Our Forgotten 7,000’ers series moves today from Nepal to Pakistan, which has 76 peaks (including sub-peaks) between 7,000 and 7,999m. Some of these haven’t been climbed for years.

Kunyang Chhish is one of the most complex giants of the Hispar Muztagh. Most of the few expeditions that attempted the 7,852m peak suffered fatalities. Successfully climbed only twice, Kunyang Chhish ranks as the 21st highest independent peak in the world. Below, its climbing history.

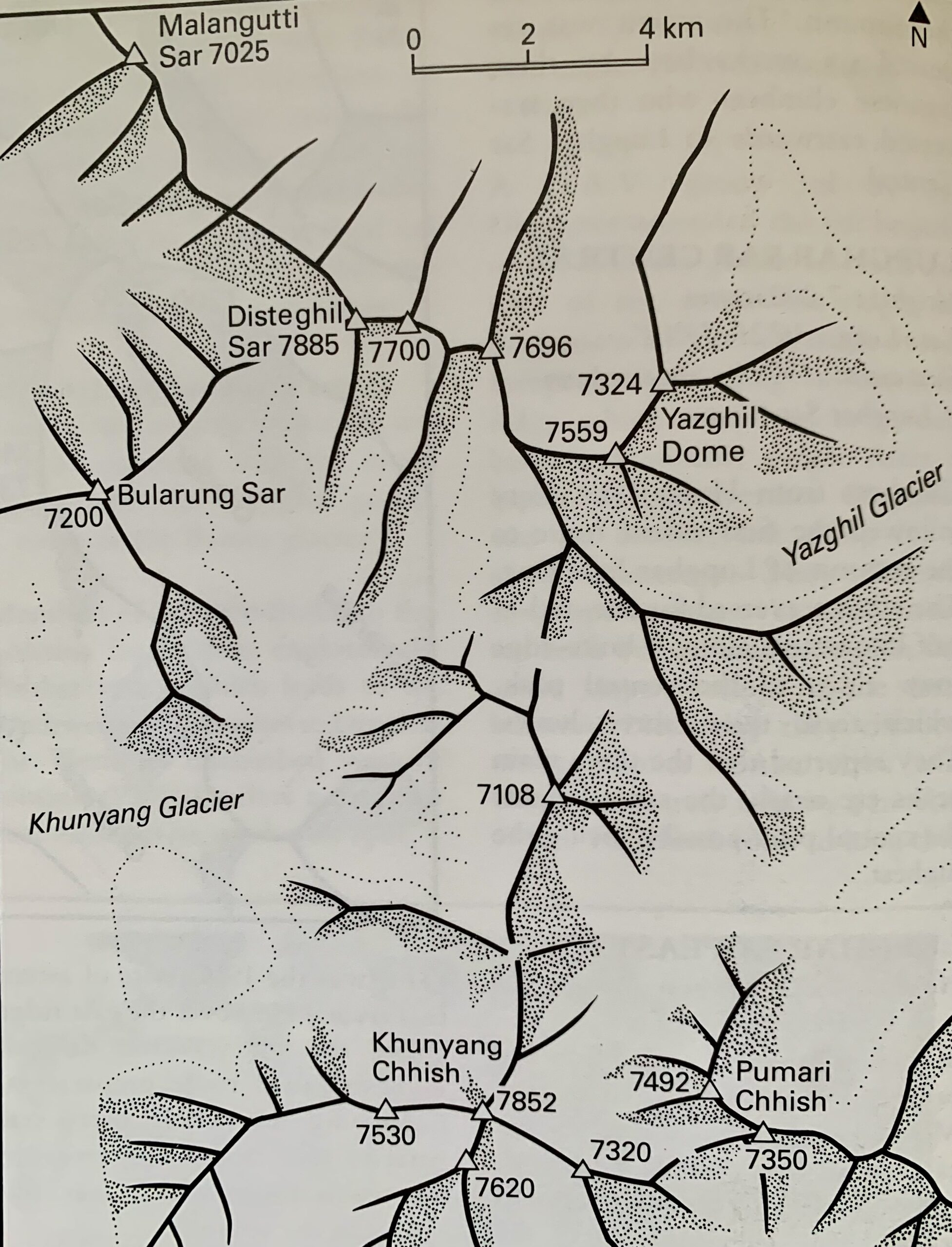

The peaks and some of the glaciers in the area. Photo: Jill Neate

Kunyang Chhish (also written as Khunyang Chhish) is the second-highest peak of Hispar Muztagh, a major subrange of the Karakoram, and the third-highest 7,000’er in Pakistan. Locals call it Corner Peak.

It rises north of the Hispar Glacier and on the southwest side of the Kunyang Glacier. The slightly higher 7,885m Disteghil Sar dominates the Kunyang Glacier on its northern end. Disteghil Sar has a rounded profile, while Kunyang Chhish is much sharper and more difficult to climb. Kunyang Chhish rises almost 4,000m above its southern base camp on the Kunyang Glacier and 5,500m above the Hunza Valley.

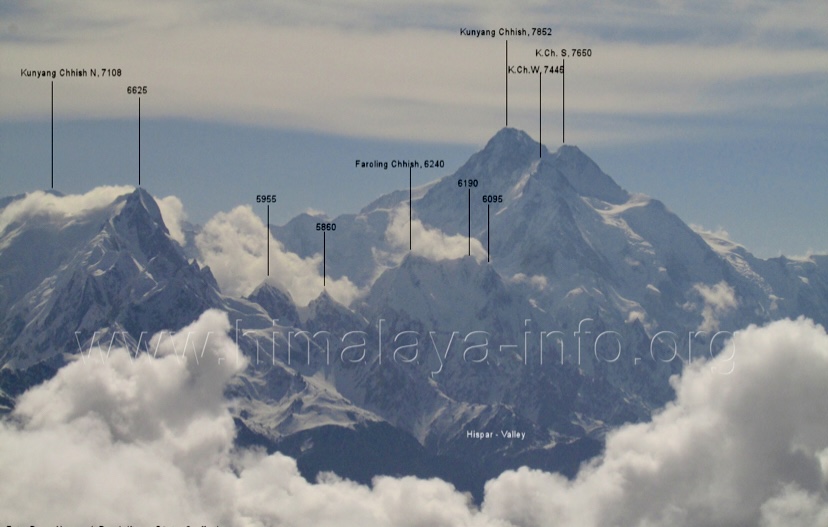

Kunyang Chhish, Disteghil Sar, and Kunyang Chhish North. Photo: Google Earth

The Kunyang Chhish massif has a lower southern sub-summit called Kunyang Chhish South (7,620m) and two subpeaks — 7,400m Kunyang Chhish East and the unclimbed 7,350m Kunyang Chhish West (also called Pyramid Peak).

Kunyang Chhish North (7,108m) is considered an independent peak.

Hispar Muztagh

The Hispar Muztagh subrange extends from the Hunza River gorge, north of the Hispar Glacier, to the head of the Biafo Glacier.

The Hispar Glacier was discovered in 1861 by H. H. Godwin Austen during his explorations. He was the first to ascend most of the glaciers in the area. In 1892, Martin Conway and his partners mapped the Hispar and Biafo Glaciers and made the first crossing of Hispar Pass. Conway was the first to mention Kunyang Chhish in his writings.

Photo: Himalaya-info-org

Fanny Bullock Workman and her husband, William Hunter Workman, went there in 1908 and published a photo of Kunyang Chhish afterward.

In 1938, Michael Vyvyan became the first Westerner to explore the Kunyang Glacier. During that expedition, he approached Disteghil Sar, Kunyang Chhish, and Pumari Chhish.

A year later, in 1939, two members of Eric Shipton’s survey party crossed the col at the head of the Kunyang Glacier but had to abandon any attempt to reach the final col because of avalanche danger.

Kunyang Chhish. Photo: Rizwan Saddique

First attempts

Before its first ascent in 1971, Kunyang Chhish had been attempted twice in the 1960s. Both expeditions ended in tragedy.

In the summer of 1962, Major E. James E. Mills and Captain Jawed Akhter led the British-Pakistani Karakoram Expedition. The party overcame the greatest obstacles on their route up the southeastern side of the mountain, above the Hispar Glacier.

According to the American Alpine Journal, on July 18, Major Mills and Captain M. R. F. Jones were preparing the route along a snowy ridge at about 6,100m when an avalanche fatally swept them 1,525m down to the Pumari Chhish Glacier. After the accident, the expedition called off any further attempts.

Kunyang Chhish (center background), and Pumari Chhish (left background) as seen from Yazghil Sar’s western slopes. Photo: Yousef Al-Nassar

The second fatal attempt

In the summer of 1965, a Japanese expedition from the Tokyo University Alpine Ski Club, led by Hirotsugi Shiraki, went to Kunyang Chhish. The party included 13 Japanese from the club and Mohammed Asif of Pakistan, whose climbing (and language) skills helped them greatly. The reconnaissance party left Nagar on June 18 and spent five days on the Kunyang Glacier, trying in vain to find a route to the summit from the western side of the mountain.

On June 27, the Japanese established Base Camp at 3,887m, beside the Hispar Glacier and at the foot of the south ridge, which the 1962 expedition had also tried.

Shiraki’s party established Camp 1 on the spur at 4,800m, Camp 2 at 5,303m where the spur meets the southeast ridge, and Camp 3 beyond the junction of the southeast and southwest ridges, shortly before a vertical rock tower.

Kunyang Chhish from the northeast. Photo: Yousef Al-Nassar

On July 17, the climbers set up Camp 4 on the so-called Snow Dome at 5,898m. Here, the Japanese had to spend nine days due to a snowstorm from July 28 to August 7. After it passed, they resumed and established Camp 5 at 6,924m and Camp 6 at 6,904m. They then set up Camp 7 at 7,010m, just below Rock Peak.

Two more subpeaks, Triangle Peak (7,400m) and Tent Peak (7,696m), still separated them from the summit of Kunyang Chhish. According to Shiraki, difficult rock, ice walls, and knife-edged ridges with complicated cornices and crevasses ran all the way from Camp 2 to Camp 8 and forced them to use all the rope they had.

Tragedy strikes

On August 19, five climbers set off for Camp 8, just a day from the summit. On their way, at 7,193m, a narrow snow ridge suddenly collapsed, and Takeo Nakamura fell all the way down to the Kunyang Glacier. The rest of the Japanese party rushed back to Base Camp to search for his body, but it had disappeared. The grieving expedition abandoned Base Camp on August 27.

Andrzej Zawada during the 1971 Kunyang Chhish expedition. Photo: Andrzej Zawada

The Poles discover Asia

In 1939, the Poles went to the Himalaya for the first time and climbed Nanda Devi East. After that expedition, World War II made it impossible for them to return to Asia for several years.

In 1966, French climbers wanted to organize a joint French-Polish expedition to the Hindu Kush. Andrzej Zawada persuaded them to try a more ambitious climb, but after all the preparations were complete, the French withdrew. However, in 1966, the authorities approved a Polish national team expedition to the Karakoram. In the autumn of 1966, Ryszard Szafirski led a reconnaissance that made the first ascent of 6,843m Malubiting North.

In 1971, Zawada returned with a team to attempt Kunyang Chhish.

The charismatic Andrzej Zawada had a great influence on his climbing partners. His Kunyang Chhish expedition would kick-start an outstanding career, as well as begin the Polish era in high-altitude mountaineering.

Zawada chose a different route up Kunyang Chhish than the two previous attempts. He conceived a much shorter line through technically difficult and exposed terrain. They would go directly up from the Pumari Chhish Glacier via the southeastern wall to the south ridge, and then onto the summit.

Their line, though shorter than the Japanese route of 1965, was much riskier and required fixed ropes.

Left to right, Szafirski, Stryczynski, Zawada, and Heinrich. Photo: Andrzej Zawada

The climbers included Zawada, Eugeniusz Chrobak, Krzysztof Cielecki, Jan Franczuk, Zyga Heinrich, Bogdan Jankowski, Andrzej Kus, Jerzy Michalski, Jacek Poreba, Ryszard Szafirski, J. Stryczynski, and Stanislaw Zierhoffer (the doctor and deputy leader).

A long drive

On May 15, 1971, Michalski, Heinrich, Poreba, and Zierhoffer set out in a Star A-29 truck from Warsaw to Pakistan with six tonnes of equipment. They reached Islamabad three weeks later, on June 8. The other members of the expedition arrived in Pakistan later.

By truck to Pakistan. Photo: Andrzej Zawada

The party established Base Camp on the Pumari Chhish Glacier on July 2. Before starting the climb, they somberly wrote letters to their families, just in case. Their planned route was full of avalanches, even on the lower sections.

They carefully observed the timing of the avalanches and made an “avalanche schedule” to avoid them. But the slides were so frequent that sometimes, the only way the climbers could avoid being swept away was to run madly out of the slide’s path. This way, they reached Camp 1.

On July 24, Heinrich and Szafirski set up Camp 2 at 6,500m. Between July 25 and 27, the climbers fixed ropes up the difficult Ice Cake ridge. At 6,450m, under what they called the Ramp, they set up Camp 3. The next day, tragedy struck.

Base Camp. Photo: Andrzej Zawada

On July 28, 10m above Camp 3, the youngest member of the expedition, 26-year-old Jan Franczuk, was about to attach himself to the rope when a large chunk of snow broke off and pushed him into a crevasse. He was then buried in the snow. The next day, one of the climbers made a dramatic radio report to Base Camp:

”We don’t know exactly where and how deep [Franczuk is buried]. We [will] dig until evening…Wait, sorry…Listen…hey…can you hear me? Janek has found him. [He] dug him up. He [Franczuk] is dead.”

Jan Franczuk. Photo: Portalgorski.pl

Stay or go?

After Franczuk’s death, the climbers returned to Base Camp and discussed whether to continue or go home. One faction of the Polish team wanted to abort, but another -– Zawada among them — argued for continuing. They stressed that they wanted to summit in part as a homage to Franczuk. In the end, the team agreed to continue.

Funeral ceremony on the mountain for Jan Franczuk. Photo: Abdrzej Zawada

During the first week of August, they began climbing again, and on August 8, Heinrich and Szafirski set up Camp 4 at 7,200m on a narrow ridge under a col. But five days later, bad weather forced them all to return to Base Camp. The storm lasted nine days, then they resumed climbing on August 25.

Camp 2. Photo: Andrzej Zawada

Zawada, Heinrich, Stryczynski, and Szafirski hurried up to 7,780m, where they bivouacked in great discomfort below the summit. The support team stayed at Camp 2, at 6,500m.

The next day, August 26, at 7:45 am, Zawada, Heinrich, Stryczynski, and Szafirski topped out on Kunyang Chhish’s main summit. There, they paid tribute to Franczuk and started their descent at 10 am. The four climbers made one bivy between Camps 4 and 3 before descending all the way down to base camp.

Andrzej Zawada on the summit of Kunyang Chhish. Photo: Andrzej Zawada

“Summiting Kunyang Chhish was more meaningful than even the winter Everest ascent,” wrote Zawada later. “It’s an enormous mountain; you can hide the entire Polish Tatra mountains in one Kunyang Chhish.”

The Kunyang Chhish expedition marked the rebirth of Polish mountaineering after the Second World War.

Heinrich, Stryczynski ,and Szafirski on the summit. Photo: Andrzej Zawada

The second ascent

The second ascent of the main summit took place in the summer of 1988. On July 11, two British climbers, Mark Lowe and Keith Milne, members of an expedition led by Andrew Wingfield, summited via the Northwest Spur-North Ridge.

On a Japanese expedition in 1987, one member, Takumi Onuma, fell and died after a falling block of ice cut his rope.

Only six people have summited Kunyang Chhish, and five climbers have died. This mountain has one of the highest fatality rates in the Karakoram.

The first ascent route on Kunyang Chhish East, in 2013. Photo: Hansjorg Auer

A few other expeditions have attempted Kunyang Chhish. Among them, Kazuo Tobita of Japan made six attempts on the peak between 1995 and 2003. Tobita met Zawada at K2 Base Camp when he led the 1985 Japanese expedition. Since that meeting, he dreamed of climbing Kunyang Chhish one day.

In 1979, eight members of a Japanese expedition from Hokkaido University made the first ascent of Kunyang Chhish North.

An Austrian party first ascended Kunyang Chhish East in July 2013 via the south wall.

A memorial to Jan Franczuk at Kunyang Chhish’s base camp, built by his partners in 1971. Photo: Andrzej Zawada

You can find more photos and videos of the Polish expedition on the Andrzej Zawada Museum website.

The short documentary below features original radio conversations and videos (with English subtitles) from that landmark 1971 Polish expedition.