Say what you will about the British Empire in the early 1800s — and there’s lots to say about colonialism and the theft of important artifacts from other cultures — that rain-soaked collection of islands in the North Atlantic certainly produced some world-class adventurers. Thanks to well-funded institutions like the Royal Geographical Society, the UK sent out wave after wave of explorers willing to put their bodies and minds on the line for the sake of scientific exploration.

And sometimes a little cash.

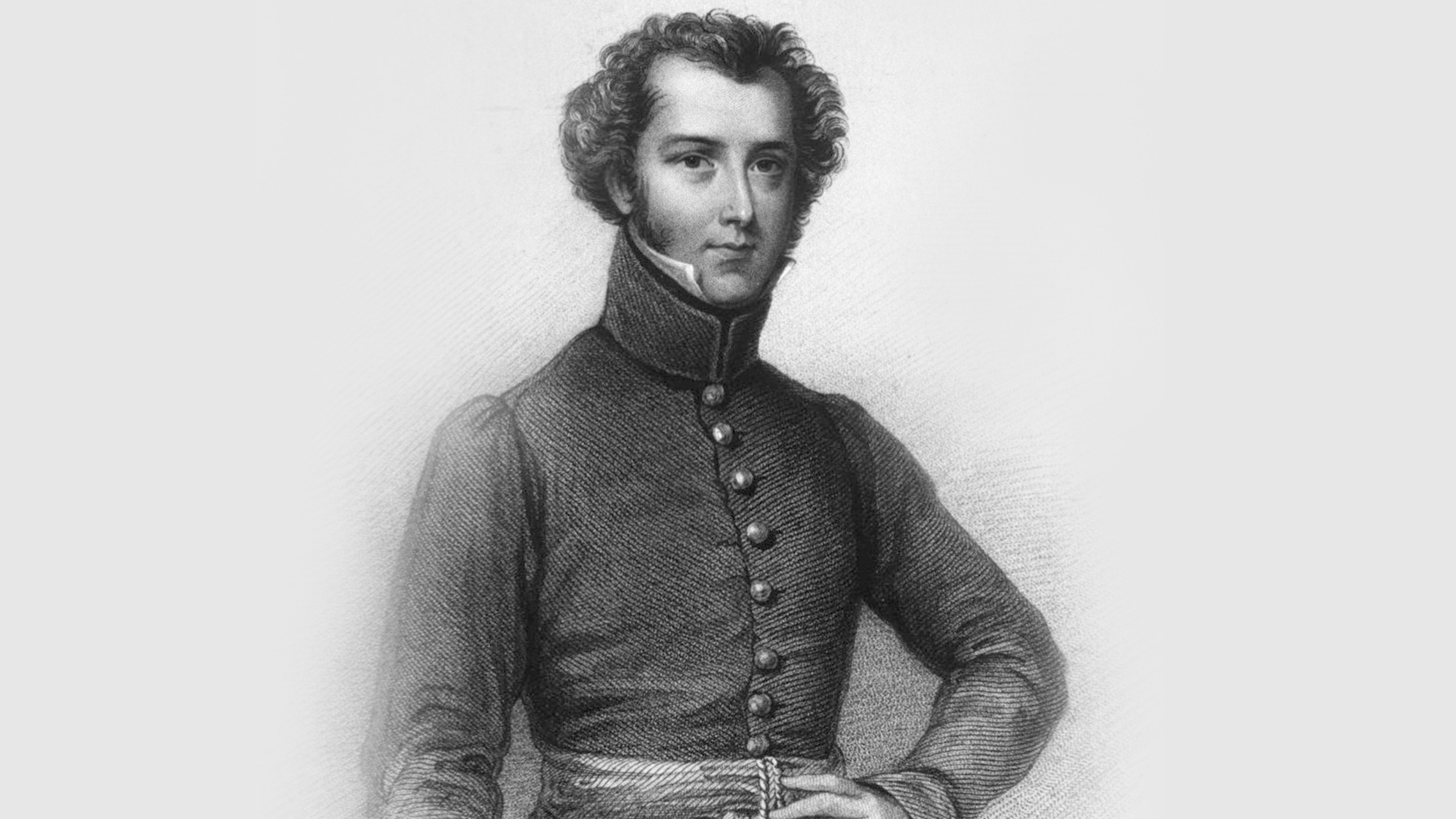

A monetary prize may or may not have played an important role in the sad finale of Alexander Gordon Laing’s story. Laing was a Scottish explorer and geographer tasked with finding the source of Africa’s Niger River. In pursuit of this goal, he suffered disease, maiming, and other hardships. He also became the first European to stumble into a city that had become virtually synonymous with “impossible-to-reach, mysterious places.”

Timbuktu: history becomes mystery

Timbuktu is an ancient city in West Africa, south of the formidable Saharan desert. And by ancient, I mean ancient: there’s archeological evidence for prehistoric settlements there. By the late Middle Ages, the city was a major trading hub and a jewel in the crown of Islamic culture.

But overland travel and geopolitical relationships being what they were five hundred years ago, Europeans didn’t go there. As centuries progressed, the word Timbuktu began to symbolize a place so far out of reach that it might be mythical.

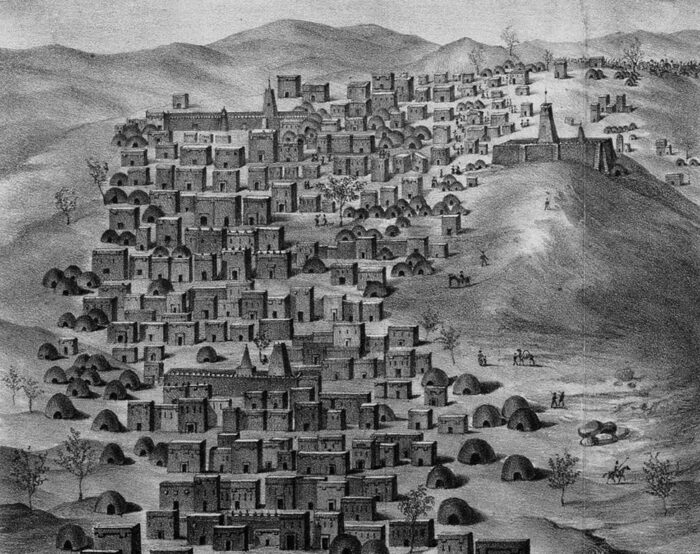

An artist’s conception of Timbuktu, circa 1830. Illustration: Wikimedia Commons

By the early 1800s, France was colonizing Mali, the country where Timbuktu sits. But even this didn’t make Timbuktu accessible to Europeans — the desert was simply too much of a geographical boundary for Europeans without the know-how and connections to travel its punishing expanse.

The Societe de Geographie (France’s version of the UK’s Royal Geographical Society) offered a 9,000 franc prize to any European who could reach the city and come back alive. As we’ll see, it’s this cash prize that may have led to our hero’s untimely demise at a far too young age.

A well-traveled young man

Like many young men of his time and station, Laing was well-educated and extensively traveled by his early adulthood. Laing was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1794. His father was a private tutor specializing in the classics. Laing would complete his higher education at the University of Edinburgh, one of the finest institutions of the day.

With that hefty education under his belt, 17-year-old Laing shipped out to Barbados to clerk for his uncle.

But two years with a desk, pen, and blotter was enough to teach Laing he wanted something different for his life. A military enrollment followed at age 19, and soon enough young Laing found himself first in India, then Africa. There, he journeyed extensively among the local people (primarily the Mandika), saw combat, and began his first explorations of West Africa’s rivers.

He was the first European to track the Rokel River (Sierra Leone’s largest waterway) to its source. Laing also launched the first of his expeditions up the Niger, a journey that was ultimately stymied by troublesome relations with the locals.

Shortly after, Laing was promoted to Major. He returned home to the UK in 1824 to prepare an account of his adventures, Travels in the Timannee, Kooranko, and Soolima Countries in Western Africa, published in 1825. He returned to Africa later that year.

Laing also found time for courtship amongst all these journeys. He married Emma Warrington, the daughter of a British consul, in Tripoli on July 14, 1825.

But a long and happy marriage was not to be Laing’s fate. Two days after his marriage, he set out into the desert on another adventure. It was destined to be his last.

South across the Sahara

Thanks to his demonstrated courage and extensive travels in the region, Henry, third Earl of Bathurst, secretary for the colonies, tapped Laing for another mission to the source of the Niger. And if Laing happened to reach Timbuktu along the way, all the better.

Things went well at first. In the company of a sheikh whose name is now lost to us, Laing first reached the oasis city of Ghadames (in modern-day Libya) and then the oasis city of In Salah (in modern-day Algeria).

But the toughest part of the desert yet remained. Ahead of Laing and the sheikh lay the flat, waterless, Tanezrouft, where summertime temperatures routinely reach 52°C. The Tanezrouft is so desolate and lifeless that, so far as archaeologists can tell, there has never been long-term human habitation. The Tanezrouft still presents travelers with difficulty today. Imagine traversing it in 1826.

A photo of a road sign in the Tanezrouft taken in 1990. This is not a place you’d like to be lost. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

But it wasn’t the heat that ultimately proved near-fatal for Laing in the Tanezrouft, but enemies both microbial and human.

Timbuktu, but no further

Like many European travelers in Africa, Laing was plagued with illness, particularly a devastating fever that severely weakened him.

That debilitated state certainly didn’t help when the caravan Laing was traveling with came under attack by bandits. The group fought the raiders, but Laing was robbed of his money and supplies and wounded in 24 places — including the loss of his right arm.

Despite encountering a setback that would have sent lesser men back to the relatively benign shores of the West African coast, Laing managed to limp into the trading town of Sidi Al Muktar. After a brief recovery, the dauntless explorer pressed on. On Aug. 18, Laing crested a dune and finally saw the fabled city of Timbuktu spread out before him.

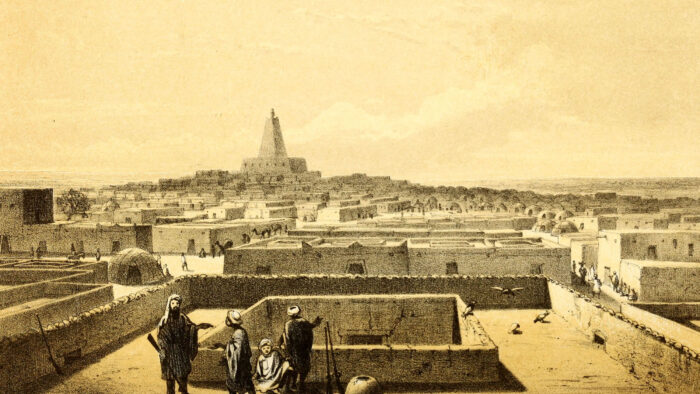

An illustration of Timbuktu dated 1858. It’s probably fairly close to what Laing saw when he reached the mysterious city. Illustration: Wikimedia Commons

The accomplishment cannot be overstated. Laing was the first European to reach Timbuktu in recorded history and the first to complete a north-to-south crossing of the Sahara.

Death in the desert

What happened next is where things get mysterious. After his death, Laing’s papers were never recovered, so all historians have to go on are the rather brief letters he sent home and some imperfect record-keeping from Timbuktu. It seems that Laing was an unwelcome guest in Timbuktu, and he swiftly made plans to leave and continue his search for the source of the Niger.

The one-armed explorer set out from the city on Sept. 24, 1826. Three days later, his Arab escorts murdered him and stole the few supplies he’d managed to cobble together. It was said at the time but never proven, that Laing’s nameless sheikh escort was involved in the plot. The young explorer was just 31.

Why did this happen? Laing’s influential father-in-law swiftly accused the French of masterminding the murder to allow a Frenchman to claim the 9,000-franc prize. He also claimed that the French had stolen Laing’s journal.

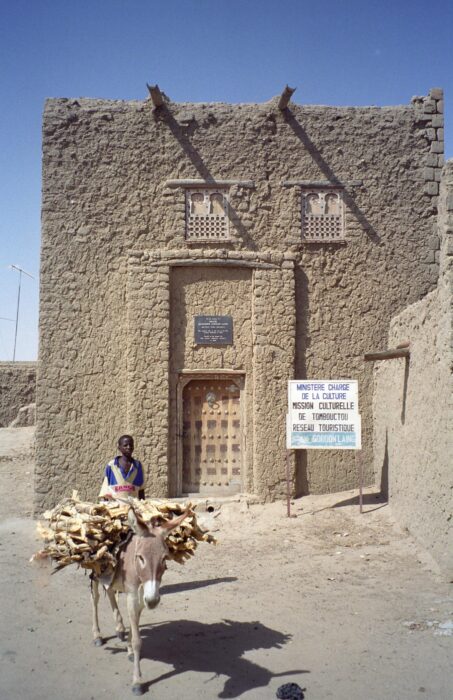

The house where Laing stayed while in Timbuktu is still standing. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

In fact, a Frenchman did end up succeeding where Laing failed. Two years after Laing’s death, a French explorer named Rene Caillie reached Timbuktu and survived the return journey. The prize was his.

But there’s no evidence that anything more nefarious than banal human violence and greed prompted Laing’s murder. In cases like this, Occam’s razor is a useful tool. Many were the European explorers of the day who found their infinitely less wealthy guides turning on them for profit. Laing’s journal, far less valuable than whatever money and supplies Laing was carrying, was likely tossed into the sand and lost to time.

An explorer gets his due

Today Laing is a barely remembered footnote in the history of African exploration. Towering figures like Livingston, Burton, Speke, and Carter are all more well-known for their contributions to European scientific knowledge of Africa. To add to this, it’s not as if Timbuktu was a “lost” city, it was an important trading hub, and certainly, the people who lived in and around it knew exactly where it was.

But we must remember the myriad difficulties faced by European adventurers as they explored the African interior. In many ways, setting off southward across the Sahara toward a city no European had ever seen was like getting into a rocket and blasting off into space without a flight plan, and just hoping to hit the moon.

The courage and physical resilience it took to do this — and to continue pressing on across the desert after severe wounds and disease struck him down — is astounding. Furthermore, nothing from Laing’s existing letters and papers indicates he was in it for the money. It seems as if the young Scot was exploring for the sake of knowledge, adventure, and the desire to “fill in the blank spaces” that so gripped certain Europeans of the day.

But Laing was not forgotten by the French, the very government his father-in-law accused of masterminding his death. When the Societe de Geographie awarded Rene Caillie its Gold Medal in 1830, it gave Laing one as well.

In 1903, the French also placed a plaque on the house where Laing stayed in Timbuktu. In 1992, it became a National Heritage site.