As a dedicated technophobe, I’ve always felt a certain kinship with the English explorer H.W. Tilman (1898-1977), who would have thrown a GPS into the trash, assuming he ever had one. On his mountaineering expeditions, he engaged in alpine-style climbing and refused to bring any oxygen equipment with him, while in his seafaring trips, his boats carried no technical devices other than a compass, a sextant, and a short-wave radio. Nor did those boats have engines, since he preferred to be under sail. “Radar is a superstition,” he once wrote.

In 1986, I was in the village of Angmagssalik (now Tasiilaq), East Greenland, and I happened to ask a local Danish shipbuilder if he’d ever met Tilman, who’d visited these parts several times in his pilot cutter Mischief.

“Funny you should ask me that,” the fellow said. “I repaired the Mischief in 1973 when it was struck by ice floes. While I was doing my repairs, Tilman climbed that mountain over there every day” — here he pointed to a steep icy mountain — “to examine the ice conditions in the fiord. Or that’s what he told me. I actually think he climbed the mountain just for the hell of it. Because he was that sort of guy. By the way, he must have been 75 years old at the time.”

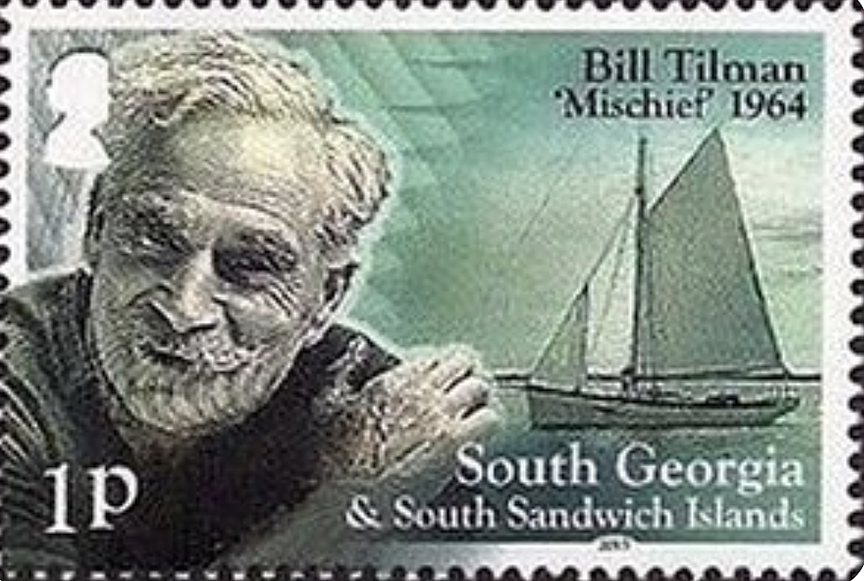

Tilman on the ‘Mischief.’

Just walk out the door

Tilman was indeed “that sort of guy.” A would-be explorer once asked him how he could get on an expedition, and “Bill” (as his acquaintances called him) replied, “Put on a good pair of boots and walk out the door.” He himself lit out for the territory whenever possible. For him, that territory included the battlefields of war (he served valiantly in World War I), the wilds of Africa (he bicycled east to west cross the continent — a first), the Himalaya (he made the first ascent of Nanda Devi in 1936), Patagonia (he sailed through the notoriously difficult Strait of Magellan), or some remote part of the Arctic.

So how did he travel? By foot, by boat, or by bicycle. “Only a man in the devil of a hurry would fly to his mountain, foregoing the lingering pleasure and mounting excitement of a slow, arduous approach,” he once wrote. He seemed never to be in the devil of a hurry himself, which makes him quite different from a number of better-known explorers.

Tabasco sauce essential

Like many an English explorer, Tilman was something of an eccentric. Or maybe he was just a man who marched to the beat of his own drummer. You can experience his idiosyncratic march by reading any of his 15 travel books, particularly the Mischief ones.

In doing so, you’ll learn that he thought Tabasco sauce was an essential item to be brought on an expedition, since anything, even lifeboat biscuits (i.e., hardtack), could be made edible with a few drops of it. You’ll also learn that he advertised his Mischief expeditions with these words: “Hand wanted for long voyage in small boat. No pay, no prospects, not much pleasure.” Believe it or not, he got plenty of enthusiastic replies.

Since I’m an arctic hand myself, I have a particular interest in Tilman’s arctic expeditions, all of which took place in his later years and featured the Mischief as well as another pilot cutter called the Sea Breeze. Among the reasons he liked the Arctic was that he didn’t have to submit to any authority other than himself.

“No bother, no police, no customs, no immigration or health officials to harry us,” he wrote about it.

He could have added something like “only a wondrous natural world” to end this description. At 3,000 feet on a mountain in Greenland, he found a yellow poppy and was utterly enchanted!

A hard trek at age 65

Bylot Island is rugged island off the northwest coast of Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic. Taking a boat from the Inuit village of Pond Inlet, I once tried to hike across it, but I didn’t get very far before my energy gave out. Not so Tilman! At age 65, he was considerably older than I was, but he made a first crossing of the island in 15 days. That crossing included negotiating his way over an ice col that was 5,000 feet above sea level. “The hardest 50 miles I have ever done,” he said with a grin.

Photo: Wikipedia

Even more remote than Bylot is Jan Mayen, a Norway-owned island to the east of Greenland. Rising up from it is Beerenberg, a 7,470 foot mountain that’s the northernmost active volcano in the world. I climbed it in three days and ended up being blanketed by volcano ash. One of my companions who didn’t make the climb claimed not to recognize me when I returned to our base camp.

Tilman himself was eager to climb Beerenberg, but before he could do so, the Mischief got stuck on an offshore rock. A goodly percentage of the boat’s supplies were lost, but the item he most lamented the loss of was his pipe. The Norwegians who manned the island’s weather station tried to save the Mischief, but to no avail. Tilman felt like he’d witnessed the death of a dear friend. Even so, he found another friend in the Sea Breeze, and the following year he stopped at Jan Mayen en route to Scoresbysund in East Greenland. “Mr. Tilman, I presume?” one of the Norwegians said to him.

Hunger for adventure grew stronger

As he aged, his desire for adventure seemed to grow stronger. He wanted to spend his 80th birthday in the Arctic, but since that birthday was in February, Antarctica seemed like a more appropriate destination. Thus he sailed south in a gaff-rigged cutter called En Avant with a young explorer named Simon Richardson. In Rio de Janeiro, he sent letters to several of his friends in England. Then — silence. The En Avant vanished without a trace somewhere in the South Atlantic. Tilman was doubtless pleased to have breathed his last in this fashion rather than in a hospital or an old folks home.

My thanks to librarian Mary Sears for providing me with some obscure facts about Tilman’s life.