Stretching for around 2,000km from Washington State to Alaska, the Inside Passage is one of North America’s great expedition kayaking routes. It winds through channels, fiords, and islands along the Pacific coast of British Columbia and Southeast Alaska.

It offers paddlers a rare combination of long-distance expedition potential, rich scenery and wildlife, and maritime challenges that test skill, planning, and patience.

The route

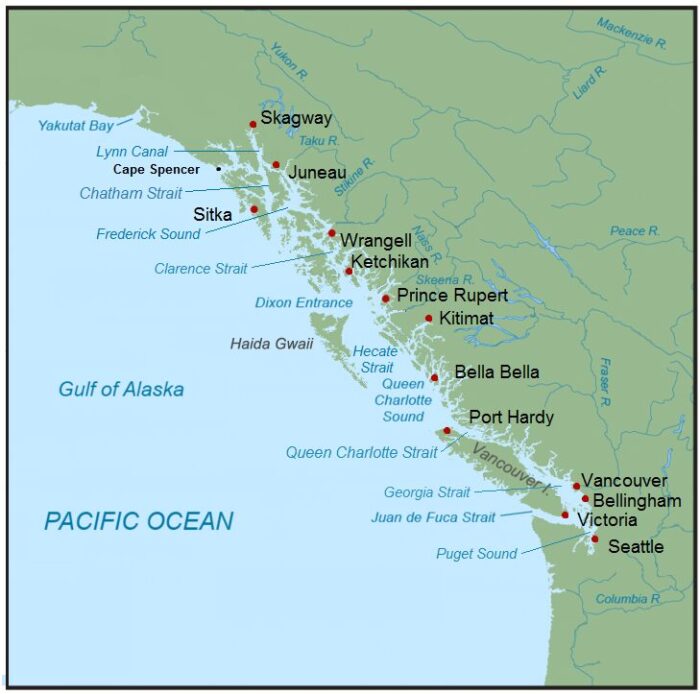

There is no single route. The Inside Passage is essentially a corridor of interconnected waterways, protected in many places by islands, but punctuated by open crossings fully exposed to Pacific swell. A typical kayak journey covers 1,200 to 2,000km, depending on start and finish points.

Many paddlers begin near Anacortes or Bellingham, Washington, and end in Prince Rupert, British Columbia. Some continue further north through the fiords to Ketchikan, Juneau, or Skagway, Alaska.

The Inside Passage. Image: Wikipedia

Earlier this year, 35-year-old Canadian Pascal Smyth paddled 2,202km from Vancouver to Skagway over 72 days. Smyth chose the “sheltered” version of the route, avoiding paddling along the outer coast and around Vancouver Island or around Haida Gwaii, which you could argue would make it more of an “Outside Passage”.

“While paddling along the outer coast would have been gorgeous in some spots, I wanted to stay fairly true to the idea of the Inside Passage,” explained Smyth.

“The west coast of Vancouver Island would have been an awesome challenge, but with the significant exposure to swell coming from the Pacific, it has the potential to cause significant delays due to poor weather,” he added.

Inside Passage scenery Photo: Pascal Smyth

The Inside Passage passes through various remote coastal communities, offering the chance for resupply. These include Port Hardy on northern Vancouver Island, Prince Rupert, Ketchikan, Wrangell, and Petersburg. Between them lie hundreds of kilometers of wilderness and channels lined with temperate rainforest, steep granite walls, and wildlife-rich estuaries.

Open crossings

The route is not all sheltered, though. Several open-water stretches test even experienced kayakers.

Cape Caution, at the northern tip of Vancouver Island, is one of the best-known obstacles. On this exposed 20km section, the route leaves the protection of the islands and can face serious swell, wind, and breaking surf. There are no real landing options.

“Cape Caution presented a significant obstacle. I knew this would be one of the sections most significantly affected by adverse weather, so I planned accordingly,” Smyth recalls.

Coast Mountains across Queen Charlotte Strait. Photo: alexsidles.com

Smyth had resupplied at Port Hardy and holed up nearby when wind and rain hit. Then he raced across Queen Charlotte Strait, which separates Vancouver Island from the mainland at the picturesque Burnett Bay.

“I was fortunate to have outrun the incoming weather system, which brought gale-force winds and huge swell. I spent a few days on land there as well, exploring the beach and feeling relieved to not be out on the water in those conditions,” said Smyth.

Burnett Bay, one of many sandy beaches along the Inside Passage. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Cape Caution

“After a few days, the wind and swell died down, and I rounded Cape Caution. I believe the swell was forecast at 1-2 meters when I paddled past. It was largely a non-issue.

“I knew I could be substantially delayed on that leg, but with the supplies I picked up in Port Hardy, and knowing I had another box of supplies awaiting me in Shearwater, I could afford to wait out the weather,” Smyth said of his tactics.

North of the port city of Prince Rupert, the Dixon Entrance crossing into Alaska is another serious undertaking, with a long fetch, ocean swells, and limited landing options. Smyth chose to stick to the shoreline here and make a short crossing between islands close to the mainland.

“It was a benign crossing, with hardly a ripple on the water,” said Smyth. “That fair weather continued for much of my travels in Alaska. I was very fortunate.”

An idyllic cove south of Bella Bella. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Tides and currents

The entire route is governed by tides that can exceed four meters and generate powerful currents in narrow channels, sometimes up to 10 knots.

“Ideally, I would get to camp exactly at the highest tide and depart on another high tide so that I could minimize the effort of hauling gear up and down beaches,” Smyth said.

Photo: Pascal Smyth

“It seldom worked out perfectly. Some beaches are very difficult to land on if not at a perfect tide height, with reefs of boulders presenting a real obstacle to a relatively fragile composite kayak,” he added.

Glacier Bay, Alaska. Photo: Shutterstock

“Some areas with significant currents were the Yaculta Rapids, Gillard Pass, and Dent Rapids, which are close enough together that I was able to effectively treat them as one long section of current, as well as all the channels flowing into, and including Johnstone Strait itself.”

The currents at the mouth of Glacier Bay also presented a significant challenge for Smyth, though he did get a chance to see humpback whales feeding right next to him. “They must have been using the current to funnel fish into their mouths,” the kayaker recalled.

Surf and landings

Landings along the Inside Passage can vary from calm sandy beaches to steep rock shelves and surf-pounded headlands. Technical surf landings may be required in certain areas, particularly near open crossings. Choosing appropriate tide states for landing and launching can make the difference between a controlled entry or exit and a real epic.

Landing through surf. Photo: SeaKayaker.org

“I was able to avoid surf landings for the most part, generally choosing beaches without too much exposure. Burnett Bay is a notable exception,” said Smyth.

Following storms, driftwood can present a serious hazard, either making it hard to land on some beaches or littering potential campsites with broken wood.

“The toughest campsite was one on the North end of Princess Royal Island,” Smyth said. “The large rocks and huge drift logs presented a real challenge, and the steep forest behind had no attractive options. I ended up rigging my hammock above the driftwood, though the slippery logs made that task rather treacherous.”

An uncomfortable camp. Photo: Pascal Smyth

Wildlife encounters

The likelihood of wildlife encounters in the Inside Passage is a major draw for many paddlers. Humpbacks and orcas frequent the channels, as well as sea lions and porpoises. Along the shorelines, black bears and grizzlies forage at low tide, while bald eagles are a common presence.

“I had an unforgettable encounter with a large pod of orcas before I got to Shearwater and innumerable encounters with humpback whales, particularly as I explored Alaska. In Glacier Bay they would regularly feed right next to shore,” Smyth recalled.

Whale encounters are common. Above: Pascal Smyth. Below: Jerry Kobalenko

“I had a few instances where they would swim underneath while feeding, and I would do my best to give them space. Ultimately, they go where they want and don’t seem especially bothered by a little kayak. Though they don’t mean any harm, it was still pretty alarming to see a tail rise from the water right beside my kayak,” he added.

Photo: Pascal Smyth

Smyth also saw many bears, including seven grizzlies, in the hour before setting up camp.

“That was on Admiralty Island, where the grizzly population is about 1 bear per square mile,” he said. “On that night, as well as a few others, I set up a portable electric fence to give me some extra peace of mind.”

Thankfully, the bears showed little curiosity around him. “The bears were quite disinterested in me. I never had any evidence of animals checking out my gear the entire trip.”

Unforgettable journey

Whether paddled in sections or as a full traverse, the Inside Passage demands respect for tides, weather, and distance, and the patience to wait for safe conditions.

As Pascal Smyth reflected after completing his 2,200km paddle, “Though this was a long trip, not a single day felt impossible. I took it day by day and kept at it, doing my best to savor the highs and lows of what proved to be an unforgettable journey.”