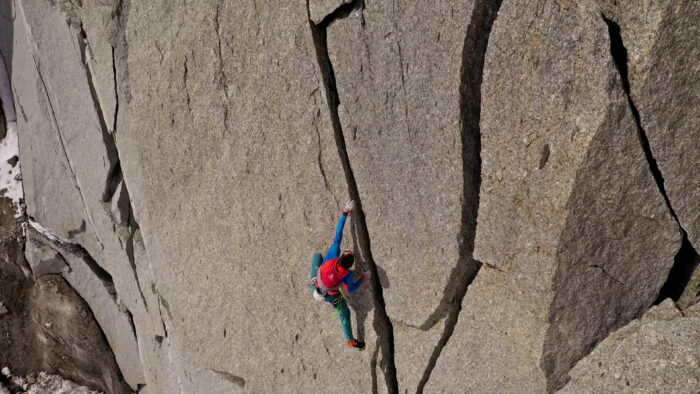

Grand Capucin in 49 minutes. Aiguille Noire de Peuterey in just over an hour and a half. The north ridge of Piz Badile in 42 minutes and 52 seconds. Linking the four ridges of the Matterhorn in 7 hours, 43 minutes, and 45 seconds.

This brief list of exploits — perhaps accompanied by Pat Boone’s song dedicated to Mexico’s fastest mouse — captures the career of Poland’s Filip Babicz, a competitive climber and alpinist who has been living at the foot of Mont Blanc for years.

I spoke to Babicz recently at a mountaineer’s gathering near my hometown in northern Italy. We started at the beginning, discussing the child whose father dragged him in the late 1980s to the Tatra Mountains.

Filip Babicz with his father in the Tatra Mountains, 1995. Photo: Filip Babicz

From comp to speed

“My father is a guide in that area, so I learned about the mountains by osmosis,” Babicz says. “My greatest passion at the time was practicing any kind of sport with a competitive component.”

He played everything from ping pong, “which I loved and was actually quite good at,” to soccer, “but as a goalkeeper, not a goal scorer.”

At 14, Babicz discovered sport climbing, taking it more seriously than his Sunday mountain outings.

“It seems funny,” Babicz says, “but within a few months I had already decided that was what I wanted to do with my life. It was a brilliant way to combine my sporting streak with the vertical world I had learned from my father.”

Babicz at a World Cup race during his competition career. Photo: Filip Babicz

For 18 years, sport climbing was the center of his life. He competed first for the Polish and then for the Italian national team.

“I moved to Courmayeur at the turn of the millennium, specifically to practice high-level climbing,” he told ExplorersWeb. “I focused more on dry training and sessions at the gym, at most on the crag, which greatly curbed my desire to go to the mountains.”

But then came the turning point. In 2015, while Babicz was preparing for the World Cup, he severely injured a finger, which compromised his competitive season.

“It was a nightmare,” he recalled. “I decided to compete anyway, with my injured finger, but it was terribly painful. The first race went badly, and I felt obsessed with it, desperate at the prospect of having to sit out months. However, once I returned to the Aosta Valley and digested the disappointment, I realized I felt super trained and in good shape, except for my finger, of course. I told myself that rather than stay on the couch, I’d find a plan B in the mountains.”

Filip Babicz on the Grand Capucin. Photo: Vittorio Maggioni

At ease in the Alps

There’s certainly no shortage of mountains in Courmayeur.

“The Alps are the place where I feel most at ease,” Babicz explains. “Mont Blanc and the Aosta Valley are an incredible playground, where you can do anything at any time of day, whenever you want. By comparison, I’ve been to Huaraz, Peru, and if you want to find a decent crag there, you have to drive three and a half hours. Within a 10-minute radius of my house, I can find 10 crags. If I wanted, I could be under the Grand Capucin in less than two hours, without running. There’s no comparison.”

Babicz can only say all this now, after falling in love with the mountains again, thanks to that injury.

“And thanks to Kilian Jornet,” Babicz added. “He was the one I thought about constantly in 2015, during my first ascent of the Matterhorn, which I tackled at a brisk pace. I didn’t want to beat his record, but his performance made me dream.”

One week later, he went to the Gran Becca and took 5 hours and 1 minute to complete the climb, there and back.

“This feat sparked my passion for speed in the mountains,’ he says. “I rediscovered myself. For years, I had thought that only competition existed, but that wasn’t the case.”

Filip Babicz climbing the Grand Capucin. Photo: Vittorio Maggioni

Some detractors might think that speed mountaineering is nothing more than a competition of a different sort.

“That’s right,” Babicz agrees, “and I’m not ashamed to call myself an athlete before a mountaineer. However, my thirst for speed doesn’t clash with ethics.”

He says he prefers free climbing a pitch to hanging off aid.

“I practice drytooling, deep-water soloing, and highballing,” says Babicz. “All of these disciplines have made me realize that my main interest goes beyond the record itself. For example, when opening new routes, I don’t think about chipping holds, not even in drytooling, where everyone at a high level seems to do it.

“This is how the ‘Underground Temple’ in La Thuile was born. There, in a chalk cave, I’ve established the world’s most difficult routes using only natural holds. I’m not looking for the record at all costs. What interests me is achieving it in an exemplary style.”

Babicz in the chalk cave of La Thuile. Photo: Xavier Guidetti

No attraction to the 8,000’ers

While Poland is home to great Himalayan mountaineers, from Jerzy Kukuczka to Krzysztof Wielicki, Babicz does not seem particularly interested in the highest peaks.

“I approached that world in 2019, with the Polish Winter Himalaya (PHZ) program created by the Polish Alpine Club,” he recalled. “The goal was [a] winter ascent of the last remaining 8,000’er unclimbed in winter — K2. I did two preparatory expeditions with the program, one in the Karakorum and the other in the Himalaya”

However, when the Nepalese did their K2 winter climb in 2021, the program ceased to exist.

“It became Polish Sport Himalaya (PHS),” says Babicz. “Its members are, on average, much younger climbers aiming for lower, technically difficult peaks between 6,000 and 7,000m.”

Babicz in the Karakorum. Photo: Marco Schwidergall

“I continue to be part of it,” Babicz continued. “I like the group dynamics and the mutual inspiration, but I prefer mountaineering in the Alps because I feel like an athlete. In the Alps, I’m more likely to take my performance to a very high level.

“And since the vast majority of mountaineers live around here, I consider it a great mountaineering laboratory, where you can push your limits in impressive ways. You can do it in the Himalaya too, but luck plays a decisive role there. It is more manageable in the Alps. I know it’s an unpopular opinion, but if I had to choose between climbing an unclimbed 6,000m peak in Pakistan or beating Ueli Steck’s record on the Eiger by just 30 seconds, there’s no question: I’d choose the Eiger.”

Babicz at the top of Piz Badile after his record. Photo: Vittorio Scartazzini

The mountains of dreams

However, Babicz’s favorite mountains aren’t just in the Alps.

“The peaks that have impressed me most, perhaps, are in Patagonia,” he explains. “From what I’ve seen, they’re the most beautiful in the world. Cerro Torre seems to be from another planet.”

The problem there, he admits, is the weather, which makes any experience more of an adventure than a performance. Rather than attempt to squeeze in something during two small windows within a month of poor weather, he wants to spend an entire southern summer there.

“Winter in the Alps interests me less,” he admits. “I’d like to spend that time [in Patagonia] as a sort of training camp…When a good window opens — if it opens — I’ll try something.”

On the lower part of Horli Ridge. Photo: Vittorio Maggioni

For Babicz, it’s all about open-mindedness and perseverance.

“Things don’t always go according to plan…It’s been like this from the beginning, with that finger injury that ended my career, and immediately made me start a new one.”