German naturalist and physician Engelbert Kaempfer started out as a small-town boy, the son of a local pastor. He never expected to become the world’s leading authority on Japan.

This was a time during the country’s period of isolation, when the few foreigners lived there. Kaempfer gave the world its first glimpse into life into secretive culture.

Background

In the 17th century, Japan closed its borders to foreigners in a unique foreign policy called the Sakoku. During the oppressive Tokugawa shogunate government, which ruled from 1603 to 1868, Japanese citizens were likewise forbidden from leaving. Trade and international relations withered during this time.

This extreme policy was a response to spread of Catholicism within Japan by Portuguese and Spanish missionaries. Such protectionism also encouraged economic growth and expansion of the arts.

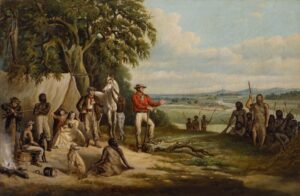

Nagasaki Bay, where the Dutch East India Company operated. Photo: Kawahara Keiga

An edict from 1636 stated that “Whoever discovers a Christian priest shall have a reward of 400 to 500 sheets of silver and for every Christian in proportion. All Namban (Portuguese and Spanish) who propagate the doctrine of the Catholics, or bear this scandalous name, shall be imprisoned.” Both priests and traders were expelled from the country out of fear of Christian uprisings.

Yet, some got away from the harsh treatment. The Japanese continued to build a trading relationship with the Chinese, a few kingdoms, and certain groups within Asia. The only European entity allowed to conduct business was the Dutch East India Company. To the Japanese, the Dutch posed less of a threat, as they tended to take a more secular approach.

Engelbert Kaempfer studied medicine and natural sciences at the Lutheran University of Königsberg in Prussia. He turned out to be a talented linguist and learned Dutch, Swedish, Portuguese, and Russian during those four years.

The Dutch East India Company

Despite his fulfilling education, he longed to explore the world beyond his borders. His insatiable wanderlust brought him to work for the Swedish ambassador. During this employment, he not only traveled frequently but found his niche in botany, establishing Sweden’s first botanical garden.

A trip to Persia launched his globetrotting career. As he and the ambassador traveled through Russia and Azerbaijan to Persia, Kaempfer documented and mapped a series of landmarks, including the Caspian Sea, the Volga River, and many volcanic formations. He also wrote insightful travelogues.

“Despite the haste in which these maps were made, they are of a remarkable exactitude,” wrote scholar Margarete Lazar. “Further proof of the outstanding scientific qualities of this renowned Baroque traveler.”

A year later, Kaempfer joined the Dutch East India Company as a doctor. But he was unhappy in Persia .He disliked the chaotic trader’s lifestyle and could not stand the hot weather. So he decided to sail for Japan, whose isolationist policies greatly intrigued him. Little information came out of the country apart from biased missionary accounts. Kaempfer wished to know more about Japan and especially local flora and Japanese cultural traditions.

Kaempfer’s sketch of Hokoji Daibutsu. Photo: British Library

At first, the Japanese did not take kindly to a foreigner prying into their lives. But his profession as a physician and scientist helped gain their trust. Slowly, they opened up to him. He taught them various subjects, including mathematics, and applied Western medicine to their ills. Kaempfer even took on a local apprentice who gave him valuable information about Japanese customs, medicinal practices, and plants.

He also established amicable relationships by speaking the international language of alcohol. He wrote that by “liberally assisting them…with a cordial and plentiful supply of European liquors…there was none that ever refused to give me all the information he could.”

Thanks to his new connections, he conducted long studies into plants, religious practices, and Oriental medicine.

A smuggler of information

In 1692, after two years in Japan, Kaempfer left the country and started writing about his travels in Persia, Japanese botany, and medicine. He called this compendium the Amoenitatum exoticarum. It was published in 1712, toward the end of his life.

In it, he detailed Persian culture, botany, geography, the 232 species of plants he found in Japan, and Oriental medicinal practices like acupuncture. Because of the strict Japanese laws, he had to smuggle much of his information out of the country illegally. He hid manuscripts, botanical samples, maps, and notes about the country’s history, flora, fauna, natural resources, arts, and religions.

He also gave the first scientific descriptions of hyenas and Ginkgo trees. As a result of his accomplishment, the University of Leiden awarded him with a doctorate.

When he passed away in 1716, he left behind a series of unpublished manuscripts which turned into his famous History of Japan. His nephew sold them to Sir Hans Sloane, a fellow naturalist and esteemed physician. Sloane’s collections helped start the British and Natural History Museum and British Library.

Sir Hans Sloane. Photo: Alchetron

Kaempfer’s History of Japan “was the most comprehensive European account of Japan for over a century and the first such work in English,” according to the Royal Collections Trust. Its 427 pages covered Japan’s history, political structure, and other aspects of Japanese society. Some of his observations even challenged the European perspective on the country. Most people saw Japan as alien, mysterious, and sometimes barbaric.

Legacy

Kaempfer’s curiosity and drive to explore gave anthropologists and historians a wealth on information on East Asia in a time of scarcity. If not for him, the world would have lacked even a basic understanding of the East, and of alternative forms of medicine, botany, and zoology.