When you Google L’Oiseau Blanc (The White Bird), the first thing that comes up is a two-star Michelin restaurant with views of the Eiffel Tower. But L’Oiseau Blanc was also a plane, and part of a legendary aviation mystery. In 1927, a Levasseur PL.8 biplane was modified to carry two aviators on a daring non-stop transatlantic flight from Paris to New York. The men took off into the cloudy skies, prepared to tackle whatever came their way. However, they never reached their destination, disappearing somewhere over the Atlantic.

A highly coveted prize

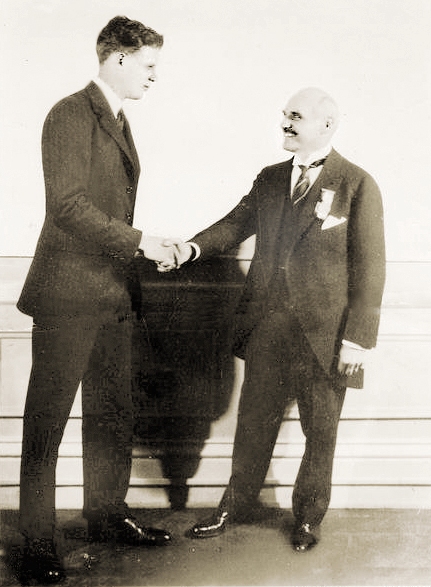

From the early to mid-1900s, Raymond Orteig climbed the ranks of the hotel industry in New York. His ambition and work ethic transformed him from a waiter to a hotel owner. But he was also enthralled by the tales of aviators who stayed at his hotel and the technological advancements driven by the Great War.

Raymond Orteig, right, shakes hands with Charles Lindbergh. Photo: Alan R. Hawley

In 1919, British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown completed the world’s first transatlantic flight. Their journey, from St John’s, Newfoundland, to Ireland, heralded a new age for travel. Their flight took under 72 hours, and the achievement won them a £10,000 prize. The news spurred Orteig to push aviation a step further, to try a non-stop transatlantic flight from Paris to New York.

Orteig took his idea to the Aero Club of America for approval, offering a monetary reward of $25,000 to the aviators who could make it happen. It was a daunting challenge. A journey from Paris to New York would cover 5,793km, and weather conditions over the Atlantic were highly unpredictable.

An unlikely team

During World War I, pilot Charles Nungesser made a name for himself. He claimed 21 aerial victories, held 30 citations, showed extreme bravery (often borderline recklessness), despised authority, and had a reputation as a Lothario. He often got into trouble and was placed under house arrest several times.

Nungesser caught the eye of Francois Coli. Coli was an aviator with an impressive track record in the French Air Service. He was described as a good leader, steady, level-headed, and an excellent navigator.

When the war ended, Coli did not want to give up flying. Sensing that the world was on the cusp of an aviation revolution, Coli began to experiment with long-distance flights. In January 1919, he achieved the first double crossing of the Mediterranean with his colleague, Henri Roget. He achieved another record by flying from Paris to Morocco a few months later.

Coli heard about the Orteig prize, and he decided it could be done. He intended to fly from Paris to New York with his friend Paul Tarascon. However, Tarascon was badly burnt in an accident, forcing him to withdraw from the project.

Francois Coli and Charles Nungesser. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum

Coli needed another partner and approached Nungesser, who couldn’t refuse the chance of glory. Strangely, their very different personalities did not hinder their ability to work together. They balanced each other well, respected each other’s skills, and trusted each other.

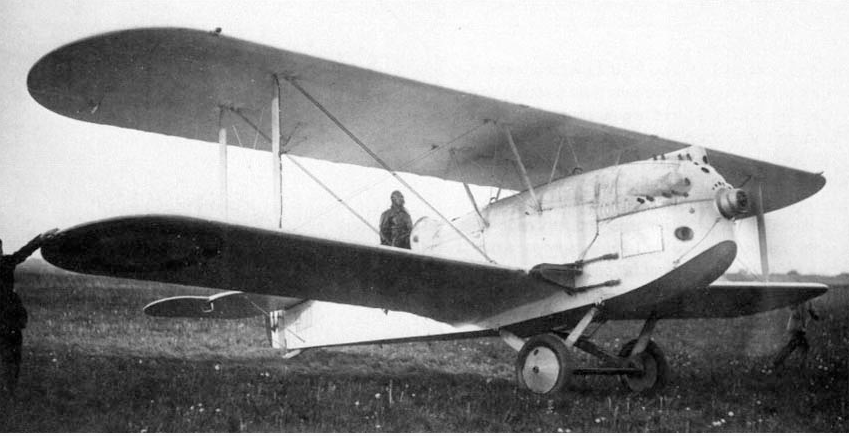

The White Bird

They chose a Levasseur PL.8 biplane. It had an open cockpit where the pilots could sit side by side, floats attached to the undercarriage so they could land at sea, fixed landing gear, and it contained two big fuel tanks to hold over 4,000 liters of gas. The plane measured 9.75m in length, had a 15m wingspan, and weighed 5,000kg. It was capable of reaching just under 200km per hour, 7,000m altitude, and could fly for 40 hours nonstop.

The frame was made of wood, and the cover was linen canvas. Painted white, the pair added personal touches: Nungesser added his army insignia of a skull and crossbones, coffin, and candles, and Coli painted the French flag.

To reduce weight, the plane had no radio, an extremely risky move.

An ill-fated journey

On May 8, 1927, Nungesser and Coli were greeted by a large crowd at the Le Bourget Airfield outside Paris. They planned to fly across the English Channel, over southwest England, up to Ireland, across the Atlantic to Newfoundland, and then continue south to New York. They hoped to land in the water next to the Statue of Liberty.

At roughly 5 am, they departed, barely getting the plane airborne due to its weight. They received an escort from the French Air Force, who last saw them flying over Étretat. Later, the British Navy saw them flying over southern England. There was a possible sighting in Ireland, but then reports stopped.

Coli and Nungesser did not arrive in New York 40 hours later, and hours turned into days with no news.

A frantic search began, bringing together naval forces from around the world. French, American, and Canadian forces scoured areas along the predetermined route but found nothing. The effort included aerial and ground searches in Newfoundland, Labrador, New England, and New York. The search was overshadowed by the bittersweet news of Charles Lindbergh’s successful New York to Paris transatlantic flight, earning him the Orteig prize.

The White Bird. Photo: Marcel Jullian

Theories

Locals reported spotting a white biplane in Newfoundland on May 9. Twelve residents of Harbour Grace spotted a plane flying in a sea of fog. Witnesses heard a plane sputtering over Harbour Grace and St Mary’s, and some claimed to see it trailing smoke. One woman remembered hearing three explosions, while someone else found a strange metal object stuck in a pond, believing it was a piece of the plane.

In the 1980s, American author Gunnar Hansen investigated what happened to the men. His research led him to Maine, where local legends told of a plane crash deep in the woods near Round Lake. He became acquainted with a man named Anson Berry, who claimed to have heard the plane crash.

In his article for The Yankee, Hansen recalls Berry’s description:

The engine sounded erratic. Moments later, it stopped, and Berry heard what he described years later as a faint, ripping crash. The afternoon was wearing on, and the always unsteady spring weather was worsening; already rain was beginning to fall. Perhaps because he did not trust the weather to hold, Berry did not investigate what he heard.

Hansen also described the weather conditions through which the men would have had to fly:

The next day, rain squalls covered Newfoundland, and light snow was falling at Cape Race. Fog shrouded the northeastern U.S coast, and those who waited in New York wondered how the Frenchman would be able to find the harbour, even if they did reach it.

William Nungesser, a relative of Charles, also searched Maine but found nothing. In the 1990s, the National Underwater Marine Agency (NUMA) launched Project Midnight Ghost, with divers searching for a plane at the bottom of the Great Gull Pond in Newfoundland. However, like W. Nungesser and Hansen, they left empty-handed.

The consensus is that Coli and Nungesser met their end somewhere on the continent. As to what happened before the crash, perhaps wind and fog conditions reduced the pair’s visibility. Historians agree that the weight of the plane would have made it difficult to control.

Lost but not forgotten

Some people still hope to find L’Oiseau Blanc. The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), founded by Richard Gillespie, keeps an eye out for any information that could help the search. Gillespie searched St Mary’s in Newfoundland and believes that “the pilots might have tried to put the plane down somewhere, hit a hidden boulder beneath the surface, and crashed.”