“It was the most extraordinary human and alpinist experience I’ve ever had… because it spared my life, it let me taste its violence and its honey, the Queen of the Mountains… the Killer Mountain.” — Daniele Nardi, 2014.

It’s an old truism that death brings greater exposure to a mountaineer than life. Over the past two weeks, news anchors have chuntered, keyboards battered and printers rattled as media and public around the world have fixated on the search for Daniele Nardi and Tom Ballard on Nanga Parbat. With the discovery, through a long-distance photo, of the pair’s lifeless bodies, joined by a rope, haplessly strewn across a slope on the Mummery Spur, attention now turns to the reasons for their demise and to remembering how they lived.

Nardi had deep experience in the Himalaya, while Nanga Parbat was Ballard’s first 8,000’er. He was a precocious young talent who had made waves in the Alps. Their paths first crossed in 2017, when they attempted the North East face of Link Sar (7,041m) in the Karakorum, as part of an international expedition that included Ballard’s sister Kate. Beaten back by avalanches and poor snow conditions, Ballard recalled an Alfred Tennyson poem: “Cannon to right of them, Cannon to left of them, Cannon in front of them, Volleyed and thundered…” An omen, perhaps, of the fate that awaited on Nanga Parbat just two years later.

Forty-two-year-old Daniele Nardi was born in Sezze, Italy, a town not far from Rome. In 2002, in his mid-20s, he got his start on the big peaks by climbing Cho Oyu (8,188m). Over the next decade, he racked up five other 8000’ers: Everest (8,848m), Broad Peak (8,047m), K2 (8,611m), Nanga Parbat (8,125m) and Shishapangma (8,027m).

But it was to be Nanga Parbat in winter that captured his imagination. This year marked his fifth attempt to scale the peak in winter. Partnered with French climber Elisabeth Revol, Nardi reached a high point of 6,450m on the Mummery Spur in 2013, then made a solo attempt the following year but had to retreat from a height of 5,450m. Remarkably, in the same season, he also tried the Kinshofer route with Alex Txikon and Ali Sadpara, to no avail.

In 2016, Nardi missed out on the first winter ascent of the mountain. Despite opening the route to Camp 4, he disagreed with Simone Moro on the route ahead, and he turned around, leaving Alex Txikon, Ali Sadpara, Simone Moro and Tamara Lunger to claim the much-sought-after winter summit.

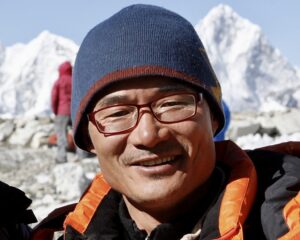

Daniele Nardi on Nanga Parbat in 2013. This was his second time on the mountain, but first in winter and first on the Mummery Spur. His partner on that climb, Elisabeth Revol, was dramatically rescued from the mountain in 2018. Photo: Daniele Nardi

Karim Shah Nizari, a Pakistani mountaineer from Gilgit, near Nanga Parbat, said: “Nardi was mentally very strong. He was highly motivated and had a different opinion from other climbers. He always said, ‘A climber is someone who climbs new routes’.”

But Shah Nizari also acknowledges that Nardi was “crazy” about these new routes and in particular, was obsessed with the difficulty of the Mummery Spur in winter.

An obsession with Nanga Parbat in winter has overcome a number of climbers in recent years. Tomasz Mackiewicz summited on his seventh winter attempt last year, while Elisabeth Revol, who reached the top with him, did so on her fourth try. However, Mackiewicz died on the descent and Revol was lucky to escape with her life, thanks to an international rescue in which Nardi played a large part as coordinator, something that has received little acknowledgement to date.

Nardi in happier times on Nanga Parbat, in 2013. Photo: Daniele Nardi

Some have speculated that not Nanga Parbat itself but the Mummery Spur was the undoing of Nardi and Ballard. Simone Moro didn’t hold back when he told The Times that climbing the Spur in winter was Russian roulette. “If we continue to say they were just unlucky, the risk is someone will die there next year,” he said. But some have wondered to what extent the disagreement between Moro and Nardi about their 2016 Nanga Parbat winter route prompted Moro’s outspoken criticism.

Shah Nizari believes that Nardi was able to tackle the Spur and would not have taken undue risks: “Three times he attempted the route and nothing happened, so it was not that dangerous for him. He was more familiar with Nanga Parbat and the Mummery Spur than any other climber in the world…”

Daniele Nardi receiving an award in Islamabad in December, 2018. Famed Pakistani mountaineer Nazir Sabir is on his left. Photo: Karim Shah Nizari

Despite his focus on technical winter climbing in the highest mountains, Nardi also set new routes in the Indian Garwhal Himalaya and Italian Alps. He received international recognition from the Piolet d’Or jury for two new lines — one in the Charakusa Valley in Pakistan, named Telegraph Road, and the second on Monte Rosa in Italy.

The talented and tenacious mountaineer hoped to build a mountaineering school in Pakistan to train rescue personnel. He leaves behind a wife and baby son. Shah Nizari remembers him saying, “Now I will be more careful because I am a father.”

The last supper in Islamabad. Nardi is second left, Ballard at right, poised to tuck into a gigantic plate of food. Photo: Karim Shah Nizari

Tom Ballard was over a decade younger than Nardi. He was born in 1988, in Belper, in England’s Peak District. In 1995, he and his family moved to the Scottish Highlands, so that his mother, Alison Hargreaves, could train on the local crags.

The tragic symmetry of the death of his famous mother on K2 in 1995 and his own demise on nearby Nanga Parbat has already become a media cliché. Much of the narrative focuses on the part her story played in her son becoming a climber. Even Ballard sometimes mentioned how he became the youngest to climb the Eiger North Wall, when his mother soloed the face in 1988 while six months pregnant. “Since I was 10, all I wanted to do was to climb. Even before I was born, I climbed the North Face of the Eiger. So I think it’s not much a surprise what I do now,” Ballard once said.

Ballard playing with toy cars at Everest Base Camp in 1994. In 1995 his mother, Alison Hargreaves, became the first woman to climb Everest solo without supplemental oxygen. Photo: Tom Ballard

But the focus should be on recognizing Ballard’s own climbing status. Growing up so close to Britain’s highest mountain, and with an obvious natural talent for climbing, Ballard soon began to put up new routes in Scotland. But it was a move to the Alps which really boosted his career. In 2009, at just 20, he established a new rock route called Seven Pillars of Wisdom, on the North Face of the Eiger. He particularly excelled in the Dolomites, where he climbed over 160 routes, including the first free ascent of the classic 1960 aid climb Via Olimpia in the winter of 2013.

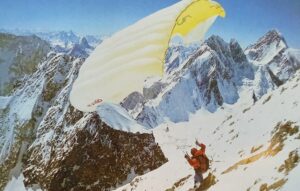

In 2016, he put up the hardest dry-tooling route in the world in a cave at the foot of Marmolada in the Dolomites, and he had also represented Great Britain on the Ice Climbing World Cup circuit. But his best-known and perhaps finest achievement was becoming the first person to solo all of the six great north faces of the Alps in a single winter, in 2014-2015. In so doing, he followed in the footsteps of his mother, who achieved the summer version of this feat in 1993. His climbs included Cima Grande (Comici), Piz Badile (Cassin), Matterhorn (Schmidt), Grandes Jorasses (Colton-MacIntyre), Petit Dru (Allain), and the Eiger (1938 Route). At the time, The Telegraph newspaper christened Ballard “The New King of the Alps“. Indeed, upon hearing of the style in which Ballard completed these routes, Reinhold Messner declared that modern alpinism was no longer moribund or in decay. A 2016 film documents this project; see the trailer below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=40LVB4sZB2c

Ballard soloing the North Face of the Matterhorn in 2015. Photo: Tom Ballard

Wim Stevenson, who works for Ballard’s sponsor, Montane, said: “Tom climbed with a tenacity that was both cerebral and instinctive. His routes served as more than just tests of ability, becoming love letters to the stone written in sweat and courage.”

British climber Alan Hinkes, who was with Alison Hargreaves on K2 at the time of her death, added: “Without doubt, he would have gone on to become one of Britain’s greatest, if not the greatest, mountaineers.”

Ballard cranking out the hardest dry-tool route in the world in 2016. Photo: Tom Ballard

Writing on social media, his girlfriend Stefania Pederiva said: “I will find you in nature, in the rivers in the trees in the mountains, you will always be my most beautiful rock”.

Self-portrait high on a route. Photo: Tom Ballard

And so like many others before them, this Italian’s and Brit’s story and achievements are now sadly and prematurely relegated to the annals of mountaineering: Mallory and Irvine, Boardman and Tasker, Kurz and Hinterstoisser, Ballard and Nardi…

Nardi and Ballard in Islamabad.