In the early 1800s, a Russian naval officer pored over his maps. A pesky question plagued him: Why was Russia no longer a leading exploratory power?

Adam Johann von Krusenstern set out to change things. Because of his persistence and determination, he expanded Russia’s reach in the Pacific and earned the respect of its naval rivals in the West.

Background

Of course, Russian exploration did not begin with Krusenstern. In 1787, Catherine the Great was keen on launching an expedition to the Pacific via the Cape of Good Hope to claim territory. She chose Captain Grigory Ivanovich Mulovsky to lead the expedition. However, the expedition was abruptly canceled when the Russo-Turkish War broke out.

Years later, Krusenstern decided to see the plan through.

A painting of Krusenstern.

After James Cook’s world-changing expeditions between 1768 and 1779, European powers vied to explore the uncharted Pacific Ocean. Explorers searched for resources, trade routes, and potential colony locations. But compared with other major maritime powers, such as Britain and France, Russia lagged behind.

Enter Krusenstern

Born in 1770 in what is now Estonia but was then part of the Russian Empire, Krusenstern came from a noble family with a military background. He received a good education, particularly in the sciences. This would serve him well.

Inspired by James Cook, Krusenstern entered the Russian Imperial Navy at 15 and quickly rose through the ranks.

Krusenstern’s early experiences serving on the Mediterranean and Baltic fleets exposed him to naval tactics, international trade, and politics. With the navy, he visited America, China, and India, setting the stage for his career as an explorer.

His role also brought important connections. Count Nikolay Petrovich Rumyantsev of the Russian-American Company later became his main patron. He even met Tsar Alexander I.

Krusenstern presented his plans for an expedition to the Pacific to Alexander I. Charismatic, well-spoken, and knowledgeable, Krusenstern convinced the Tsar, who approved the ambitious journey.

Krusenstern. Painting: Johann Friedrich Wietsch

Krusenstern believed that the discoveries of the Kamchatka Peninsula in 1696 and the Aleutian Islands (Alaska) in 1741 were two of the greatest achievements in Russian history. Those expeditions opened the door to the Pacific, and Krusenstern hoped to build on their work.

The expedition was organized hurriedly, as the Russian aristocracy was eager for him to begin.

“However flattering the enthusiasm with which the nation looked forward to this expedition, I was still not a little surprised to find that I was expected to set sail that same year,” Krusenstern wrote in a book about his voyages. Eventually, his departure was delayed by a year.

Krusenstern had a multidisciplinary mission in mind. Though establishing Russian relations with Japan and China was a top priority, he wanted to further scientific research in Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, and Oceania. He planned to take an anthropological approach, documenting the lives and cultures of native people along the way.

Preparations begin

He scurried to find the perfect ships for the mission, settling on two British merchant vessels. He named them Nadezhda (Hope) and Neva. Neva was originally called Thames, after the river. In keeping with the tradition, he renamed it Neva, after a river in northwestern Russia.

To pilot the Neva, Krusenstern chose Captain Yuri Lisyansky, a veteran of the Russo-Swedish War who had sailed around the world with the British.

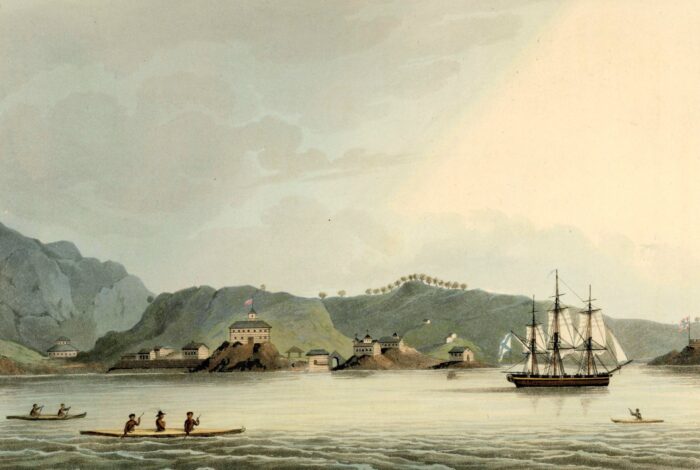

The Neva docks at St. Paul Harbor. Painting: Captain Lisiansky

Anchors aweigh

The expedition set off from St. Petersburg on Aug. 7, 1803. They sailed to Copenhagen and then Falmouth, England. From Europe, Krusenstern recruited scientists, navigators, and diplomats for the journey.

They stopped in Tenerife before crossing the Atlantic to Brazil. The two ships sailed around Cape Horn to enter the Pacific. This is where the expedition split up to tackle different objectives. Krusenstern and the Nadezhda sailed to the Marquesas Islands and Nukahiva Island, while the Neva sailed for Easter Island.

They rendezvoused in the Hawaiian (formerly Sandwich) Islands before separating again, with the Nadezhda heading to Kamchatka and Japan to establish diplomatic relations while the Neva went to southern Alaska.

While in Alaska, the Neva was pressed into military duty. It fought at the Battle of Sitka for the Russians against native Alaskans.

After, the ships met up again to sail to Macao and Canton, hoping to establish trade relations. However, this proved unfruitful despite offerings of bear skins and walrus bones. They returned to St Petersburg via the Cape of Good Hope, arriving in August 1806, almost exactly three years after they left.

Legacy

Though the expedition went down in Russian history as a great success, it failed in its objective: Neither Japan nor China were interested in pursuing a relationship with Russia.

Nevertheless, Krusenstern returned with a trove of information regarding resources, ethnic groups, marine life, oceanography, and botany. Krusenstern drew maps that aided later explorers, including his Atlas of the South Sea.

Krusenstern was also responsible for naming the Cook Islands. When James Cook visited in the 1770s, he called them the Hervey Islands. But in his atlas, Krusenstern called them the Cook Islands in the British explorer’s honor. The name stuck.

Krusenstern is commemorated in various ways. He lent his name to the Krusenstern Strait (which lies between the Russian mainland and Kamchatka), the Krusenstern Glacier in Antarctica, Mount Kruzenshstern in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago, and Cape Krusenstern in Alaska. The Moon even has a Krusenstern Crater.

Later, his son Paul Theodor and his nephew Otto von Krusenstern continued exploring, venturing further into Oceania and Western North America.