“From here to Timbuktu!” This popular saying is synonymous with traveling into the unknown. Over the centuries, the iconic Malian city earned a reputation for being exotic, mysterious, far-flung, and sometimes dangerous. For most explorers, the region was inaccessible because of its hostile climate, suspicious (and often hostile) people, and general unpredictability.

Ambitious Frenchman Rene Caillie aimed to be the first European to explore the city and return alive.

Rene Caillie’s early life

Caillie grew up a “nobody” in the 19th century. His father was a baker and a felon who served jail time in a penal colony. When Caillie was 12, his mother died, and he and his sister were orphaned. Orphaned children were depressingly common at the time and many young boys took to the seas, working on ships for months and sometimes years at a time.

At age 16, Caillie began to dream of traveling the world and exploring exotic cultures. “The History of Robinson Crusoe, in particular, inflamed my young imagination…Geographical books and maps were lent to me. The map of Africa, in which I saw scarcely any but countries marked as desert or unknown, excited my attention more than any other,” he later wrote.

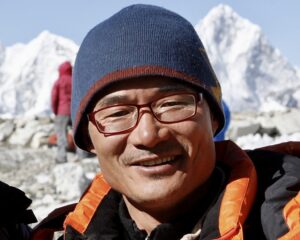

Rene Caillie portrait. Photo: Amelie Legrand de Saint-Aubin

Caillie joined the crew of the ship Meduse, on course for Saint-Louis in Senegal. But the voyage was a disaster and the ship was wrecked off the coast of Mauritania. Caillie and a few others survived and continued to Dakar.

The people, traditions, and landscape in Senegal enthralled him, but he wanted to explore the interior. His first expedition attempt failed because of sickness brought on by dehydration and exhaustion.

He returned to Senegal a couple of times, with ambitions to explore Timbuktu. At the time, it was one of the last “undiscovered” locations in Africa. It supposedly possessed immense wealth and some considered it Africa’s El Dorado.

Timbuktu, the final frontier

Records of Europeans venturing to the Malian city date back to the 16th century. Based on the writings of Leo Africanus, a North African scholar from the 1500s who set foot in the city, Europeans who dared to travel to Timbuktu didn’t know what they were getting into. The city was a rich learning hub, wealthy from gold and salt mining, culturally diverse, and a valuable trading center for merchants. Salt was the city’s most important export.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, stories of (mostly failed) expeditions started to pop up. In 1799 a British group including Scotsman Mungo Park was charting the Niger River. Park was supposedly the first Westerner to reach Timbuktu, but he died shortly after from an unknown cause.

In 1812, American seaman Robert Adams controversially claimed that he was held captive and had seen the city. However, his story is disregarded by academics.

A dangerous ambition

Europeans who tried to gain access to Timbuktu tended to turn up dead. Before Caillie, Major Gordon Laing had attempted to reach the city and was murdered. But Caillie was confident. He successfully applied for funding from the Societe de Geographie to become the first European to visit Timbuktu and return alive.

Caillie disguised himself as an Arab and converted to Islam so he could travel safely. He stayed in Sierra Leone and Boke in Guinea where he learned local languages, the laws of the land, and traditions. He convinced locals that he was a poor Egyptian trying to make his way back home after the French captured him.

But Caillie frequently contracted diseases. He caught scurvy, dogs attacked him, and he suffered in the hot weather. Despite the challenges, he remained optimistic and forward-thinking.

He eventually reached Timbuktu, describing it as “incredibly imposing.” According to writer Larry Brook, Caillie had a bit of a false start when he arrived. Brook recounts how Caillie mistook the city for a city of gold because of its beautiful glow in the sunset. He awoke the next day to a “mass of ill-looking houses, built of earth.”

Caillie noted how slaves were treated very well in the city, dressed in fine clothing, and donned jewelry and gold. He tried local cuisine and visited the main mosque. But he remained very ill.

He spent two weeks in Timbuktu before leaving with a caravan to Morocco. However, his health continued to suffer and he eventually contacted a French embassy to secure passage back to France. There, he received an award for his adventures in Africa. The French government gave him 10,000 francs and the Cross of the Legion of Honour.

Galbraith Welch published an extremely detailed account of Caillie’s expedition to Timbuktu in the book The Unveiling of Timbuctoo: The Astounding Adventures of Rene Caillie.

Timbuktu in Mali. Photo: Shutterstock

Conclusion

Caillie’s journey to Timbuktu was an impressive endeavor, particularly solo. He was strategic, flexible, and resourceful. He took a more progressive approach than other Europeans attempting to reach the city, going to impressive lengths to get there without military force. Instead, Caillie immersed himself in the land and its people and was rewarded as perhaps the first European to visit the city and return alive.