In 2023, the world consumed more than 7.3 billion kilograms of tea. Bar water, tea is the most popular beverage on earth. We’ve even figured out how to drink it in space, where both boiling water and drinking from a cup is a serious endeavor.

Today, many regions are known for the production and consumption of tea. But for the first few thousand years of its existence, it was synonymous with China.

Tea only reached Europe in the 17th century. When the famous English diarist Samuel Pepys first tried it in 1660, he called it “a cup of tee (a China drink) of which I never had drank before.” He did not record whether he liked it or not. Many British people did take to the drink, though, and by 1800, the Brits were importing 24 million pounds from China every year.

British merchants chafed under the trade deficit; their people wanted tea, silk, porcelain, cotton, and indigo. The Chinese didn’t seem to want anything but silver. To protect their monopoly, the Chinese government made it illegal to sell live tea plants or their seeds, and closely protected the secrets of tea manufacturing. There was only one way around this: The British were going to have to steal tea from China.

![]()

The most powerful company in history

The British East India Company was one of the most powerful and ruthlessly evil corporations ever to exist, and they had set their sights on taking tea from China.

Formed in 1600, Elizabeth I granted the British East India Company (EIC) a monopoly over all trade east of the Cape of Good Hope. The intention was to create a strong, organized merchant army to break Dutch control of the spice trade.

In 1683, Charles II gave the EIC the unilateral ability to “declare peace and war” with the “heathen nations” of Africa, Asia, and America. The EIC had the right to govern colonies, build plantations and military forts, raise armies, and execute martial law within their territories. The private armies of the EIC conquered much of Southeast Asia, ruling India, Pakistan, Burma, and Bangladesh. They turned these countries into wealth-extraction machines, reducing the inhabitants to desperate poverty.

The company controlled the trade of some of the world’s most valuable products: tea, coffee, spices, cotton, silk, porcelain, saltpeter, wool, and slaves. But their monopoly was growing unpopular at home, as it drove up prices and prevented competition. In 1813, the British government opened up trade to India, and in 1833, to China.

But the EIC still had monopolies to trade in a few products, including tea.

This painting depicts a real historical event. Defeated by the army of the EIC, Mughal emperor Shah Alam handed over the legal right to collect taxes in Bengal to Robert Clive, the commander-in-chief of the EIC army. Photo: The British Library

A bold proposition

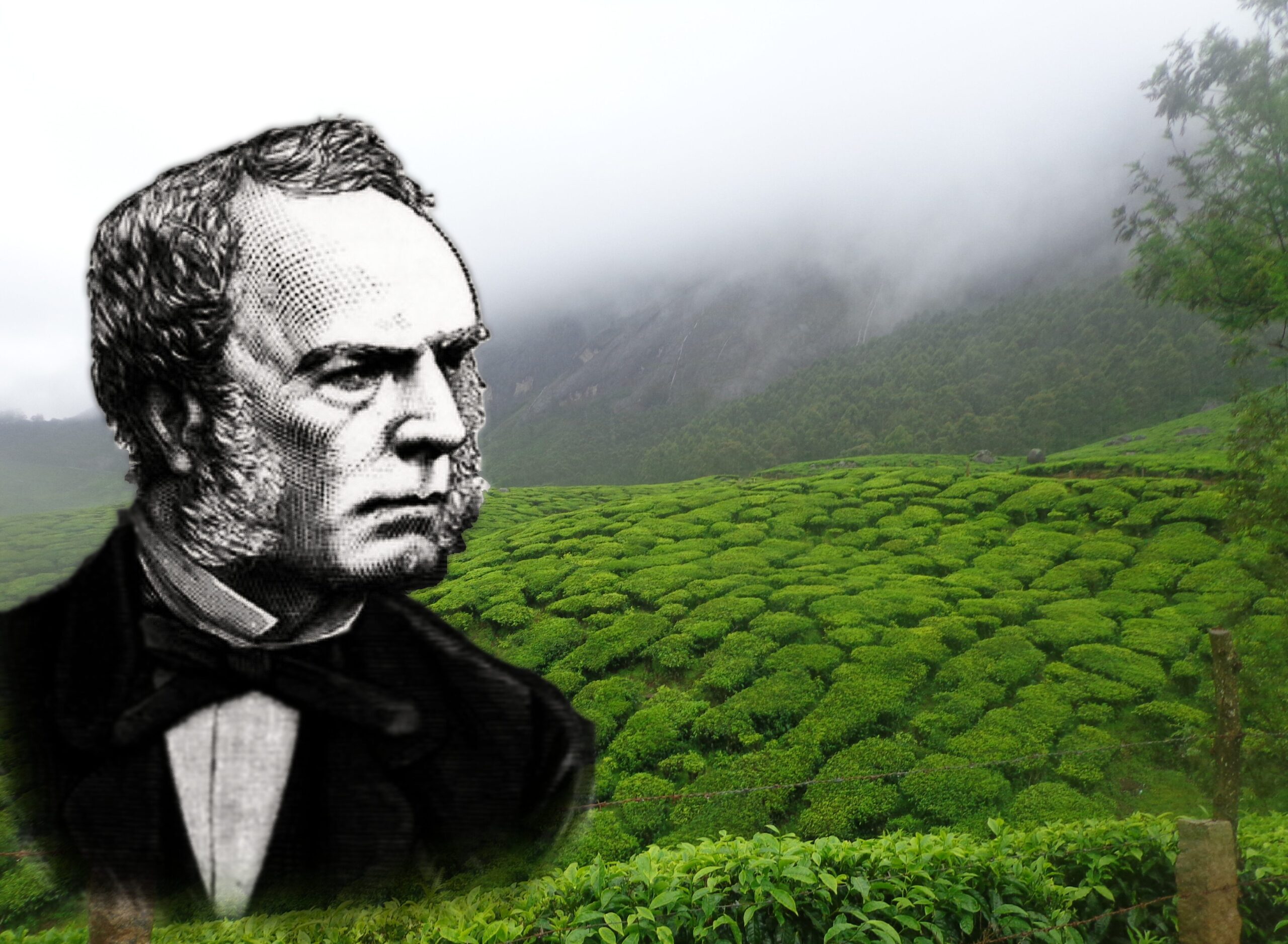

In 1848, Robert Fortune, curator of the Chelsea Physic Garden, was approached by the renowned botanist Dr John Forbes Royle. Royle was an EIC surgeon and the superintendent of the EIC’s botanical garden in Saharanpur, India.

Royle had come to offer him a job, on behalf of his employer. Go to China in disguise, make your way deep into territory never seen by Westerners, and smuggle out living tea plants. Fortune would also need to observe how tea was processed — a closely guarded secret — and make it out of the country with his specimens alive. The pay was £500, five times his current annual salary.

Fortune had already traveled and collected in China, and even observed some parts of the tea growing and collecting process. Before he had gone, many Europeans believed that green tea came from one plant, Thea viridis, and black tea from another, Thea Bohea. Fortune discovered the truth: the difference between green and black tea is in the preparation, not the plant.

Born in Duns, Scotland, in 1812, Fortune came from humble beginnings. He excelled as a gardener on a nearby estate, and in 1839 he moved to Edinburgh to work under William McNab, a celebrated botanist. It was McNab who recommended him to the Royal Horticultural Society in London. The society was sponsoring an expedition to China, allowing Fortune to travel there in 1843.

On that first trip to China, he was attacked by bandits and pirates, battered by typhoons, and nearly killed by fever. He risked death by entering areas banned to foreigners. He also sent back dozens of plants unknown in the West, and brought the art of bonsai to Europe.

In 1848, he agreed to return.

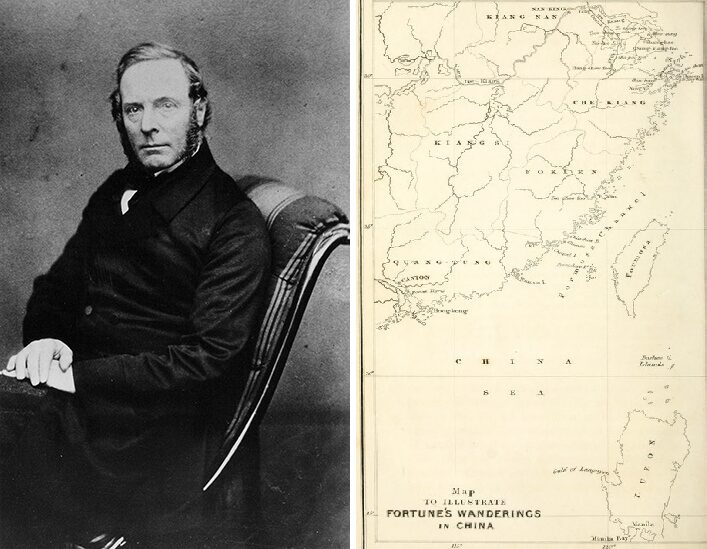

Robert Fortune and a map of his travels during his first trip to East Asia. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Arrival and disguise

On June 20, 1848, Fortune left Southampton on a passenger steamship. On August 14, it anchored in the Bay of Hong Kong. From there, he traveled up the Shanghai River to the city of the same name, then the northernmost open Chinese port.

It had changed since his last visit. In the harbor, Fortune saw “a forest of masts” from English and American ships, and on shore, a Western port town had replaced the Chinese houses and farms. A steady stream of former Shanghai residents poured from the new settlement into the country, bearing coffins. They were retreating with the remains of their ancestors, to rebury them near their new homes.

Fortune didn’t stay long in Shanghai. His destination was the “great green-tea country of Hwuy-chow.” He was referring to famous tea plantations in the Anhui region, deep in the Yellow Mountains. This was where the most celebrated tea was grown, but it was well over 300km from Shanghai, and forbidden to Europeans.

Fortune didn’t trust a Chinese agent to get the samples for him. For one, it would take botanical knowledge to keep the samples alive, and two, he believed that “no dependence can be placed upon the veracity of the Chinese.” Unlike the Chinese, Fortune was honest and forthright, which was why he decided to disguise himself to infiltrate their plantations and steal from them.

Fortune’s hired translator and guide, Wang, rented a boat and found him Chinese clothes. Meanwhile, another servant, a day laborer unnamed by Fortune, shaved his employer’s head into a queue hairstyle. Thus attired, they set off in a riverboat headed inland.

Fortune praised the new English-style gardens of Shanghai. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Discovering devastation

The boat took them upriver to the city of Hangzhou-Fu. On the way, Fortune passed through several large but “dilapidated” cities. Fortune, like many Western men, considered China a great civilization in ruin, whose ancient glory had fallen to stagnation. But there was another reason for the ruined, half-empty towns.

Stealing the secrets of tea was not the first attempt Britain and the EIC made to adjust the trade imbalance. First, they introduced the Chinese to a desirable product of their own: opium.

Opium wasn’t unknown in China, but was used only medicinally. Britain planned to flood the country with the highly addictive drug, forcing Chinese merchants to trade their valuable goods for opium, instead of silver. The EIC could produce opium cheaply in India, and began smuggling it by the ton into China.

A succession of emperors tried to prevent the trade, making it highly illegal, but the drug still got through. In 1838, Chinese officials destroyed over 20,000 chests of opium and set up a naval blockade. British warships fired on them, smashing through and proceeding up the Pearl River. By 1841, they had conquered and occupied Canton, and the First Opium War was in full swing.

A year later, the British took the then-capital city of Nanjing, and the Chinese were forced to sign a treaty handing over the island of Hong Kong and opening new ports. Opium would continue to flow. The effect for many Chinese people was economic depredation, an addiction crisis, and cities ravaged by conquering English armies.

The British East India Company’s steamship ‘Nemesis’ devastated Chinese shipping during the war, destroying dozens of Chinese junks (a type of ship) and capturing a strategic fort. Photo: National Army Museum, UK

Through the gates of Hangzhou-Fu

Fortune had planned to skirt around the outside of Hangzhou-Fu, a large city which sat on the river, on his way from the coast to the tea district. But a miscommunication found him alone in the bustling city, separated from his servants. He believed that if he was detected, an angry mob would tear him to pieces or haul him to court.

Fortunately, his disguise seemed to hold, and Fortune, having decided to hope for the best, stayed in the hired chair his servants had arranged. It took him through the city to an inn where his baggage and his servants were waiting.

It seems difficult to believe that his disguise was effective. Maybe the people around him just didn’t care if he was a foreigner, as long as he was paying handsomely and not causing a disturbance.

However, most of the people Fortune encountered would never have seen a white man before. They also probably hadn’t traveled much outside their district. Fortune did speak Chinese — not fluently, but conversationally — and his errors could be chalked up to a dialect difference. The people he met probably assumed Fortune, going as Sing Wa, was an eccentric, ugly, rich man from a different part of China.

Fortune boarded another river boat, and they glided into the hills. Finally, the river became shallow, and the boat would go no further. As they decamped, Fortune saw Song Luo Mountain, believed to be the birthplace of tea, in the distance.

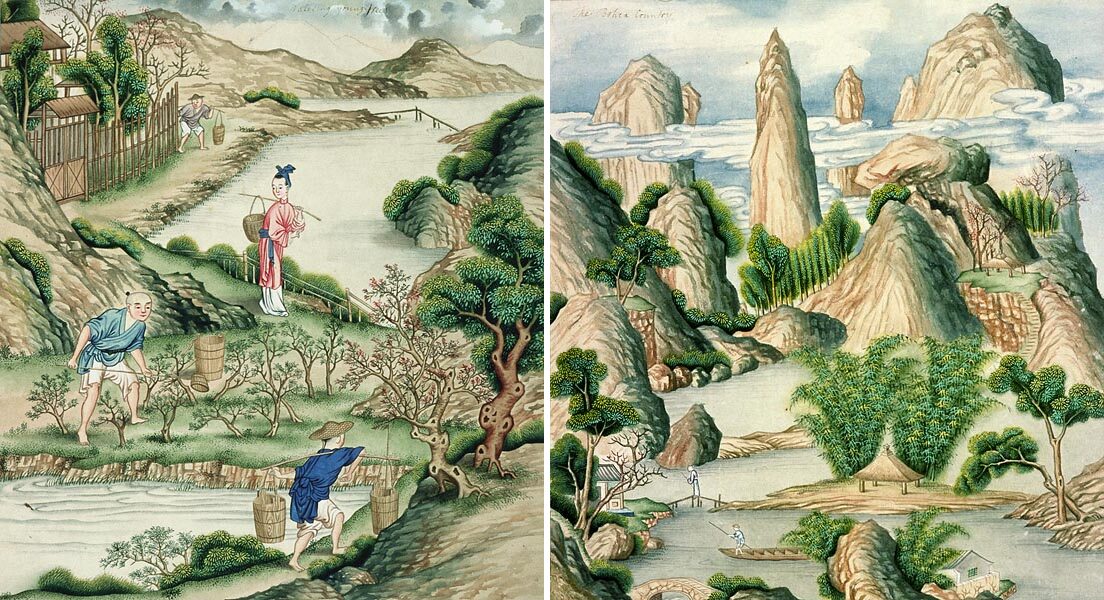

Chinese artists made watercolor paintings of tea harvesting (left) and the tea district, right, for export to Westerners in the 18th and 19th centuries. Photo: Historic Deerfield

Green tea factories and black tea temples

Having reached his destination, Fortune set about recording the climate conditions, soil type, and growing patterns of the lush tea bushes. He recorded, in great detail, how and when the best tea was planted, transplanted, watered, and harvested.

Wang’s father lived in the area, so Fortune, emboldened by success, traveled across the region with Wang’s home as his base. Fortune was able to send many samples back to Shanghai.

But the growing was only half the mystery; how tea is prepared is just as important to its quality. It was Wang who finally got Fortune into a tea factory. He dressed Fortune as a mandarin (a government official) who had come from a distant province to learn about tea manufacture.

The factory supervisor bought the story. Fortune was free to observe the complexities of harvesting, sun-drying, stir-frying, wringing out, stir-frying again, sorting, and packing. Every step is essential to perfecting high-quality tea.

Next, Fortune set his sights on the Wuyi Mountains. Leaving Wang, Fortune hired another guide, Sing-Hoo, who was more familiar with the area. The Wuyi Mountains, then called the Bohea Hills, are the origin of many famous tea varieties today, such as oolong and lapsang souchong.

After a hard climb, they arrived at the top of the mountain at a large temple complex. Sing-Hoo went first, telling the monks that his master, an important man from a far-off region of China, would be staying for a day or two.

It worked. The old priests fed them, gave them a place to rest, and shared wine and tobacco with the visitors. Fortune left with several more living tea plants.

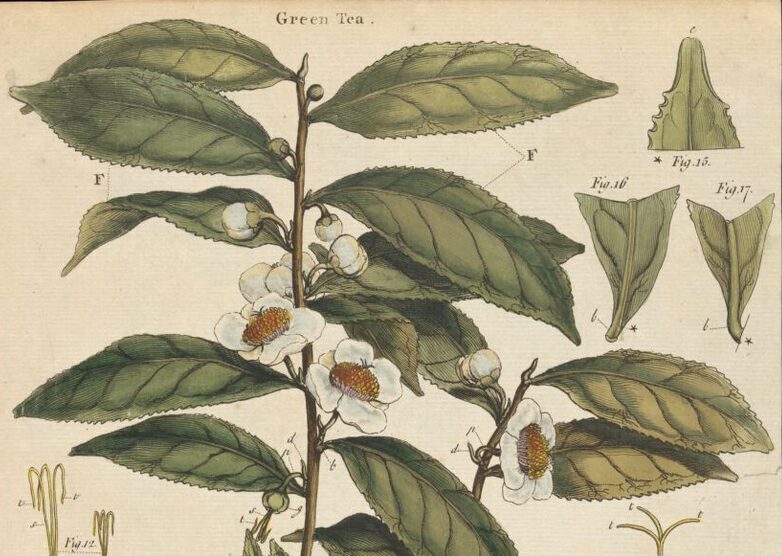

A vintage botanical illustration of a tea plant. Photo: Wellcome Collection

Prussian blue and tea green

Having risked life and limb to penetrate the inner sanctum of tea preparation, Fortune noticed something curious: the workmen’s hands were blue. But only when they were preparing tea for foreign markets; the bulk of tea grown in China stayed in China, and had no associated blueness.

Fortune investigated and found the operation superintendent grinding down gypsum and Prussian blue, a deep blue synthetic pigment, in a mortar and pestle. Workers mixed the resulting light blue powder into the tea leaves. They were dying the tea because most Westerners, to Fortune’s distaste, preferred their green tea to be really green.

Fortune believed tea was best the way the Chinese drank it, without milk or sugar, and certainly without dye. This was a good call on his part; gypsum can produce hydrogen sulfide gas when it breaks down. It also generally acts as an irritant in the body. Don’t eat gypsum.

“It seems perfectly ridiculous that a civilized people should prefer these dyed teas to those of a natural green. No wonder that the Chinese consider the natives of the West to be a race of barbarians,” Fortune wrote.

Fortune secreted away some samples and sent them on to England, where they were displayed to a horrified public.

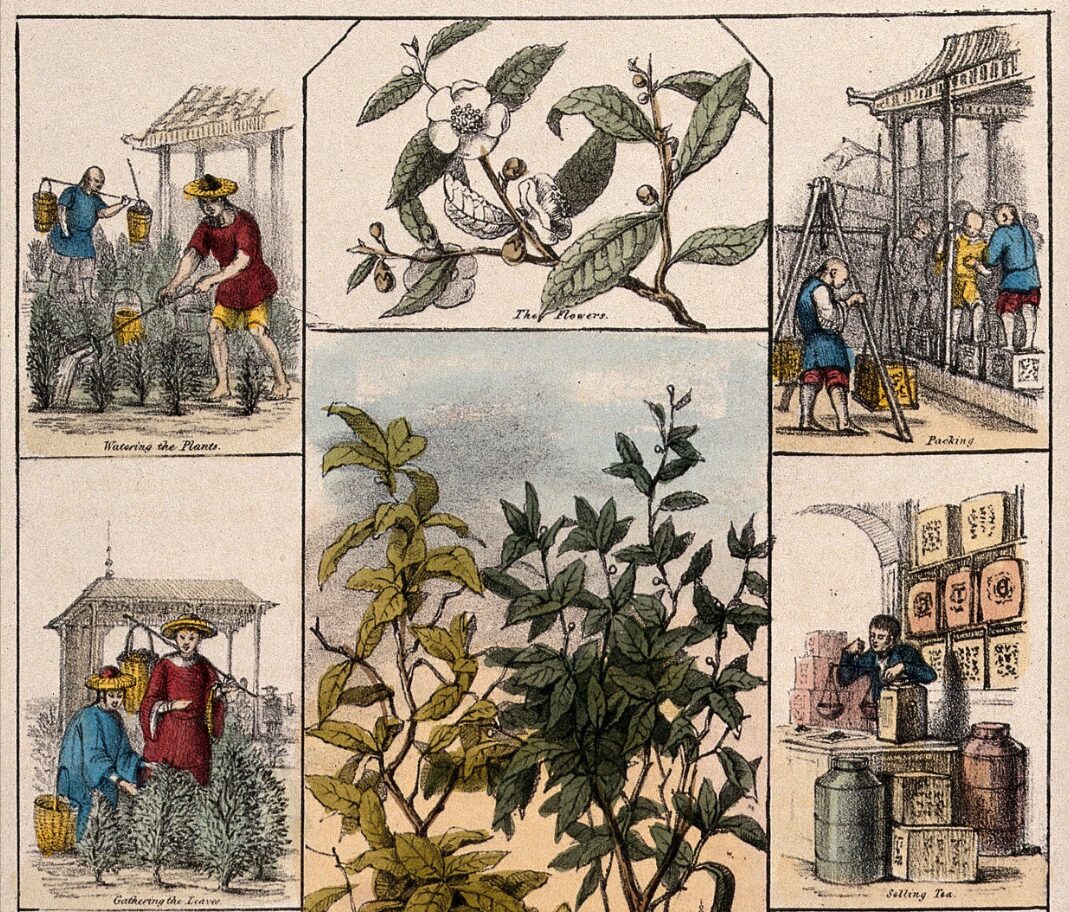

A 19th-century print depicting tea cultivation. The artist does not include the potentially poisonous coloring process. Photo: Wellcome Collection

A Wardian case

Bringing live tea plants out of China and into the Assam region of India presented significant challenges. To keep the little tea plants alive during their long journey, Fortune turned to an ingenious new device: the Wardian case.

Earlier, English doctor and amateur botanist Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward had considered the problem of transporting plants alive. His solution, presented in an 1842 book, was the precursor to the modern terrarium.

He wasn’t the first to discover that plants could be kept alive in a hermetically sealed glass container, but he was the first to publicize it. “Wardian cases,” based on his work, became a trendy item for Victorian drawing rooms. Robert Fortune used them to transport living tea plants from the Yellow Mountains to the foot of the Himalaya.

Ward included numerous case designs in his book, designed for various situations. Photo: New York Botanical Garden Library

Tea takes root in India

India already had a type of tea, growing wild and cultivated for medicinal use. But the British didn’t want that; they wanted the tea from China, but for far less than what the Chinese charged them. They started plantations in Assam, awaiting the tea seeds and plants from China.

As a result of Fortune’s mission, nearly 20,000 tea bushes were planted in India. He also hired skilled Chinese tea growers to lead production. Fortune wrote of the new tea plantations with pride, believing they not only provided cheap tea to the English but gave employment opportunities to Indians.

“If part of these lands produced tea, [a rural Indian man] would have the means of making himself and his family more comfortable and more happy,” Fortune wrote optimistically.

British dominion did not make rural Indians more comfortable and happy, but it did make India a tea-producing country.

Today, Assam is the world’s single largest tea-growing region. India as a whole is the second largest tea producer after China, exporting over 250 million kilograms annually. I’m drinking tea as I finish writing this article. I checked the packaging; it was grown in Assam.