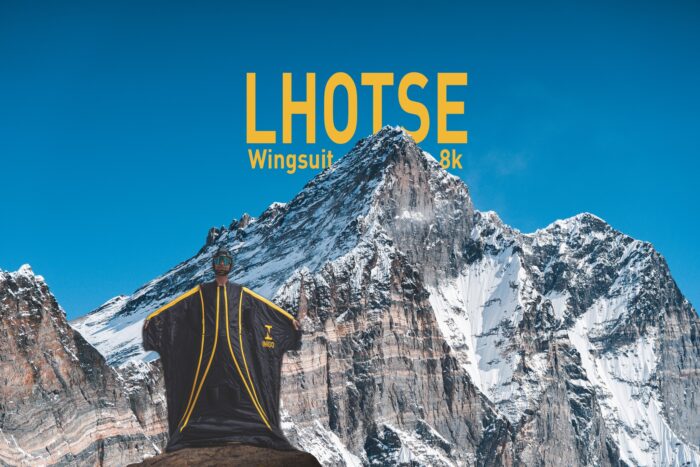

Tim Howell of the UK is currently one of hundreds trekking to Everest Base Camp. But after he arrives, he will attempt something unique: the highest wingsuit jump ever.

He does not intend merely to set the current record, but one that will stand forever.

“Once Lhotse has been jumped [from the exit point Howell has in mind], there will be no higher place on Earth to jump from,” he told ExplorersWeb.

Background

Twelve years ago, Tim Howell was a young climber on big walls in the Alps and the United States. Sometimes, he saw BASE jumpers plunging off the cliffs he had just climbed. He started skydiving on his 23rd birthday. Two years later, he did his first BASE jump.

“It was sort of a logical progression,” he told ExplorersWeb.

“Then I started to add my climbing skills to my BASE jumping. The result was a seven-year project to climb and BASE jump the six so-called Great North Faces of the Alps,” he recalled.

Howell launches into the void. Photo: Facebook

Howell indeed became the first to climb and wingsuit jump from the North Face of the Eiger, the Matterhorn, the Tre Cime di Lavaredo, the Grandes Jorasses, the Dru, and Piz Badile. All the while, he served in the Royal Marines.

Eventually, he quit the military to live as a full-time climber and wingsuit BASE jumper. Soon, he wanted to broaden his horizons and jump in places where no one had before. He went to Kenya, Vietnam, and Argentina. Two seasons ago, he jumped from above 6,000m on Aconcagua (check the video below). It was his personal altitude record and the first time someone with a wingsuit jumped from the South American peak. Logically, the Himalaya came next.

Why Lhotse?

“I have looked at all 14 8,000’ers and their potential exit points, looking both for the highest possible and at the same time, accessible,” Howell explained.

At first, the perfect place seemed to be Cho Oyu, at 7,800m and very close to the normal route. However, Russian wingsuit altitude pioneer Valeri Rozov had already done it.

“I wanted to break his record, so I had to look higher exit points, with a cliff long and vertical enough to launch a wingsuit jump from,” Howell said. “That only left Lhotse.”

Howell scouted the area in a helicopter last November and found a suitable exit point on the ridge. “Once I have jumped from it, there may not be a higher place to jump from,” he said.

From Howell’s Facebook page.

Unlike paragliding flights, BASE jumps begin from a vertical exit point with no glide until the jumper builds up speed. So wingsuiters need a high vertical cliff and enough clearance to spread their winged arms. This is why, Howell explains, the summit of Everest is not suitable. Lhotse, on the other hand, has its enormous South Face, one of the biggest walls on Earth at 3,300m.

“The limiting factor on Lhotse is access,” Howell said.

Indeed, the long ridge separating Lhotse and Everest has never been fully climbed. Only a handful have dared to reach the ridge’s most outstanding points. Howell’s planned exit point is some 500m down the ridge from the summit, at approximately 8,100m.

The jump comes first

The pilot is also clear that his goal is the jump, not the climb. “A weather window for a wingsuit jump is not as simple as a summit window,” says Howell. “It’s not about just reaching the summit and then jumping. It may mean multiple summit attempts, and I need to keep myself as fit, healthy, and clear-minded as possible.”

So Howell will rely on supplemental oxygen as needed, and three climbing sherpas and UK guide Jon Gupta will support him. Gupta is back in the Himalaya after a two-year break to focus on the Alps.

In addition to thin air, the main factor in such a high-altitude jump is the wind. Wind that’s too fast, unstable, or from the wrong direction may be fatal.

“That is why we’re giving ourselves enough time, oxygen, and resources so that we can remain at altitude for quite some time,” Howell said.

He wants to be able to stay at Camp 4 as long as necessary, even if it means going to the ridge and back several times until conditions are right. Howell said the wind was perfect during the helicopter reconnaissance last fall. He is confident he can find a similar situation in the spring.

From Tim Howell’s Facebook feed.

Landing plans

Howell will use oxygen on the mountain but he will jump without it. It makes sense. After all, he’ll get down to 4,000m to 5,000m within a couple of minutes, courtesy of gravity.

Howell’s wingsuit has been specially modified for this jump. It is down-filled, but not too thick.

“Instead, I’ll haveextra down pants and a jacket that I will take off for the flight,” Howell said.

He will also wear heated shoes and gloves. On his jumps in the Alps, Howell flew with the rope and climbing gear on his back, but here, he wants to fly as light as possible. He’ll use ultralight gear and carry only what he needs after landing.

Howell points out that the wingsuit jump requires a big enough cliff — no problem on Lhotse — and a suitable direction. Here, the direction is southwest toward Chukhung village, at 4,730m. “I have several potential landing spots in mind, depending on my glide ratio, but hopefully I will get as far as Chukhung.”

Chukhung village location (bottom center), compared to the Everest-Lhotse group. Photo: Google Maps

No competitors

No one has jumped from Lhotse before. Nor from Everest, although Valery Rozov, considered one of the pioneers of BASE jumping at high altitude, is sometimes erroneously said to have done so. In fact, he jumped from Changtse, the northern peak of Everest on the Tibet side, from an altitude of 7,220m. Then in 2016, he jumped from 7,700m on Cho Oyu. Rozov died one year later while jumping from Ama Dablam.

Not many have tried since then. “The technology is still basically the same,” says Howell. “What has changed is people’s knowledge and experience.”

What it takes to BASE jump at high altitude

“A wingsuit needs time to pressurize and only then do you start getting forward momentum,” Howell explained. “At a normal altitude, it takes me about 200m to really start getting forward momentum. On Aconcagua, it took me 300m, because the air is thinner and it takes longer for the wingsuit to pressurize. On Lhotse, I am giving myself a margin of error of another hundred meters: I expect it will take 400m.”

Howell notes that there is always a little forward movement, thanks to the jump’s launching push, but while the suit is pressurizing, the glide ratio is about 2.4 meters forward to 1 meter down. “On Lhotse, I’ll give myself a margin of error to compensate for the altitude…I expect to fly at 240kph at least, as I did on Aconcagua [instead of the usual 200kph].”

Tim Howell. Photo: Photo: Tim Howell/Facebook