Skilled explorer or overreaching dilettante? Crusading abolitionist or violent murderer? General with the soul of a country on his mind? Or self-centered opportunist only interested in tapping the zeitgeist to make a buck?

All of these charges, both positive and negative, have been laid at the feet of John C. Fremont in the last 150 years. Over the course of a turbulent and adventurous life, Fremont managed to embody all of the above and more. In the process, he became one of America’s biggest celebrities before that word had even been coined.

Historians’ opinions on John C. Fremont have ebbed and flowed over the years, but what is certain is that the man who’d be known to the American public as “Pathfinder” was well-traveled, deeply complex, and seriously flawed.

Fremont’s beginnings

Born in 1813, Fremont was an unpredictable character who greatly disliked authority, even at an early age. That streak continued through his adult life and put him in trouble with his superiors more than once.

He was highly intelligent, though. “In the space of a year,” said U.S. Senator George S. Boutwell of Massachusetts, “Fremont read four books of Caesar…six books of Virgil…Horace…two books of Livy…and four books of Homer’s Iliad.”

Finding himself in the military but possessed of an allergy to bureaucracy and academia, Fremont declined a naval position as a math teacher. Instead, he took a more exciting post as a surveyor and railroad engineer. Through this avenue, he joined the Topographical Corps and began to lead expeditions for President Martin Van Buren.

John Fremont, 1856. Photo: Library of Congress

Manifest Destiny

Fremont led a total of five expeditions through the western frontier from 1842 to 1853. They first explored the Oregon Trail and the South Pass, which cut through the Continental Divide. Oregon was at the forefront of politicians’ minds, often called a “pioneer’s paradise” thanks to its fertile land, navigable rivers, and opportunities for trade. This early expedition counted among its ranks the legendary Kit Carson, himself an iconic figure in the opening of the American West to settlers of European descent.

Along the way, Fremont climbed a 4,189m mountain in Wyoming’s Wind River Range. In the style of the day, he named it after himself. Fremont’s Peak became the official marker of the United States’ acquisition of the Rockies and, by extension, the West.

He noted down all that he saw, drawing maps as he went, which assisted explorers after him. Fremont returned a conquering hero after five months on the trail. He received the nickname Pathfinder, though it must be said that many of his plaudits were generated by his own knack for publicity — and a fortuitous marriage.

Marry up

Fremont’s wife, Jessie, was the daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, who chaired the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. Through this fortunate connection, Fremont received both wider exposure to America’s upper crust and the funding to pursue his expeditions. And when he returned from the first of them, it was Jessie who helped him write an account of the trip.

“The horseback life, the sleep in the open air,” she said later, “had unfitted Mr. Fremont for the indoor work of writing.”

Jessie Benton Fremont later in life. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Taking up the pen herself, Jessie filtered her husband’s notes and dictations, producing a work called Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains, 1843. The account’s publication in newspapers across the country was the start of Fremont’s fame and helped secure funding for future expeditions. And why not? Under Jessie’s dutiful authorial skills, Fremont’s wanderings in service of his young country became something more romantic.

“Railroads followed the lines of his journeyings…and cities have risen on the ashes of his lonely campfires,” she declared in one report. These lush tales of the West encouraged people to pack up their lives and risk the unknown.

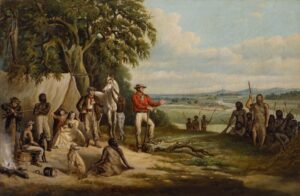

America personified as an angelic being venturing westward, a romantic interpretation of Manifest Destiny seized upon by Fremont’s wife in her writings. Painting: John Gast, 1872

Second and third expeditions

In his second expedition, Fremont (again with Kit Carson at his side) explored and mapped the Great Salt Lake, Mount St. Helens, the Sierra Nevada, the Great Basin, and Lake Tahoe. He confirmed that a rumored Buenaventura River did not exist, despite the assurances of previous explorers such as Atanasio Dominguez and Alexander von Humboldt. And that’s just his second expedition!

Unfortunately, violent encounters with Native Americans stained Fremont’s standing with future historians. His third expedition occurred on the eve of the Mexican-American war, and the explorer was under orders to bend his will toward military matters should the need arise. Fremont embraced the new direction.

Traveling back and forth from California to Oregon, Fremont and a band of men comprising 60 white explorers and a handful of Native Americans participated in a series of three encounters known to history as the Sacramento River Massacre, Klamath Lake Massacre, and South Butte Massacre.

Native American massacres

Contemporary accounts by members of the expedition and other witnesses put the numbers of dead Native Americans at anywhere between 100 and 900 in the Sacramento River Massacre alone. Men, women, and children were shot, trampled, and tomahawked to death indiscriminately. Many more drowned in the Sacramento River while trying to escape. In his memoirs, Kit Carson later described the event as “perfect butchery.”

In another set of memoirs, expedition member Thomas E. Breckenridge wrote:

“I think that I hate an Indian as badly as anybody and have a good reason to hate them, but I don’t think that I could have assisted in that slaughter. It takes two to fight or quarrel but in that case, there was but one side fighting and the other side trying to escape.”

Three days later, Fremont’s party killed 14 members of the Klamath people in the Klamath Lake Massacre, then attacked a group of Patwin people after hearing rumors they were planning on attacking Whites in the area. In his own memoirs, the explorer admitted to attacking the native band before they had done any violence of their own. History knows this event as the South Butte Massacre.

Neither Fremont nor any member of his party was ever held to legal account for these happenings.

California politics

As the Mexican-American war broke out, Fremont found himself engaged in a kind of guerilla warfare on behalf of the United States in the California region. He was so successful that in 1847, he was appointed the military governor of California.

However, shortly thereafter, a contradictory set of orders placed U.S. Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny in the same position, and the two men clashed over who was really in charge. The resulting tangle of egos, orders, communications, and troop movements — confusing even at the time and even more so now when viewed through the fog of history — resulted in Fremont’s court-martial.

Thanks to his powerful father-in-law, successful campaigns in the Mexican-American War, and popularity with the American public (thanks, Jessie), President James K. Polk commuted Fremont’s sentence and re-instated him to the Army. But the always prickly Fremont resigned and settled in California.

But not for long. More adventures (and controversy) beckoned.

Railroads and Republicans

Fremont’s fourth and fifth expeditions were private affairs on behalf of railroad companies. Hired to find possible routes linking the crowded East to the growing West, the explorer-turned-campaigner-turned-explorer spent time, energy, and, eventually, lives looking for a perfect railroad route across the West. His fourth expedition ended in chaos and cannibalism after becoming stranded in the snowy San Juan Mountains. Ten men succumbed to the elements and Ute attacks.

After a brief sideline as one of California’s Senators, his fifth and final expedition was more successful. He discovered a plausible winter railroad route over the Rockies at Cochetopa Pass.

But it was all for naught. The eventual Transcontinental railroad ended up running along a more northerly route through a pass in Wyoming.

Unfazed and still as popular as ever, Fremont was tapped as the young Republican party’s first national candidate in the 1856 presidential elections. An abolitionist in the vein of the party’s more radical members, the adventurer ran under the slogan “Free Soil, Free Men, and Fremont,” which is pretty catchy even by modern standards.

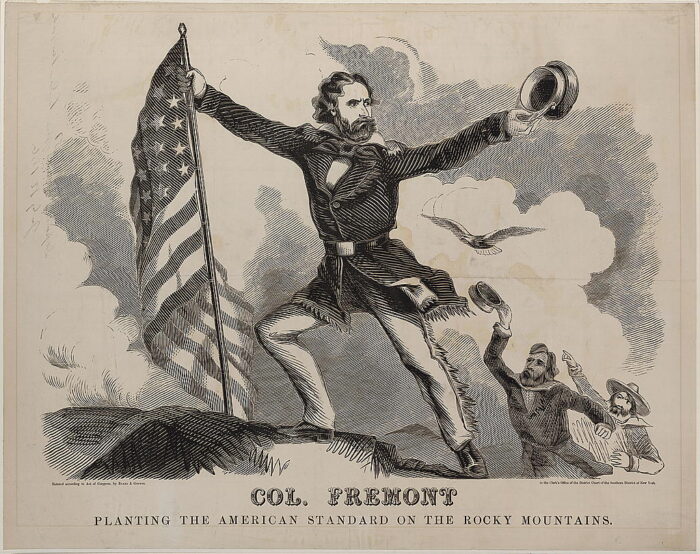

A campaign poster for the 1856 presidential elections. Illustration: Wikimedia Commons

Failed candidate

However, national politics weren’t ready for such a radical stance. Despite widespread popularity as the Pathfinder, Fremont lost to Democratic candidate James Buchanan. It would take a more centrist candidate by the name of Abraham Lincoln to win the burgeoning Republican party its first presidency in 1860.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Lincoln tapped Fremont for a Major General position in the Union Army. Fremont was a middling general whose most noteworthy wartime accomplishment wasn’t a major victory or brilliant troop movements but a bucking of authority that once again landed him in hot water.

On Aug. 30, 1861, Fremont (without notifying the President) placed Missouri under martial law and unilaterally decreed that all slaves in the state were emancipated. Students of history will remember that Lincoln didn’t issue his own emancipation proclamation until almost a year later. Lincoln was weighing the policy heavily and carefully and slow-walking it so as to avoid losing more border states to succession. He swiftly ordered Fremont to walk back the order, which the stubborn Fremont predictably refused to do.

Lincoln sacks Fremont

Lincoln then removed Fremont from command. However, given the pressing need for capable leaders, it wasn’t long before Fremont was once again charging into battle in Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Organizational changes in 1864 prompted his final resignation from military life.

Fremont spent the rest of his days battling financial difficulties caused, at least in part, by his resistance to authority. For example, a brief stint as the Governor of the Arizona Territory ended when the cantankerous explorer refused to actually govern from the territory itself. Ultimately, the family relied upon publishing income generated by the always-resourceful Jessie. Fremont died in 1890 at the age of 77.

Fremont in the last years of his life. Illustration: Wikimedia Commons

A complex legacy

Fremont is both a revered and controversial figure. There is no doubt that Fremont was crucial to westward expansion. He pioneered the way for settlers through hard work and an idealized vision of American progress.

Today, the city of Fremont near Sacramento, California and the famous Fremont Street in Las Vegas are named after him. Los Angeles has a John C. Fremont High School. His name features on many places across the U.S. There’s no escaping his legacy.

At the same time, he exposed the flaws of such idealization while crippling his own career through a stubborn adherence to his complicated morality.