Not long after Marco Polo traveled further than anyone in the 13th century, an eccentric character named Ibn Battuta surpassed him and all explorers of the time. Perhaps the greatest explorer of the Islamic world, Ibn Battuta traveled over 120,000km to 44 countries over a 30-year period in the 14th century. No one else accumulated similar distances until centuries later.

Early wanderlust

He was born into a middle-class Sunni Muslim family of judges in Tangiers, Morocco. He was well-educated and planned to be a judge at one point but inborn wanderlust disrupted any early conventional notions.

“I set out alone…swayed by an overmastering impulse within me and a desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit these illustrious sanctuaries,” he recalled years later. “I braced my resolution to quit my dear ones, female and male, and forsook my home as birds forsake their nests.”

And so at just 21 years old, he left home to go on a hajj, a Muslim’s obligatory pilgrimage to Mecca. However, rather than returning home, he chose to embark on an extended 30-year journey all over the Middle East, Asia, the Iberian Peninsula, some parts of Europe, and North Africa. He mainly stuck to the Islamic world and seldom branched off to visit Christian or pagan lands.

A tireless traveler

His pit stops read like an exhaustive inventory of that part of the world. He jumped from caravan to caravan to Mecca, Medina, Iraq, Iran, Damascus, Yemen, Cairo, the Levant, Tunis, the Arabian Peninsula, Somalia, Swahili Coast, Mali, Azerbaijan, the Aral Sea, Afghanistan, India, Sri Lanka, the Hindu Kush, the Maldives and as far as China. He also visited Constantinople, Anatolia, Bulgaria and Andalusia.

The Christian world was quite a shock to him. He spoke of how Christians ate pork and drank alcohol. He did not bother to go inside churches or cathedrals. His visit took place a century and a half before the Ottoman Empire conquered that part of Christendom.

His main mode of travel was by caravan. It was safer that way. Bandits were common, and a solo traveler was a prime target. Travel in that era featured other dangers, and Ibn Battuta almost died several times — in a shipwreck, robbed and attacked by highwaymen, sentenced to beheading, and sickness on the road. He also managed to survive the Black Death. Constant strokes of good luck allowed him to survive all these obstacles.

Ibn Battuta in Egypt. Photo: Leon Benett (1878)

Charisma

He must have been a charismatic man, as he notably charmed the nobility he met en route, including sultans, viziers, governors, ambassadors and the like. Battuta used many of these political relationships to his advantage, securing gifts, favors and social mobility. He met over 60 rulers in his lifetime. He even married into a royal family in the Maldives and aspired to become the country’s sultan. However, these relationships did not always last. Over time, he got cocky, and local nobles distrusted him. Sometimes, things soured so much that he had to flee for his life.

He was also a noted Casanova, at least in the style of the time. Wherever he traveled, he married a woman briefly before divorcing her and moving on the next place, only to repeat the cycle again. During his three decades of vagabonding, he took over 10 wives and fathered many children. Additionally, he took concubines and slave girls and even had a harem at one point. Battuta does not hide these details and sees them as completely normal.

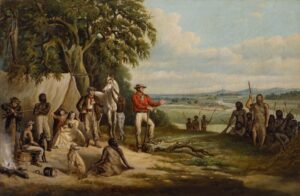

Ibn Battuta map. Photo: Bayt Al Fann

“Ibn Battuta makes no secret of his private life,” comments Mahid Husain of the University of Baroda. “[He] explains how freely he moved in society and how closely he mixed with different classes of Muslims and how easy it was for him to marry into respectable families.”

Husain also states that “he disposes of knotty cases of divorce with skill and ease and relates the story of his successive marriages, ‘matrimonial contracts’ and separations.”

This shows Battuta to be quite strategic — almost Machiavellian — in his personal life. Most of his interpersonal relationships were political and beneficial to him. They were rarely out of love. Maybe this had to do with the fact that a couple of holy men had told him of his destiny to see the world. He evidently interpreted this to mean that the world was his for the taking, without much consequence.

The Rhila

Although there is no evidence that Battuta kept notes of his travels, he dictated his life story and observations to a scholar named Ibn Juzayy in 1353, by order of the Sultan of Morocco.

That account, titled A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling, shortened as the “Rihla,” thoroughly portrays the religious, social, intellectual, political, military, and psychological aspects of the societies in which he traveled.

It was never meant to be an accurate geographical work or even a historical one. Rather, it is anthropological in nature, offering glimpses into a variety of cultures spread throughout the Islamic world. It is more like a diary or travelogue, taking the reader on the journey with him. He drew distinctions between countries and cultures. For example, he compared Muslim women with Hindu women in terms of their beauty, temperament, and fashion. He commented on slavery practices, military, intelligence services, and art.

Not all of his travels might have been accurate. There are some discrepancies in his accounts, particularly with dates. This has caused scholars to doubt his travels to certain places like Bulgaria, Yemen, and China. It is possible that his compiler, Juzayy, embellished the work with additionally details from other travelers. Nevertheless, this has not deterred his readers from experiencing the same wonderment he did.

Conclusion

After he retired from traveling, Ibn Battuta disappeared. We do not know if he ever hit the road again or retired to a somewhat normal life. One thing is for sure. His travel came with a cost. This restless man missed out on many life events. For example, he didn’t learn about the death of his beloved father until 15 years later.