This week marks two years since the death and 95 years since the birth of Tom Hornbein, one of the great figures of American mountaineering. Best known for his 1963 first ascent of Everest’s West Ridge and the first traverse of the mountain with Willi Unsoeld, Hornbein left behind more than just a legendary climb.

He also made a lasting contribution to high-altitude climbing technology: the design of a revolutionary oxygen mask that changed the way climbers breathed on the world’s highest peaks.

The problem at altitude

In 1960, during the American–Pakistan Karakoram Expedition to Masherbrum (7,821m), Hornbein experienced the limitations of the oxygen systems of the day.

The Swiss-designed masks (designed for Everest in 1956) that Hornbein and co. used on Masherbrum were hard to breathe through. “When we got up high and put them on, we found ourselves ripping the mask off and gasping for air,” he later recalled.

Ice buildup in the valves, high breathing resistance, and complex designs made them unreliable and exhausting to use in the thin air above 7,000m.

Masherbrum from the Baltoro Glacier in northern Pakistan in 1953. Photo: lamountaineers.org

As a trained anesthesiologist and physiologist, Hornbein understood respiration as few climbers did. Where others cursed their equipment, he saw a solvable problem: to design a simpler, more efficient, and more reliable mask for oxygen systems.

The Maytag Mask

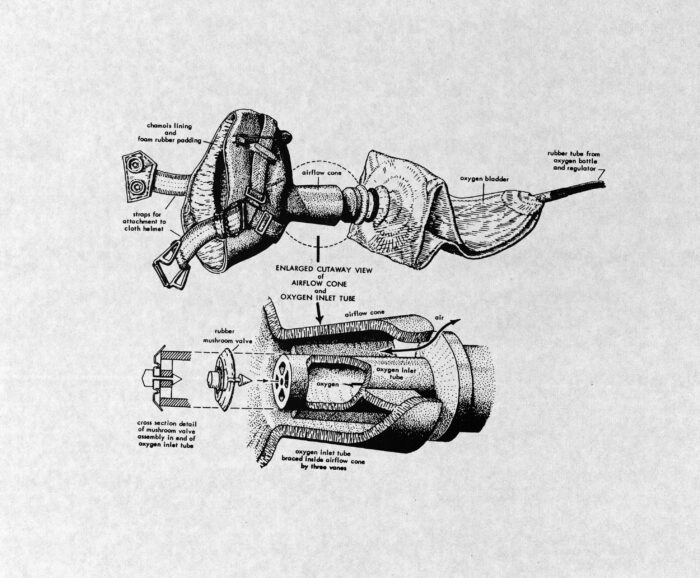

Hornbein’s early design called for a single-valve mask that reduced resistance to airflow and eliminated the tangle of inspiratory and expiratory valves prone to freezing.

The concept was elegant: one valve instead of multiple, and the whole unit molded as a single piece of flexible rubber. If ice did form, it could be crushed away with a mittened hand.

Maytag mask system used on the 1963 American Mount Everest expedition. Figure: University of California, San Diego, Mandeville Special Collections Library.

The challenge was manufacturing. By chance, Hornbein met Fred Maytag, of washing machine fame, who was recovering from surgery at Washington University Medical Center, where Hornbein worked.

Maytag’s company took on the project, crafting molds and prototypes in its research division. Though better known for producing household appliances, Maytag’s engineers built a mask that would soon help put six Americans on the summit of Everest.

Proven on Everest

Field tests on Mount Rainier in 1962 and in hypobaric and cold chambers demonstrated the new design’s advantages. The Maytag Mask, as it became known, showed dramatically lower resistance to breathing and could be de-iced easily.

When used on Everest in 1963, it performed perfectly. Climbers found it so natural to breathe through that very little training was required.

Hornbein on the West Ridge of Everest in 1963, wearing the Maytag mask. Photo: Tom Hornbein

The simplicity of the design also meant reliability. Where previous models froze solid or clogged with moisture, the Maytag mask kept working in the extreme cold and high winds. It was, Hornbein wrote, “a solution to the problems of high mask resistance and ice accumulation.”

Foundation of modern systems

The Maytag mask became the template for most high-altitude oxygen systems that followed. Later designs incorporated multiple valves and lighter materials, but the underlying principles of low breathing resistance, a one-way valve to prevent rebreathing, and a flexible body that could be squeezed to clear ice all trace back to Hornbein’s prototype.

A modern oxygen mask on Everest. Topout Oxygen Ltd/Facebook

Hornbein’s work bridged the gap between wartime aviation oxygen systems, which influenced early mountaineering masks, and the specialized mountaineering equipment used by climbers today.

Modern models, such as those made by TopOut or Poisk, still bear a clear lineage to the Maytag mask, refined through better materials and flow regulators but unchanged in their fundamental design.

A lasting legacy

After Everest, Hornbein went on to a distinguished career at the University of Washington, becoming a well-known professor conducting research on respiratory physiology and anaesthesiology. Yet, even decades later, he remained modest about his mountaineering fame. He didn’t want to be known as the doctor who climbed Everest. But his influence in both physiology and the high mountains endures.

Tom Hornbein. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Two years after his passing, it is fitting to remember not just the man who stood on Everest’s West Ridge, but the one who helped countless others breathe a little easier on their own climbs toward the roof of the world.