In the early 20th century, climbers faced the constant challenge of how to keep their footing on everything from rocky slabs to icy slopes. Two key innovations, the Tricouni nails and the modern crampons, emerged as solutions. Each had its strengths and limitations. Preferences evolved gradually, driven by use, technological advances, and shifting tastes.

Long before the 20th century, mountaineers used nailed boots. These developed from the simple hobnailed designs used by hunters and travelers. The boots featured metal studs hammered into leather soles to improve grip on slippery or uneven ground.

By the late 19th century, as winter climbing gained popularity in the Scottish Highlands and the Alps, nailed boots became essential. According to mountaineering historian Alex Roddie, in his excellent 2016 article Pilgrim’s Progress: a century of development in climbing equipment and technique, early nails like clinkers (square-headed studs hammered through the sole) offered durability but weren’t replaceable once worn down. This led to frequent slips on ice or smooth rock.

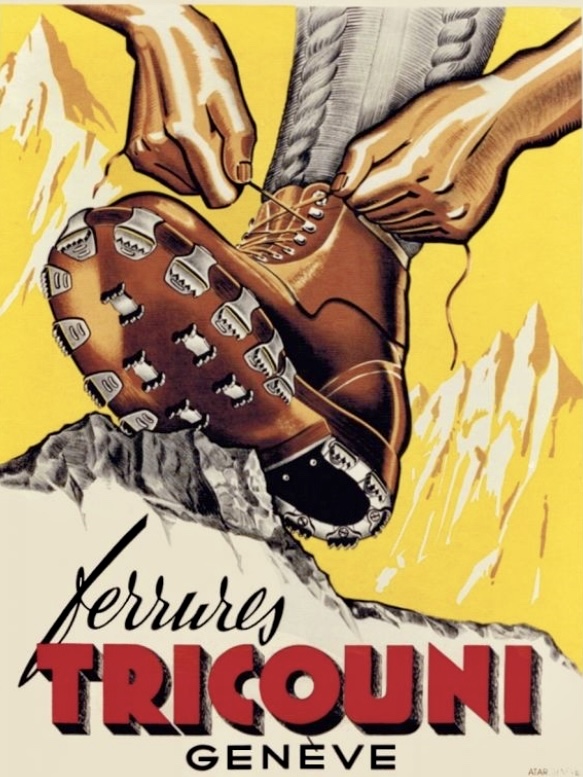

A poster from 1930. Photo: Atar Printing House, Geneva, via memoiredeveyrier.ch

Breakthrough

The breakthrough came at the turn of the century with the invention of the Tricouni nail by Felix-Valentin Genecand. This Geneva-based jeweler and passionate climber was nicknamed Tricouni after a climb near his home. Genecand began his designs in the late 1890s, and by the early 1910s, the finalized Tricouni had become the industry standard.

Genecand’s design featured a hardened steel edge soldered to a softer body, with serrated edges for superior bite. These nails attached to the boot sole using two staples, making them more secure and easier to replace than traditional hobnails. This innovation quickly became popular among alpinists for its versatility on mixed terrain.

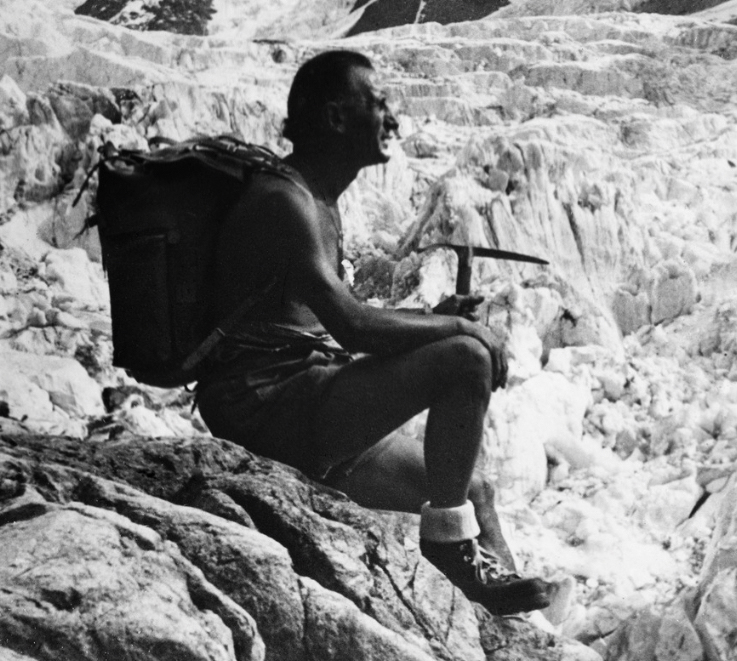

Felix-Valentin Genecand. Photo: Genecand Family Archive via memoiredeveyrier.ch

Tricouni nails allowed climbers to tackle moderate winter routes without additional gear, as they provided an “incontestable” hold on rock. They also performed well on snow, according to Gaston Rebuffat‘s 1963 guide On Snow and Rock, as noted by Roddie.

However, they weren’t without flaws. Nailed boots, including those with Tricouni patterns, were heavy, noisy, and prone to damaging delicate rock surfaces. In a 1920 account from Harold Raeburn’s Mountaineering Art, climbers were warned to “look with suspicion upon the climber who says he wears the same pair of boots without re-soling for three or four years,” as worn nails could endanger a party on serious terrain.

Despite these issues, Tricouni nails dominated throughout the 1920s and 1930s. While a full professional fitting was relatively expensive, they became the standard for reliable, all-purpose traction.

Prehistoric claims, and skeptical reality

While the roots of modern crampons trace reliably back to the 16th century (when European hunters used simple four-point grappettes for snow travel), some earlier claims pushed the timeline much further into prehistory.

In the early 20th century, archaeologists occasionally interpreted certain Iron Age artifacts from Austria’s Hallstatt culture as evidence of ancient climbing crampons. These included a simple iron bar with three conical points and pierced lateral uprights, and a bronze unit featuring multiple prongs and curved supports, both found in local graves.

Hallstatt, Austria, marked on the map. Photo: Britannica.com

In the mountaineering literature of the day, figures like Lord Conway suggested crampons were a Celtic invention later carried across Europe. However, a 1934 note in the American Alpine Journal by J.M.T. (likely James Monroe Thorington, a prominent AAJ contributor and mountaineering historian at the time) cast doubt on this romantic notion.

The author pointed out practical problems: The objects would have been awkward and insecure to attach to the foot, and the Austrian grave examples showed no signs of the wear you’d expect from repeated use. They also represented a costly use of valuable metal when simple wooden cleats would have done just as well. The second pair, found alongside horse equipment, was more convincingly identified by expert Oliver Eaton Cromwell as primitive stirrups rather than foot irons for climbing.

In the end, the piece gently debunked the prehistoric crampon myth, reinforcing that true crampons emerged much later. This aligns with the gradual, evidence-based evolution from nailed boots to dedicated ice traction tools that defined alpinism in the 20th century. It also shows how easily enthusiasm for ancient ingenuity can sometimes outpace the archaeological facts.

Oscar Eckenstein

By the late 19th century, the use of early rudimentary crampons had waned among serious mountaineers, who favored nailed boots and labor-intensive step-cutting with ice axes. This changed in 1908 when British engineer and climber Oscar Eckenstein designed the first modern 10-point crampon, motivated by the inefficiencies of step-cutting, which demanded huge stamina and exposed climbers to hazards like avalanches.

Crampons in the early 20th century. No front points but otherwise familiar. Photo: Grivel.com

Eckenstein collaborated with Italian blacksmith Henry Grivel to produce a lightweight, strong steel frame that fit snugly on boots, featuring long, sharp points. As Roddie explains, this allowed climbers to walk up steep ice by turning their ankles to engage multiple points, drastically reducing the need for cutting steps.

The design went commercial in 1910, but adoption was slow. Many British alpinists remained skeptical, viewing crampons as a crutch compared to the “pure” technique of nailed boots and axes. Eckenstein himself reflected on the potential in 1908: “What the ice climbers of the future will be able to climb, I know not. But I find it hard to believe that we have already reached the limits of what is possible.”

Refinements followed. In 1929, Laurent Grivel added two front points to create the 12-point crampon, enabling steeper ascents. By 1933, chrome-molybdenum steel improved durability. A pivotal moment came during the 1938 first ascent of the Eiger’s North Face, where Germans Anderl Heckmair and Ludwig Vorg, equipped with 12-point crampons, overtook Austrians Heinrich Harrer and Fritz Kasparek— who relied on hobnailed boots and 10-point crampons, respectively — and the group summited together.

Using crampons while remaining elegant. Photo: Grivel.com

Comparisons

In practice, Tricouni nails and crampons complemented rather than competed. Nailed boots shone on mixed or rocky ground, offering “always-on” grip without the need to carry or attach extra equipment. As the American Alpine Club notes, they provided traction on varied surfaces but struggled on hard, continuous ice, where spikes could dull or fail to penetrate.

Detachable crampons were ideal for glaciers and steep frozen slopes, with their longer points biting deeply for secure footing.

Drawbacks for both emerged in real-world use. Nailed boots required meticulous maintenance (oiling leather to prevent cracking and replacing worn nails), and could lead to “nail-sick soles” riddled with holes. Crampons, strapped with hemp or leather, were cumbersome to adjust and added weight when not in use.

Gaston Rebuffat captured the nuance in On Snow and Rock: “On rock, their hold [Vibram soles] is incontestable; on snow, they hold as well as Tricounis; on ice, Tricounis are preferable, but if the ice is really hard, it is in any case necessary to put on crampons,” as noted by Roddie.

Expedition reports show hybrid use: Climbers wore Tricouni-nailed boots for approaches and added crampons for icy sections, illustrating a pragmatic blend rather than rivalry.

Vibram soles, 1937. Photo: eu.vibram.com

Rubber soles

The mid-20th century marked a turning point with the introduction of Vibram rubber soles in 1937 by Italian climber Vitale Bramani. These gave superior friction on rock (better than nails) while remaining flexible for snow. Combined with detachable crampons, they had rendered permanent nailing obsolete by the 1950s and 1960s. Roddie points out that Vibram soles held “as well as Tricounis” on snow but excelled on rock. When ice demanded it, climbers simply added crampons.

The American Alpine Club’s history confirms that early crampons weighed about the same as modern ones but were less user-friendly, with straps prone to failure. Later step-in designs improved compatibility.

Environmental concerns also played a role. Nailed boots eroded rock more noticeably as climbing boomed after World War II. By Rebuffat’s era, “nailing has been abandoned to good purpose,” signaling the end of an age.

Vitale Bramani. Photo: Vibram Archives

Legacy

Today, Tricouni nails are largely a historical curiosity, revived occasionally by vintage enthusiasts or in niche applications like logging boots. Crampons, however, remain indispensable, with innovations like monopoints and heel spurs pushing boundaries in ice climbing. Modern debates, such as microspikes versus full crampons, echo the old “nailed-versus-detachable” discussions, focusing on convenience for moderate terrain.

Reflecting on this evolution, it’s clear that neither tool was inherently superior. Instead, they represented steps in a continuum of adaptation. As Eckenstein mused over a century ago, the limits of what’s possible continue to expand, built on the foundations laid by these early innovators.

Modern Grivel crampons. Photo: Grivel