Jordi Corominas of Spain has received the Walter Bonatti Lifetime Achievement Award from the Piolet d’Or committee.

Well known among fellow climbers, Corominas’s name might be unfamiliar to many readers — not because his achievements are not worth it, but because he has avoided the spotlight throughout his climbing career.

A man of few words and a full-time UIAGM mountain guide, he is not what contemporary audiences picture as a celebrated climber. He doesn’t pose with Guinness record certificates, doesn’t have a press team, and doesn’t take selfies at mountain festivals. The guy doesn’t even do Instagram! Believe it or not, he still prefers books.

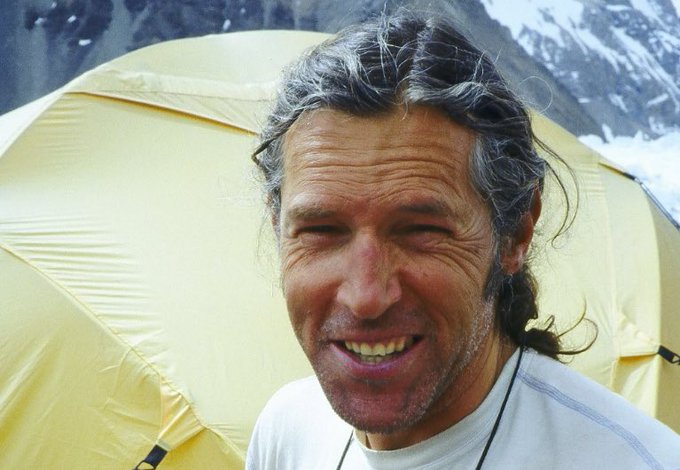

Photo: Jordi Corominas

Born in 1958 in Barcelona, he is a long-time resident of Benasque, a small mountain town in the Spanish Pyrenees. He has always placed style above records and chooses his goals not by their popularity but by their difficulty and aesthetics.

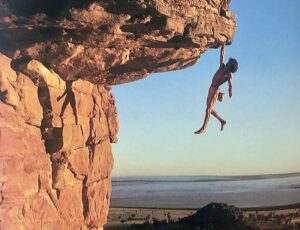

He started young. Corominas was just two weeks old when his mom took him on his first bivouac in the mountains. In the 1990s, he did all the hard, long routes in the Pyrenees, summer and winter. Along the way, he opened a series of new rock and mixed lines. At the turn of the millennium, he moved on to the higher ranges: the Andes, Patagonia, and the Himalaya.

High-altitude climbs

These included Indian peaks such as Thalay Sagar, Shivling, and Meru; Andean nevados and Patagonian spires; and some unfulfilled dreams, such as the new route he attempted on Tengi Ragi Tau in 2008.

On the 8,000’ers, Corominas started off with Dhaulagiri in 1991, made a no-oxygen attempt on the North Side of Everest in 2000, and Gasherbrum II in a single push in 2006. Other than these, he never showed great interest in the standard routes. The Himalayan giants offer other faces to the most daring. In Corominas’s case, two peaks marked his career: K2 and Lhotse Shar.

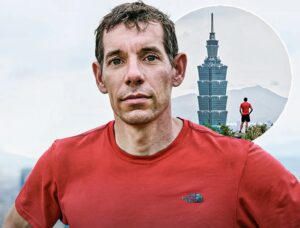

Corominas on Lhotse Shar. Photo: Barrabes.com

Lhotse Shar was the first peak he tried in the Himalaya, a crazy attempt at a very young age in 1988. He attempted the Austrian route and reached 7,400m. He returned quietly in 2010, also trying the mighty South Face of Lhotse Main. In 2019, he made a third attempt on Lhotse Shar, as well as the South Face of Nuptse.

It is characteristic of Coromina — and one of the reasons he is not so well-known — to aim high and not be afraid to fail. This happened on Lhotse Shar, on Gasherbrum IV (two alpine-style attempts in 2006), and on the South Face of Shisha Pangma in winter.

The pirates of K2

Yet Corominas’s career will always be linked to the Magic Line on K2. At the time, the Magic Line — up the SSW Ridge of K2 — was considered to be the hardest technical ascent of the mountain. Climbed only once and never attempted since then, it was a “suicidal line,” in the words of Reinhold Messner.

Corominas achieved the second ascent ever on a solitary push after his climbing partners retreated. No one has done it since.

Apart from its success, the expedition was distinguished by its creative, ambitious approach, its Jolly Roger flag at Base Camp, and the Bonatti Forever sign at the mess tent. It was also a turning point in how expeditions communicated with audiences: open, honest reporting on their progress, accompanied by stunning pictures at a time when there was the internet but no social media or smartphones.

ExplorersWeb was there to share the news, and the community behind us lived the team’s difficulties and waited tensely as Corominas continued alone up the mountain. We also cried with the team as Manel de la Matta suddenly fell sick in Camp 1 and died.

The K2 Magic Line team at Base Camp in 2004. Left to right, Oscar Cadiach, Valenti Giro, Manel de la Matta, Jordi Tosas, and Jordi Corominas. Photo: K2 Magic Line Expedition

For such a communicative expedition, it was quite peculiar that Corominas, the only summiter, was the least keen to speak about it. His refusal to give interviews or speak too much about the climb only enlarged his fame. He just kept guiding, planning his own climbs, and listening rather than speaking.

A transitional figure

Corominas represents a transition from the wild and somewhat reckless 1980s to a more carefully planned, technical approach to high-difficulty routes on higher mountains. But most of all, he defines himself as a transmitter of the knowledge he has received from his parents, his teachers, and his friends.

Hence, he has devoted his life to guiding and teaching others as a professional guide (still active) and as a coach of younger alpinists.

Corominas ice climbs at home in Benasque. Photo: Verticualidad

At the beginning of December, he will have to book a couple of days in his calendar and travel to San Martino di Castrozza in the Italian Dolomites, to take the stage and receive his golden ice axe, not for K2 or any other route, but for a lifetime of them.