In the 19th century, biology, physics, chemistry, archaeology, geology, geography, and paleontology took off like a rocket, as did social fields like psychology and anthropology.

Unfortunately, many researchers used anthropological research — and pseudo-sciences like phrenology — to make a case for the racial biases of the era. You don’t have to dig too deeply into the scientific literature of the 1800s to unearth treatises by learned men written in favor of slavery, forced labor, and colonialism.

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay, perhaps the most likable 19th-century explorer you’ve never heard of, stands in stark contrast to this trend.

A small monument to Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay overlooks a bay in Papua New Guinea.

As an ethnologist, anthropologist, and biologist working primarily in Australia, the Philippines, and Papua in the late 1800s, Miklouho-Maclay spent years living among the native populations of those regions. His refreshingly open-minded personality and physical hardness allowed him to conduct research in environments that were difficult and even dangerous to white explorers. During his work, Miklouho-Maclay developed an outspoken and passionate hatred of slavery and other human rights abuses.

Had he dodged the cancer that removed him from the mortal coil at the too-early age of 41, the Russian-born scientist might have done more to end the poisonous treatment that European colonial governments inflicted on the natives of Oceania. But Miklouho-Maclay accomplished much with the time given him, and he is still favorably remembered by many in the region.

But perhaps not as well as he should be.

A rule-breaker from the start

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay was born in the Russian Empire in 1846. Miklouho-Maclay’s father, Mykola Myklukha, was made of the same stern stuff he apparently passed on to his son.

One example: After graduating from school in the Ukrainian town of Nizhyn, Mykola Myklukha walked over 1,000km to St. Petersburg to enroll in engineering school. Myklukha also possessed a rebellious spirit. Shortly before his death, he was fired from his job on the Moscow–Saint Petersburg Railway for sending a small amount of money to a Ukrainian poet exiled for criticizing Russian treatment of Ukrainians.

This inherited rebellious streak emerged throughout his son Miklouho-Maclay’s early life. In 1863, 17-year-old Miklouho-Maclay was arrested for participating in student protests. Only timely intervention from friend-of-the-family Leo Tolstoy saved the young man and his friends from extended prison time, or worse.

Undaunted, Miklouho-Maclay audited classes at the University of St. Petersberg before being expelled for “breaking the rules” (what, exactly, he did is lost to us.) The budding scientist promptly forged a passport and made his way to Germany.

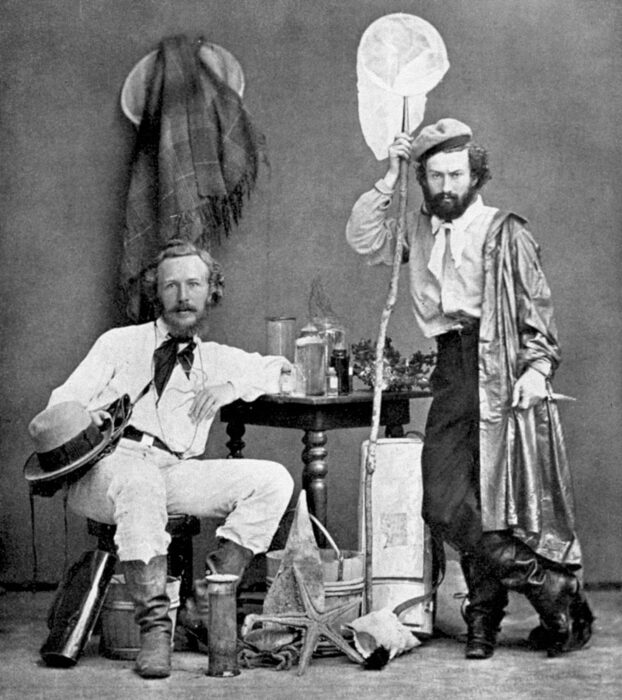

Miklouho-Maclay, right, and his mentor, Ernst Haeckel, pose for a photograph while on an expedition in the Canary Islands. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A varied education

It’s hard to know if Miklouho-Maclay already knew how he wanted to spend the rest of his life. Still, his broad and varied education in German universities couldn’t have prepared him better for life as an explorer-scientist. He studied medicine, humanities, and zoology at various German schools, eventually landing under the tutelage of influential scientist Ernst Haeckel.

Haeckel took on Miklouho-Maclay as a research assistant on an expedition to the Canary Islands in 1866. There, Miklouho-Maclay studied sharks and other marine life. He managed to describe a new species of sponge during the trip. He named the species Guancha blanca, after the native people who originally occupied the island. The name reflects early respect for Indigenous people, which grew as Miklouho-Maclay’s brief career progressed.

Haeckel was one of Germany’s first proponents of Darwin’s theories, an academic lineage that heavily influenced Miklouho-Maclay once he set off on his own. The young scientist traveled extensively, expanding his skillset, learning languages, and absorbing knowledge from scientists in Europe’s finest museums and universities.

Finally, the lure of adventure was too powerful to resist. Miklouho-Maclay set sail for Australia.

The year was 1871. Miklouho-Maclay’s life was already halfway over.

Oceanic adventures

In Australia, Miklouho-Maclay wasted no time making his mark.

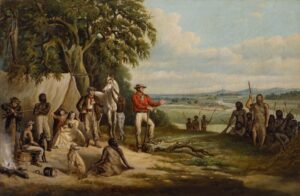

Between 1871 and 1880, Miklouho-Maclay spent years living among the native people of northeastern New Guinea. He also traveled extensively among tribes in Australia, the Malay Peninsula, and the Philippines.

By all accounts, Miklouho-Maclay’s conducted his anthropological studies with respect, humility, and an attitude of mutual aid. His facility with languages, honed by his European travels, allowed him to pick up native tongues. He used his medical skills to assist his subjects whenever possible.

At the same time, he approached his studies without the colonial superiority so common in his contemporaries. Free of this intellectual hangup, Miklouho-Maclay sketched faces, made reams of notes and observations, collected samples, lost samples in shipping accidents, and then recollected them. He rambled over mountains, splashed through swamps, and made maps.

Miklouho-Maclay in 1880, eight years before his death. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

One of his chief accomplishments was the realization that tooth shape among the tribes he studied was a developed trait caused by specific diets and not a racially inherited trait.

Such observations are the through-line of Miklouho-Maclay’s work. He did much to humanize and dispel racist rumors about these tribes at a time when even his fellow scientists mostly viewed the Indigenous people of Oceania as little more than animals.

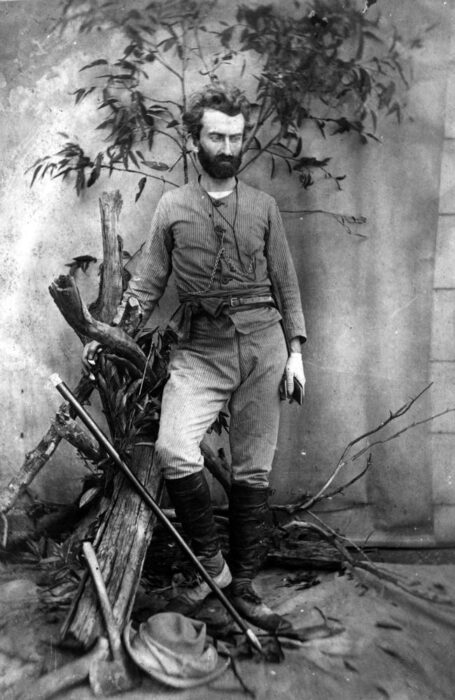

But the research came at a cost. Supply shipments were sketchy at best, and Miklouho-Maclay relied on knowledge gained from his subjects to supplement his meager rations. He also suffered from recurring bouts of malaria. These privations are visible in contemporaneous photographs, which reveal a haggard, bearded face and a rail-thin physique.

Anti-slavery activism

When he wasn’t living rough in the bush, Miklouho-Maclay was attending to a legacy that would long outlive him.

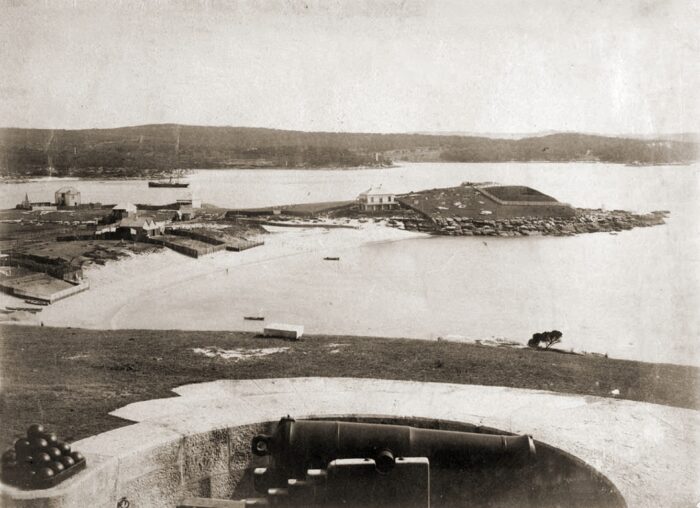

The increasingly influential scientist proposed the construction of a biological research station, and his scheme was eventually accepted. The Marine Biological Station outside of Sydney, Australia, became the first scientific research station in the Southern Hemisphere. While researching there between field studies, Miklouho-Maclay managed to describe a new species of wallaby and began research on the hibernation patterns of echidnas.

Miklouho-Maclay oversaw the construction of the Marine Biological Station outside of Sydney, Australia and also conducted research there. But his heart was in the field.

But Miklouho-Maclay was too restless to spend his hours in a (relatively) comfortable research station. He returned again and again to the life of an explorer-scientist, and his research eventually led to abolitionist activism almost unheard of among academics of the day.

While in the field, Miklouho-Maclay made a point of warning his subjects against the illegal slave traffickers that preyed upon the coasts. He also intervened in the trial of Indigenous people accused of murdering white missionaries, attempting to bring cultural understanding and empathy to a fraught situation.

From the research station, he wrote scores of passionate and eloquent letters and articles denouncing slavery, land grabs, arms trading, liquor importation, and other degradations foisted upon Indigenous people by European colonial governments and white settlers.

His words moved the needle. In 1878, the Dutch government agreed to crack down on slave trafficking on the twin Indonesian islands of Ternate and Tidore.

Final years

The last few precious years of Miklouho-Maclay’s life were marked with ill-health. It’s unclear when the undiagnosed brain tumor that would eventually kill him began to develop. In any case, it’s certain that a decade of rough living and malaria took its toll.

Nevertheless, the always restless scientist spent the years between 1879 and 1888 traveling back and forth from Russia, where he lectured at the Russian Geographical Society — quite a glow-up for a man once kicked out of multiple educational institutions.

Along the way, he managed to get married to the daughter of the premier of New South Wales.

Miklouho-Maclay’s health took a turn for the worse in 1888, and he died in his wife’s arms in April of that year. His copious notes and observations were a boon to anthropologists for decades to come. But it’s his eminently humanist approach to anthropological research that stands him out from his contemporaries.

As this humble journalist can’t possibly outwrite Tolstoy, I’ll let a letter from the great Russian scribe finish speaking to Miklouho-Maclay’s legacy.

“You were the first to demonstrate beyond question by your experience that man is man everywhere, that is, a kind, sociable being with whom communication can and should be established through kindness and truth, not guns and spirits,” Tolstoy wrote to Miklouho-Maclay in 1886.

“I do not know what contribution your collections and discoveries will make to the science for which you serve, but your experience of contacting the primitive peoples will make an epoch in the science for which I serve, i.e. the science which teaches how human beings should live with one another.”