In the autumn of 1988, a team of Slovak climbers set out to tackle Everest’s Southwest Face, a steep and unforgiving route first climbed by Chris Bonington’s British team in 1975. That earlier climb used siege tactics, with fixed ropes, camps, and bottled oxygen.

The Slovaks wanted to do it differently, in alpine style, carrying everything themselves, no oxygen, no Sherpas, no pre-set camps. It was a bold plan, one of the toughest climbs ever attempted on Everest. They succeeded, but at a terrible cost: One man reached the summit, but he and three others disappeared on the descent.

The team

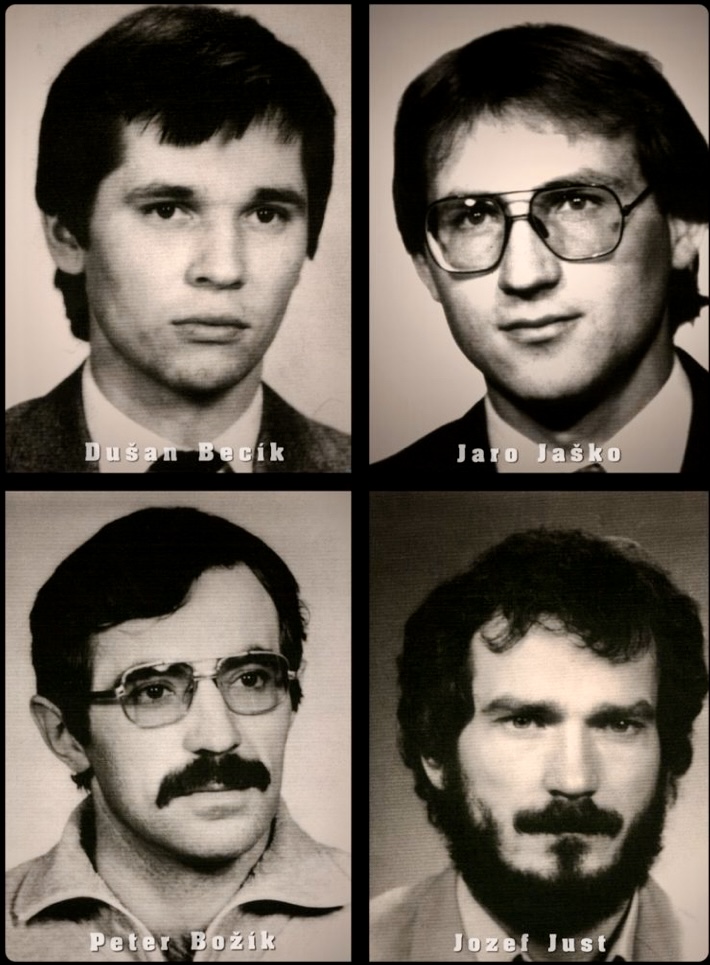

The Slovak team was led by Ivan Fiala, a 47-year-old mountaineer from Bratislava with years of experience in the Himalaya. For this expedition, he remained at Base Camp, overseeing the operation. His deputy, Jaroslav Orsula, handled logistics, while Dr. Milan Skladany kept an eye on the team’s health. The climbers chosen for the Southwest Face were four strong alpinists from Slovakia’s Tatra Mountains: Dusan Becik, 34, a technician; Peter Bozik, 34, a blacksmith; Jaroslav Jasko, 27, an engineer; and Jozef Just, 33, a calm and steady climber. All were skilled, tested on tough peaks, and ready for Everest’s challenge.

The goal

The team planned to repeat the 1975 British route up the Southwest Face, but without the heavy support. They would carry minimal gear and move fast, climbing as a tight group. First, they would acclimatize on Lhotse, using its West Face to prepare their bodies for high altitude. Then they would switch to Everest, aiming to climb the Southwest Face in two or three days, and descend via the South Col and Southeast Ridge.

It was a daring idea, especially without oxygen, which even Bonington had called impossible for this route. The route, known as the Hard Way, featured steep ice couloirs, a notorious rock band with chimneys rated V-VI on the UIAA scale, long snow traverses prone to avalanches, and exposure that left little room for error.

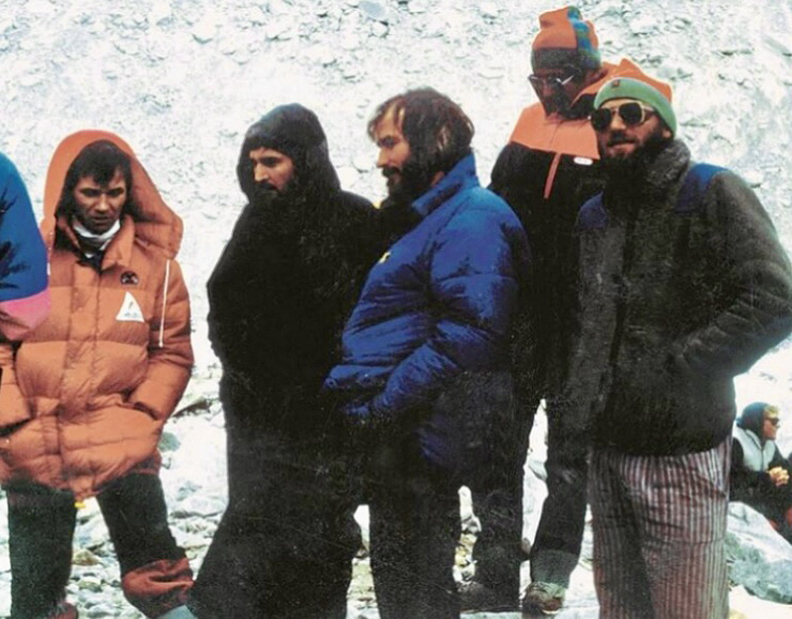

Everest Base Camp, 1988. Dusan Becik, Milan Skaldany, Josef Just, Peter Bozik, and Jaroslav Jasko. Photo: Goat.cz

Deals at Base Camp

The expedition was officially a joint “Czechoslovakia-New Zealand” effort, but the two groups operated mostly on their own. The New Zealanders, led by Rob Hall, had their own plans for Everest’s South Pillar and Lhotse’s West Face, but they shared the permit and some Base Camp resources. This partnership helped with negotiations in the crowded Base Camp, where Fiala’s party arrived on Sept. 9, 1988. To reach the Western Cwm, the flat valley below the Southwest Face, the Slovaks had to cross the Khumbu Icefall.

By that time, U.S. and French expeditions had already set up ropes through the Icefall, charging $7,000 for their use. It was a huge sum for the Slovaks, who came from a communist country with little money. After negotiations, the French permitted Fiala’s team to use the ropes. The Americans also agreed, in exchange for gear and food. The South Koreans also consented after the Slovaks promised to fix ropes to Camp 4 on Lhotse, which the Slovaks planned to climb as part of their acclimatization. These deals were crucial; without them, the expedition might have stalled before it began.

Jasko, Lydia Bradey (NZ), Just, and Becik in Everest Base Camp, 1988. Photo: Goat.cz

Establishing camps

In the first weeks, Becik, Just, and Jasko worked hard to set up camps. They placed Camp 1 at the top of the Khumbu Icefall, Camp 2 in the Western Cwm at 6,400m, and Camp 3 at 7,250m on the steep, icy Lhotse Face. Sherpas helped with food and materials to Camp 2, but the upper work was a team effort.

Fiala stayed at Base Camp, talking to the climbers on the radio. Orsula kept supplies organized, and Skladany checked for signs of altitude sickness: headaches, nausea, or worse. The doctor noted how the thin air stole appetites and sleep. Base Camp life was a routine of boiling snow for tea, repairing gear under prayer flags, and watching storms roll in from the east.

Becik on Lhotse. Photo: Goat.cz

Acclimatizing on Lhotse

Before their main goal on Everest, the team needed to acclimatize. On September 21, after a spell of bad weather, they started up Lhotse from Base Camp. Becik and Just led the way from Camp 3. After seven hours, they reached 8,050m and bivouacked for four hours in a small tent.

That night, September 27, they climbed by moonlight. On September 28 at 6:00 am, Becik and Just reached Lhotse’s 8,516m summit without bottled oxygen. The ascent was a seven-hour grind from Camp 3, pushing through fixed lines the team had helped place for the Koreans. At the top, the views stretched to the horizon: Everest’s black pyramid dominating, the curve of the Kangshung Glacier below.

Bozik and Jasko went as far as Camp 4 at 7,900m, spending a night there before turning back. They bivouacked just under the chimney leading to the summit, enduring a couple of hours in the open before descending, saving their energy for Everest.

All four descended to Camp 2 on September 28 and Base Camp on September 29. Lhotse had done its job: Their bodies were ready. Fiala praised it as a key step, noting how the four strong climbers — now battle-tested — emerged hungrier for the face. Radio reports from the descent spoke of fatigue but no major issues, and Skladany’s checks at Base Camp confirmed improved altitude tolerance.

Everest’s ‘Hard Way,’ marked in yellow. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

The first try on Everest

On October 7, Becik, Bozik, Jasko, and Just started their first attempt on Everest’s Southwest Face.

They moved through the Icefall and reached Camp 2 in the Western Cwm, but strong winds hit hard, trapping them in their tents. The next day, the weather was too bad to climb higher, and they retreated to Base Camp. It was a setback, but they weren’t done. They rested, ate, and waited for a better chance. Skladany checked them over, noting fast heartbeats and tired eyes, but they were still strong. Orsula made sure their gear was ready: one tent’s inner lining, two sleeping bags (for Bozik and Jasko, who planned to try Lhotse later), three days of food, a stove with gas, 240m of rope, four ice axes, two ice hammers, three small cameras, and one light video camera. No oxygen.

This first probe exposed the Face’s temperament. Winds howled down the couloirs, whipping spindrift into blinding sheets, and the lower ramps felt steeper than photos suggested. Back at Base Camp, Fiala reviewed the reports, adjusting expectations. The delay built tension, but it also allowed recovery.

The upper section of Everest’s Southwest Face. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

Another push

On October 12, they tried again. They left Base Camp, crossed the Icefall, and reached Camp 2. Winds kept them there on October 13, but at 3 am on October 14, they started up. The first day was tough. They had planned to climb a key couloir, but the ice was harder than expected, and technical sections slowed them down. By 7 pm, they stopped at 8,100m, setting up their first bivouac on a platform they carved out of the snow.

The lower wall proved a rude welcome. Icy terrain demanded constant axe work, and a difficult stone wall rated V-VI UIAA loomed, forcing careful route-finding. Just radioed down that progress was slow, but the group felt solid, with no health complaints yet. Digging the platform took precious energy; the cold night tested their minimal sleeping setup.

October 15 was clearer, but the Rock Band’s chimney — a steep, narrow section from the 1975 route — was harder than they thought. It took all day to climb, with icy holds and loose rock. By 5 pm, they reached 8,400m, above the Rock Band, and made another bivouac. They were moving more slowly than planned, but the summit was close. No one reported any issues, and the radio crackled with steady updates, Fiala noting the climber’s resilience.

Everest’s Southwest Face. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

A third bivouac, concerns start

On October 16, they faced a long snowfield, sloping to the right. It was slow going, with soft snow and hidden hard patches. Becik started to struggle, feeling sick, weak, and vomiting in the morning. His strength sapped, the others were forced to match his faltering rhythm. The group stayed together, but it took the whole day to cross.

At 7 pm, after two and a half hours of digging, they set up their third bivouac at 8,600m, just below the South Summit. Fiala, at Base Camp, was worried. The team was behind schedule, and Becik’s condition was a red flag. Over the radio that night, the team said Becik was better.

The platform at 8,600m was tiny, the wind probing for weaknesses in their tent liner.

Pushing alone for the summit

On October 17, at 9 am, they started for the South Summit, hoping to reach it by 10 am, and the main summit by 11. The route was steep but familiar from other climbs. By 10 am, they made it, but the team was breaking apart. Becik, too weak to go on, stayed below the South Summit. Bozik and Jasko (whose vision was blurry, likely from retinal hemorrhages caused by altitude) headed toward the South Col, planning to save energy for Lhotse later. Just went on alone.

The four Slovak climbers from the summit bid. Just summited alone. During descent, all four climbers perished. Photo: Dmff.eu

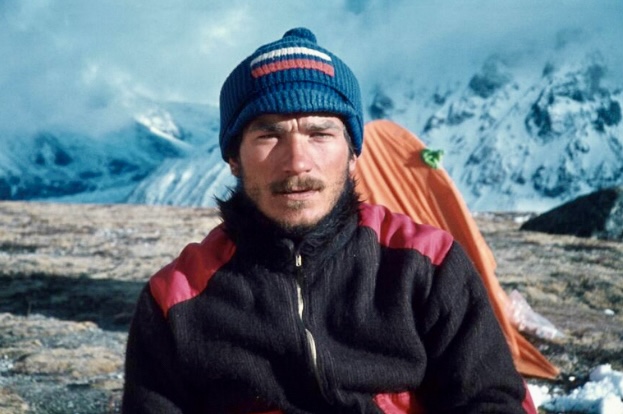

On October 17 at 1:40 pm, Just radioed Fiala: He was on Everest’s summit, alone, after completing the first alpine-style, oxygen-free ascent of the Southwest Face. He described bitter cold and strong winds, staying only 15 to 20 minutes on top to take photos. Unsure of Bozik’s and Jasko’s positions, he scanned the ridge, seeing only clouds. By 2 pm, he started down. At 3 pm, from the South Summit, he found Becik had moved from where he’d waited. Bozik and Jasko were out of sight, probably heading to the col. Just’s vision was failing too, with spots clouding his eyes.

A call that never came

At 4 pm, Just radioed that he had met Becik and Jasko. Jasko was sluggish, barely moving, and needed urging to descend. Bozik also had vision problems and felt lost. At 5 pm, Becik caught up from above, his eyesight clearer, and took the lead. By 5:30 pm, at 8,300m, halfway to the South Col, they said they could see the route and were okay. They promised another call in two hours from the col. It never came.

At 6 pm, three Americans reached the South Col. The sky was clear, and they could see the route to the South Summit. No one was there, no climbers, no headlamps. By 11 pm, a fierce storm hit, with winds up to 160kph. At Camp 2, four of seven tents were ripped apart, likely blown down the east face. Fiala tried to organize a rescue, offering Sherpas 25 times their pay to check the col. However, the storm was too dangerous, and no one went.

Jozef Just. Photo: Goat.cz

The search

On October 18, at 10 am, the Americans checked again: South Col tents deserted, no signs up high, and Camp 3 empty below. They then descended.

Searches followed, but helicopters couldn’t fly, and climbers found nothing. Becik, Bozik, Jasko, and Just were gone, likely swept off by the storm or lost in crevasses on the Kangshung Face. Their bodies were never found.

Fiala, heartbroken, stopped climbing for good. Orsula and Skladany put up a plaque in Gorak Shep with the climbers’ names.

Legacy

The Slovak climb was a milestone. Reinhold Messner called it one of the greatest Himalayan efforts. Chris Bonington was amazed they did it without oxygen. No one has climbed the Southwest Face in alpine-style since. A 2020 film, Everest: The Hard Way by Pavol Barabas, tells their story, with Fiala’s voice carrying the weight of loss and pride. In Slovakia, climbers still talk about the four, their names a reminder of what’s possible, and what the mountains can take.

The tragedy underscored the limits of oxygenless assaults, yet Just’s summit — one man against the Hard Way — stands unchallenged in alpine purity.

A memorial for the four climbers who disappeared on Everest in 1988. Photo: SHS James