Here’s a recipe. Take one part larger-than-life figure, add two parts adventurous exploits, a dash of some of the most rugged country in the world, and salt liberally with the passage of time. That’s how you get legend.

But what happens if you sprinkle fabrication into the mix?

The dish changes completely.

The history of the American West is overflowing with figures who had no shame about exaggerating — or in some cases, outright lying about — their achievements. When that happens, it becomes difficult to untangle the threads of history from the Gordian Knot of tall tales.

Perhaps no one in American exploration fit that bill better than Jim Bridger. An explorer, a trapper, a scout, and the first white man to lay eyes on large swathes of the American West, Bridger was iconic in his day. And he lived long enough to mythologize his own deeds.

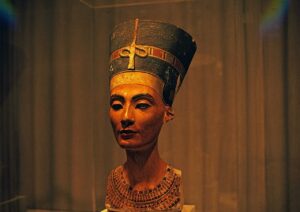

A statue of Jim Bridger in his prime. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

And though his name is now less recognizable than other early North American explorers like Lewis and Clark or Daniel Boone, his contributions to settling the West were invaluable to the many pioneers who tracked across the young country in search of opportunity.

The story that follows will feature the word “probably” quite heavily. “Possibly” and “according to Bridger” will pop up often as well. It’s the price to pay when looking back through a telescope well-smudged by Bridger’s tendency to play fast and loose with the facts. It’s all part of the man’s mystique, and when primary sources and trustworthy stories fail us, we must make do with legend.

Luckily, legends are fun.

A track ever westward

James Felix Bridger was born the son of an innkeeper in Richmond, Virginia, but didn’t stay in the East for long. His family relocated to St. Louis when Bridger was eight. Tragedy struck at the age of 13 when young Bridger was orphaned, and he found himself alone, illiterate, in a hardscrabble world.

He spent the rest of his teenage years apprenticed to a blacksmith. Coming of age on the edge of the frontier must have nourished the wanderlust in his soul. At 18 — in other words, practically the minute his apprenticeship ended — Bridger came across an advertisement in a local newspaper. The brief words therein changed Bridger’s life forever — and by extension, the lives of thousands of others.

“To Enterprising Young Men. The subscriber wishes to engage ONE HUNDRED MEN, to ascend the river Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years. Wm. H. Ashley.”

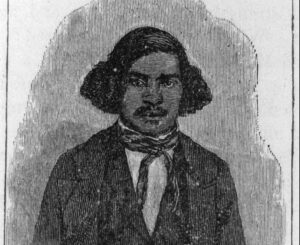

The advertisement that sparked Bridger’s life of adventure. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Eighteen-year-old Bridger was one of the enterprising young men who responded. Soon, he found himself trapping on the Missouri in the employ of Ashley’s Rocky Mountain Fur Company. The year was 1822. In one short year, the dual threads of history and legend began twining for the first time.

The Hugh Glass Incident

In 1823, after enduring Native American attacks and poor pelt takes on the Missouri, a group of Rocky Mountain Fur Company trappers led by Andrew Henry struck out for a fort at the mouth of the Yellowstone River. Bridger was — here’s the word — probably with the group.

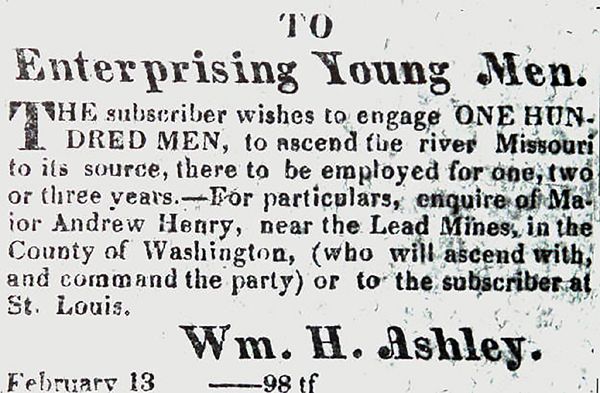

A trapper and scout named Hugh Glass was also along. Glass was the party’s designated hunter. While scouting for game along a brushy river bottom, he encountered a mother grizzly and her two cubs.

The bear turned on Glass with instant rage, mauling him severely. Hearing his screams, the rest of the party approached and killed the bear. The men didn’t believe Glass would live through the night, but come morning, the tough scout was still drawing breath. Henry ordered his party to build a litter, and for two days, they attempted to carry Glass to safety.

However, the pace of travel was too slow, and Henry was concerned about further altercations with tribes in the area. Assuming that Glass would die eventually, he paid two men $80 to stay behind.

Bridger was probably one of these men.

Hugh Glass runs into trouble. Illustration: Wikimedia Commons

Abandoned the gravely injured man

Bridger and the other man, John Fitzgerald, stood a death watch for five days, but still Glass hung on. Cognizant of dropping further behind the rest of the party with each passing hour, and with the ever-present danger of Native American attack looming like a prairie thundercloud, Fitzgerald and Bridger abandoned the still-living Glass near a spring. They took the injured man’s rifle, knife, tomahawk, and fire kit, and lit out for the mouth of the Yellowstone.

Glass survived, and the ordeal that followed became the subject of its own legend. It’s an incredible epic but outside the scope of this story. Instead, it’s worth pausing here a moment to consider the sources for this tale, then turn our attention to the character of Jim Bridger.

First, though tradition has now calcified Bridger as being the young man left behind with Glass and Fitzgerald, original accounts of the story didn’t put names to the characters other than Glass. It’s not until 1839 — 16 years later — that a writer named Edmund Flagg penned a telling of the story that included names. In this account, the youth in the story is identified as Bridges.

It was not until the 1890s that oral accounts collected by biographers and historians identified Jim Bridger (by then a household name) as the young man involved in the Hugh Glass incident.

Was Bridger even there?

So was Jim Bridger one of the men who abandoned Glass near that spring, taking his kit as they hurried to safety? We’ll never know for sure. But we know Bridger was working for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company when Glass was injured. We also know that among the close-knit mountain man society of the time, the abandonment of Glass — and especially the confiscation of his gear — was as close to sacrilege as that rough-and-tumble society could imagine. It seems unlikely that Bridger would have taken credit for such an act if he wasn’t really there, especially as his fame rose among later pioneers.

If Bridger was there, it’s important to remember he was only 19, in serious lack of a father figure and subservient to the much more experienced Fitzgerald. Both oral tradition and Glass’ own accounts absolve the young man of guilt over the matter, instead reserving all the blame for Fitzgerald. The story goes that Glass caught up with Bridger at Fort Henry on New Year’s Eve, 1823, and — after hearing Bridger’s version of events — spared the young man’s life.

And that’s a lucky thing for history, because Bridger had a lot left to accomplish.

Explorations further west

A year and some change later, young Bridger, now equipped with more life experience than most people gather in a decade, found himself in the high, arid, shockingly beautiful landscape that would one day become Utah.

Still with Ashley’s Rocky Mountain Fur Company, Bridger was selected to settle a question about the course of the Bear River, a waterway that rises in northeastern Utah and flows northwest through Wyoming and Idaho before confusingly turning south again. Bridger’s aim was to discover where it terminated, and what he found was a lake so large and salty that he believed it was part of the Pacific Ocean.

The Great Salt Lake. Photo: Shutterstock

Thus, Bridger became the first white man to lay eyes on the Great Salt Lake.

Bridger eventually parted ways with the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and worked as an independent trapper. But by 1830, he and three partners raised enough capital to buy the company outright. While the venture was successful, Bridger’s itchy feet prevented him from enjoying the life of a businessman. He sold his stake in the company in 1834 and married the daughter of a local Native American chief.

Yellowstone trails

Bridger and his wife trapped together for a few years before Bridger got a new idea — establish a trading post along the now thriving Oregon Trail. Fort Bridger was a success, and Bridger, now an experienced frontiersman with 20 years of adventuring on his resumé, acted as an advisor and guide to the many pioneers who traveled through.

A historical recreation of Fort Bridger along the Oregon Trail. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The post’s location also gave Bridger the opportunity to explore one of the most famous spots in America.

Two hundred and fifty miles north of Fort Bridger lay the area that would one day become Yellowstone National Park. Bridger may have been the first white man to see it as well. It’s at this point in the story that Bridger becomes known as a teller of tall tales.

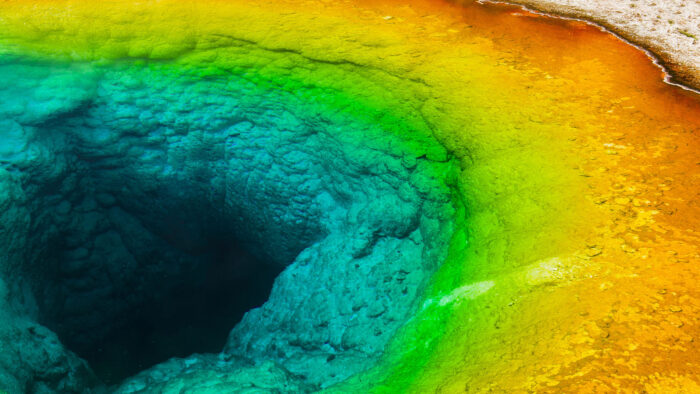

Not content with legitimate descriptions of multi-hued hot springs, exploding geysers, and sparkling, fish-laden streams, Bridger also spun stories of a petrified forest that contained “petrified birds that sang petrified songs.”

He spoke of a “mountain of pure glass.” In Bridger’s telling, he took aim at an elk he believed was in range, but his shot had no effect. Walking closer, Bridger realized the elk was far in the distance but being magnified as an optical illusion through the so-called glass mountain.

If Jim Bridger was telling you about this multi-colored hot spring in Yellowstone, would you believe him? Photo: Shutterstock

Despite the obvious falsehood of these tales, Bridger’s exploration of Yellowstone — and the way he sold its beauty and mystery to the thousands of Americans who passed through Fort Bridger — are credited by many historians as one of the factors that led to its preservation as a national park by the 42nd U.S. Congress and President Ulysses S. Grant in 1872.

Passes, trails, and fatal mistakes

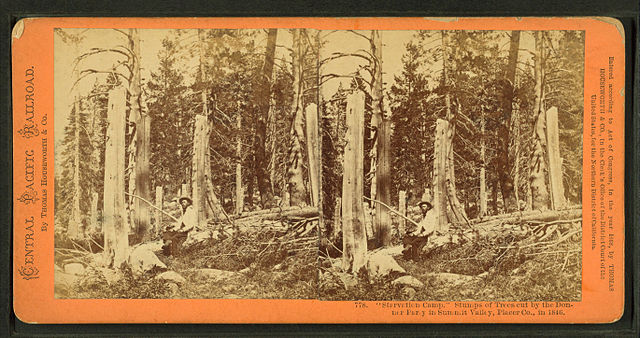

Bridger commanded his trading post until 1853. During that time, he blazed trails, offered advice, and otherwise assisted the travelers on their way to Oregon. But a mistake in 1846 forever connected him to the fate of one of the West’s most famous disasters — the ordeal of the Donner Party.

The group was already running behind schedule and needed to cross the Sierra Nevada before the first snows fell. But first, they had to make it across Utah.

The pioneers had in mind an alternate route that dipped south below the Great Salt Lake rather than running above it, as the established Oregon Trail did. The route was first proposed by an ex-Confederate soldier named Lansford Hastings, who went to great trouble to publicize the route.

A photo of tree stumps cut for firewood by the Donner Party in the winter of 1846-47. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It’s unknown if Bridger and his business partner had scouted the route and misjudged its difficulty and length or had just been paid by Hastings to recommend it. Regardless, it’s one of the few black marks on Bridger’s character — aside from the Hugh Glass incident.

The Donner Party

The route ended up being twice the length that Hastings had advertised and much more difficult for the Donner Party’s wagons and pack animals than they were expecting. The resulting delay ended in the death of most of the party after it became snowed in at a small lake just shy of the Sierra crest some months later.

Perhaps seeking redemption, perhaps just a victim of his eternally restless spirit, Bridger sold his trading post in 1858 and became a scout in the so-called Indian Wars that characterized much of the mid-to-late 1800s in the American West. Bridger would spend the next decade and a half assisting various armies and expeditions in the conflicts that followed.

But before he did, he managed to shorten the Oregon Trail by 100 kilometers after discovering a pass over the Continental Divide in Wyoming. Travelers on the Oregon Trail swiftly adopted the pass. In later years, it became the route of choice for the Pony Express, the Overland Stage, the Union Pacific Railroad Overland Route, and, finally, Interstate 80.

It’s still called Bridger Pass to this day.

Final years and legacy

Bridger’s middle age and declining years were characterized by much personal loss. Though he remained illiterate all his days, he was a skilled linguist, and each of the three women he married in his adventurous life belonged to native tribes. His first wife died of illness in 1846, and his second wife died in labor in 1849. In 1850, he married for a third time.

Between all his marriages, he produced five children, but only one, his daughter Virginia, lived past early adulthood. It was Virginia who eventually cared for Bridger in the late 1860s and early 1870s, when the aches and ailments of life at the fringes of society finally began to take their toll.

His eyesight began failing during this time, and by 1875, he was completely blind.

The old scout finally passed away in 1881 on a farm in Kansas City, Missouri. One of life’s great mysteries is what would draw such a widely traveled and passionate wanderer back almost exactly to where he began.

What does home mean to such a man — an orphan who lit out for the Missouri River the first chance he got and never looked back until the very end?

The stuff of myth

In any case, Bridger’s life and achievements were already the stuff of myth by the time he passed, helped along by newspapers, periodicals, and the ever-ravenous American appetite for tales of the high prairie, soaring peaks, and expansive desert.

Today, he’s remembered mostly thanks to his possible involvement in the Hugh Glass affair, which became a feature film starring Leonardo DiCaprio. But without his explorations, much of American history would likely be different. Would Yellowstone still be a national park? How many Oregon pioneers would have died without Bridger Pass? What would the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, so instrumental in the shaping of Utah, have been without the Great Salt Lake?

Like separating the myth from the legend from the fact, it’s hard, if not impossible, to say.