Australia was, for many decades, the open-air prison of Britain’s criminals. Most were convicted of petty offenses. A quick perusal through the records finds convicts transported for stealing a coat, lying in court, impersonating a Royal Navy sailor, and poaching.

Once arrived, the convicts, mostly young men, were put to work. Their purpose was to provide the raw labor that British interests required to transform Australia into a machine for resource extraction. Building infrastructure, establishing large-scale agriculture, and killing, pushing out, or enslaving the native inhabitants.

Through this system, the convicts, themselves the victims of British imperial violence, often ended up being some of the most vicious perpetrators of that violence against the Aboriginal Australians. Some convicts, however, escaped and found shelter, solidarity, and even family among the Indigenous groups they’d been pitted against.

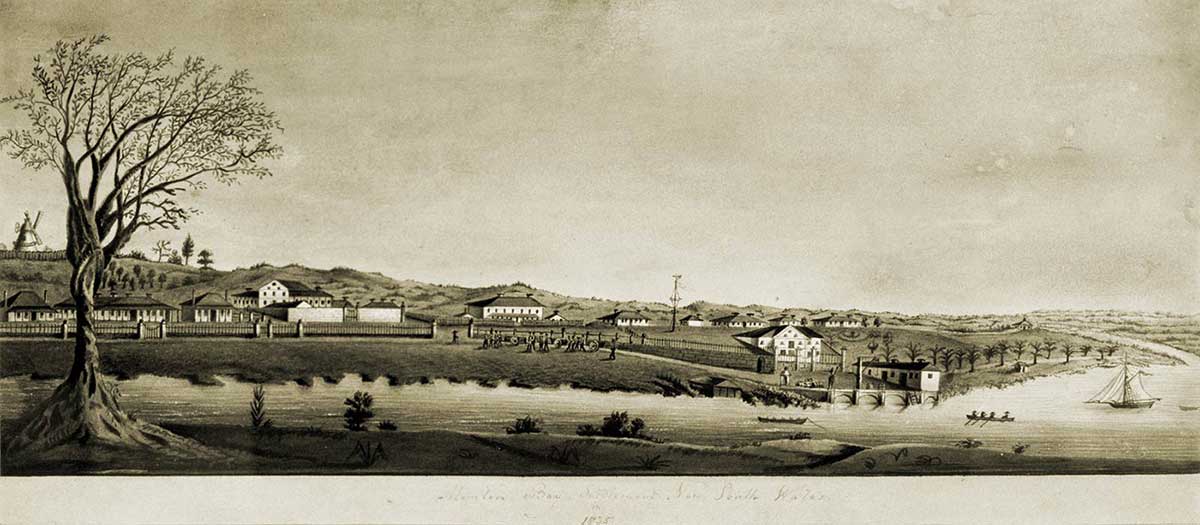

The Moreton Bay penal settlement, circa 1835. Photo: State Library of Queensland

From Moreton Bay to K’gari

During the first half of the 19th century, an unexpected relationship emerged between the Moreton Bay convict settlement and the people of K’gari Island and the surrounding coastal region.

Moreton Bay, in what is now Queensland, was the “maximum security” facility of the eastern Australian penal system. Convicts who had committed another crime while in another penal colony, including attempting escape, were shipped to Moreton Bay. There, conditions were brutal and punishment severe. One in ten convicts died in 1828-1829 alone.

K’gari Island, just a few days’ walk up the coast, is the world’s largest sand island. In the early 19th century, it was one of Australia’s largest Indigenous population centers. Several thousand inhabitants lived on the island and in the surrounding coastal areas. The primary group was the Butchulla, with the Kabi Kabi people occupying the coast between Moreton Bay and the K’Gari area.

Brutal conditions in Moreton Bay led many to escape, becoming “absconders.” Some absconders were quickly caught, while others failed to survive in the wild. But some, with local help, stayed free for years, and even avoided recapture forever.

The absconders’ gamble

Running was a desperate act. There were no white settlements for many hundreds of kilometers, and surviving alone in the bush took incredible skill, physical endurance, and luck. Recaptured absconders faced severe punishment.

Nevertheless, many did run. John Sterry Baker and George Mitchell achieved one of the first successful abscondings. They fled Moreton Bay on Jan. 8, 1826.

They soon split up. Mitchell went north, where he met another convict — more on him later — and lived with the support of a Kabi Kabi headman, Ngumundi. After several years, word reached him that he’d actually been pardoned, and he returned.

John Baker was a 27-year-old who was sent to Moreton Bay for stealing a sheep. Baker fled inland, following a tributary of the Brisbane River. There, he almost died of exposure and starvation. Luckily, a group of Aboriginal people found Baker.

A local group found Baker by a creek in the bush, struggling to survive. Photo: Public Domain

They recognized him, in fact — to his surprise, they claimed he was a deceased friend of theirs named Boraltchou. He said he didn’t think that he was, but between his dire state and the language barrier, he eventually found it prudent to go along with them. In fact, he went along with the story for the next 14 years.

He learned their languages and customs, explored the region, and lived as Boraltchou until August of 1840. He reappeared at Moreton Bay, which by then was in the process of decommissioning. Instead of punishment, he got a job offer — interpreter — and worked in Sydney until his death in 1860.

Ghosts and kinsmen

John Baker was not the only misplaced white man who was adopted as a deceased Aboriginal person. Some groups in the Queensland region practiced mortuary flaying, carefully removing the skin of their deceased loved ones as a way to care for their body. This process would leave the white fascia visible, resulting in white corpses.

This may be why, when they saw a pale stranger near death, the people Baker met assumed he was a spirit returned. But the belief in loved ones returning as white-skinned corporeal spirits extended beyond Queensland.

The Kaurareg people of the Torres Strait called returned, white-skinned spirits markai. When a shipwrecked Scottish teenager named Barbara Thompson washed up on Prince of Wales Island, a local community leader recognized her as his deceased daughter, Giom. She lived as the markai Giom for five years before leaving on a passing British survey ship.

As the years went on, the understanding of white strangers as literal ghosts may have given way to the white-ghost designation as a shorthand for a certain type of person, and a way of understanding how they could fit into a community. Literal or figurative, the belief in white-faced returning spirits was a boon for many shipwrecked or absconded Europeans in the early 19th century.

HMS Rattlesnake, the survey ship that picked up Barbara Thompson in 1849, was exploring the region when it happened to pass Thompson’s island. Photo: National Maritime Museum, London

A mutinous, very bad fellow

David Bracewell was a 23-year-old sailor of somewhat rough character. When he was arrested in 1826 for “assault with intent to rob,” his records note that he’d been in jail before. His recidivism landed him a sentence of 14 years. The transport ship records state that he was mutinous and a “very bad fellow.” He didn’t impress the authorities once in Australia, either. Bracewell arrived in Hobart Town in June and was in Moreton Bay by December.

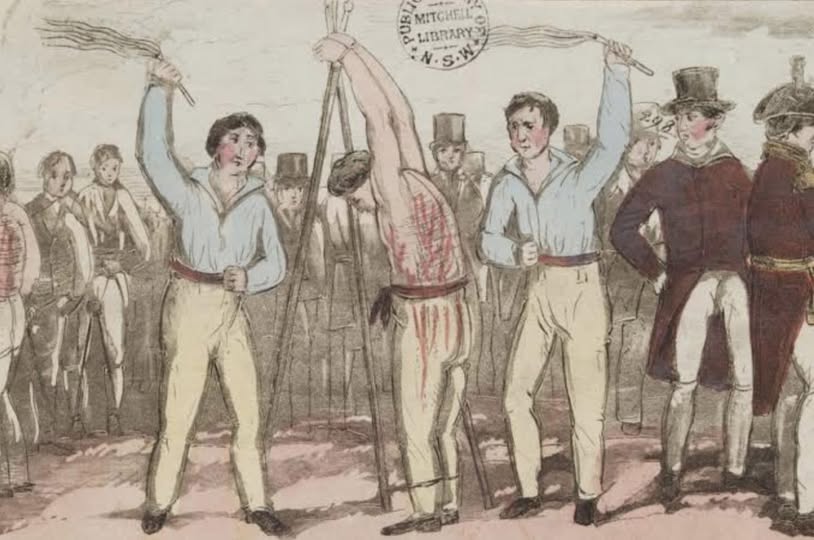

He absconded that spring, and after they caught him, authorities gave him 150 lashes. In 1828, 1829, and 1831 he absconded again, finally managing the final time to avoid recapture. For six years, he was free, traveling and falling in with various Indigenous groups.

In 1837, a Naval party entered Kabi Kabi land by the Noosa River mouth, looking for a rumored shipwreck. Instead, they heard a rumor of an escaped convict. One of the men in the party was a convict named Samuel Derrington. Derrington went into the bush and emerged with Bracewell in tow, earning £5 and a year off his sentence. Bracewell was shipped back to Moreton Bay.

In 1839, he absconded again. You have to admire his persistence. He ended up in the Wide Bay area, where he joined a Kabi Kabi tribe. Their prominent headman was Ngumundi, who had been George Mitchell’s savior 13 years earlier. Ngumundi adopted him and named him Wandi, meaning “big talker” or “great talker.”

The man who had Bracewell, and many others, flogged was the notorious commander of the Moreton Bay penal settlement, Patrick Logan. When he was killed by Aboriginal people in the bush in 1830, there was general rejoicing in Moreton Bay. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

If you want to catch an absconder

Samuel Derrington, who apprehended Bracewell in 1837, was himself a former runaway. Convicted of burglary in 1826, Derrington had fled a life sentence in Moreton Bay in late 1827. He returned in 1836 with an incredible — I may even say unbelievable — account of his years away.

According to Derrington, he was held captive by a tribe living on the coast of Queensland. His obituary claims that Derrington “was especially the object of female vigilance.” Despite not being allowed to leave, he somehow became chief and led his people to glorious victory against nearby enemies.

Chief/prisoner or no, he did learn several local languages of the Kabi Kabi family as well as the customs of the region. When he returned in 1836, he offered his skills as bushman and interpreter in the hopes of reducing his remaining sentence. His jailers first tested him as part of the party that located Bracewell.

The leader, a Lieutenant Otter, gave Derrington a good review. So a few months later, when news of another wreck reached the settlement, they sent Derrington along. The party heard that the four survivors had been killed in a conflict with the locals, somewhere out in the bush. Derrington again set out.

According to a letter from the Moreton Bay commander to the Colonial Secretary, Derrington “quitted the party alone, and entirely naked, and having traveled in this manner about thirty miles through the forest, making enquiries, rejoined the party with intelligence, which partly led to the discovery of the murdered bodies.”

This was enough to get him his ticket of leave. Derrington moved to East Maitland, married, and became a successful tinsmith.

Hundreds of prisoners at Moreton Bay lived in these barracks. Photo: Queensland State Archives

Elisa Fraser on K’Gari

The fraud of Elisa Fraser is too tangled to properly cover here. But to strip the story to the essentials: In May of 1836, the brig Stirling Castle sank off K’Gari. The 11 survivors, including Captain Fraser and his wife, Elisa, were taken in by the resident Butchulla. At least, that’s the story that other survivors and Butchulla oral records tell.

According to Elisa, she was cruelly held captive and forced into brutal labor and mistreatment after the death of her husband. In fact, the work she was asked to do was normal domestic labor for Butchulla women. The Butchulla had no reason to hold someone captive who wasn’t particularly helpful and was, according to their oral telling, considered mad.

Whatever the truth, Fraser was certainly looking to leave K’Gari. Her chances seemed low, but rumors of the Stirling Castle wreck had reached Moreton Bay. Lieutenant Otter organized another search party, which sallied forth into the bush, guided by a convict volunteer named John Graham.

K’Gari Island, off the coast of modern-day Queensland. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The convict scouts of the Elisa Fraser ‘rescue’

A young Irishman convicted of stealing six-and-a-quarter pounds of hemp, John Graham was sent to work for a mill owner in Parramatta. There, he met and befriended some of the local Dharug people, who taught him their language and their fishing and foraging techniques. After only a few years, though, he was caught for petty theft and sent to Moreton Bay.

John Graham ran from Moreton Bay in July 1827 and stayed out until 1833. During this six-and-a-half-year span, he met up with George Mitchell (remember, Ngumundi’s protegé from earlier). Graham abandoned his initial plan (find a boat and sail to China, somehow) when an Aboriginal woman recognized him as her late husband. She eventually died, but Graham stayed with the tribe, learning their language and way of life.

By 1836, though, he was back in Moreton Bay, serving his original sentence plus the time he’d been away. He volunteered for Otter’s expedition, hoping to win a reduced sentence. Graham went unarmed into the bush and made contact with the Butchulla, negotiating for the handover of the three surviving crewmen and Elisa Fraser. According to Otter, Graham “shunned neither danger nor fatigue,” and without his help, Elisa might never have returned.

When Fraser returned to England, she wrote a salacious narrative that painted the Butchulla as savage, murderous cannibals. Her lies fueled a series of massacres against the Butchulla over the following decades. While the island has now returned to K’Gari, for over a century, it bore the name Fraser.

Butchulla people celebrating in 2023, when K’Gari’s name was officially restored. Photo: Darren England

Andrew Petrie, return or recapture

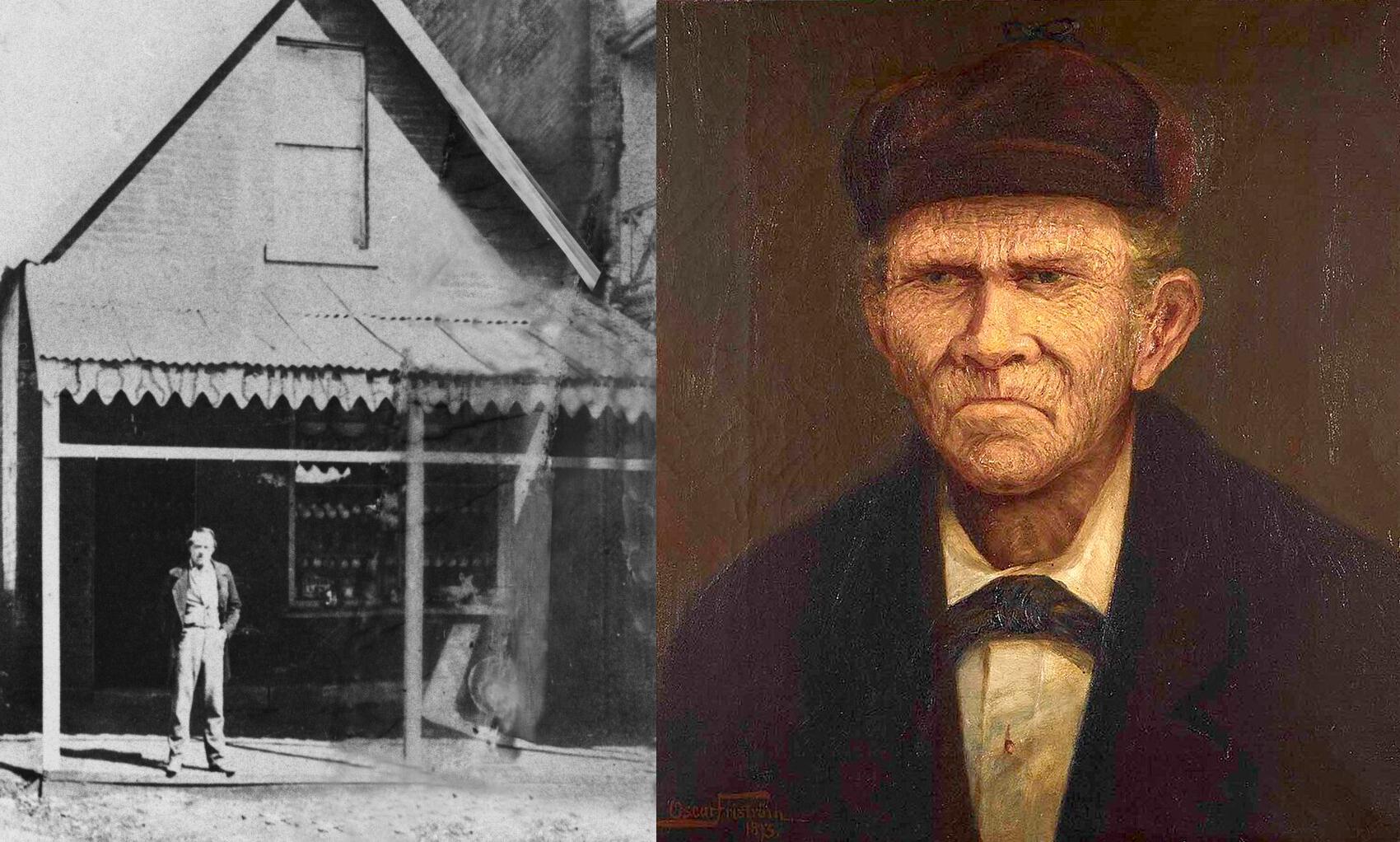

In 1824, 16-year-old Scotsman James Davis was convicted of stealing half a crown (12.5 cents) from a church and sentenced to transportation for life, which seems a bit extreme. In 1828, he was moved to Moreton Bay for a robbery conviction. Six weeks after arriving, he absconded with another prisoner.

The pair soon met the Ginginbarrah tribe, led by chief Pamby-Pamby, who adopted Davis as his deceased son, calling him Duramboi. The other convict was eventually killed for destroying a sacred burial site, but Davis remained. As Duramboi, he traveled widely, learning several Aboriginal languages, engaging in scarification and, allegedly, cannibalism.

In 1842, Andrew Petrie, a convict administrator and explorer, was journeying through the Wide Bay area. He was astonished to see a “wild” white man living with the Ginginbarrah. With Petrie was none other than Wandi, also known as David Bracewell. Petrie had run into Bracewell on the same journey and explained that the Moreton Bay settlement was decommissioned, and promised Bracewell would not be punished if he returned.

Bracewell and another man “stole in upon” the Ginginbarrah and dragged Davis out. Davis was furious, but Bracewell and Petrie eventually convinced him that he was free. Davis had to relearn English and get used to stifling, European-style clothes again. He worked as a guide and translator when called upon, but mostly he lived in Brisbane and sold crockery.

David Bracewell later claimed to have also been involved in the Stirling Castle affair. This may have just been big talk, though. At any rate, he was crushed to death by a falling tree in 1844.

James Davis/Duramboi in front of his crockery shop, left, and painted in his old age, right. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The names we don’t know

John Graham got his ticket of leave for the Stirling Castle affair, and promptly disappeared forever from the historical record. It’s possible that he returned to the community he’d been part of for six years.

Out of the 145 Moreton Bay prisoners who ran, 98 of them never returned and were never found. Most, certainly, died. But there must have been a lucky, clever, and perhaps personable few who lived out their days with the Aboriginal communities who found them. According to Andrew Petrie, “Had I or someone else not brought [James Davis] from among those savages, he would never have left them.”

George Mitchell said there were at least a dozen escaped convicts living in the territory, under the protection of Ngumundi and his kin. Most of them remain a mystery.