely to have been either Scandinavia or Iceland, the blond-haired, tall inhabitants might be Vikings. A Byzantine Greek princess and historian named Anna Komnene explicitly wrote that the Vikings came from Thule. They seem to fit the descriptions, and the Vikings were seafarers, after all. This brings us to our next chapter in the story: the island of Smøla.

Smøla

At first glance, there isn’t much here. The Norwegian island of Smøla has a population of just over 2,000 people and a handful of modest wooden houses surrounded by frigid waters. But tourism is bustling since it is being marketed as the lost island of Thule.

In a study done by the Technical University of Berlin, researchers used ancient Greek and Roman maps to determine Thule’s location. Taking into account the ancient world’s tendency to over or under-estimate distances, they somehow managed to zero in on this small island. One of the researchers told a local Smøla journalist:

About this old information, there cannot be an doubt anymore…You live on the mystic island of Thule.

Local politicians and leaders in the community agreed.

Aerial view of Smøla. Photo: fogcatcher/Shutterstock

A dubious symbol

Thule became an important symbol for explorers and even some evil characters. Thule played a central role in Nazi Germany’s occultist beliefs. During the early 20th century, a group of German occultists and nationalists formed the Thule Society. It believed that Thule was a lost homeland of the Aryan race. The society was influential in the early stages of the Nazi Party. Although it did not find any physical evidence of Thule, its name became associated with esoteric ideas and racial myths.

Modern scientific expeditions, such as those focusing on Greenland and the Arctic Ocean, continue to push the boundaries of our understanding of the Earth’s polar regions. The Thule Air Base in Greenland (now officially called the Pituffik Space Base), operated by the United States Air Force, is a symbol of the real-world presence of human activity in the remote Arctic, once thought to be beyond civilization’s reach.

Thule Air Base, Greenland. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Its name carried on to places like Thule Island in the South Sandwich Islands and the Thule people (ancestors of the modern Inuit). However, they have nothing to do with the actual myth.

One thing is certain: more attention must be paid to the inhabitants, particularly the Picts. There is a clear gap in their story and the very random mention of them by Roman scholars. If the Picts originated from Thule, this would unlock a vital part of Scottish history that we did not know existed.