In the spring of 1982, a small British team set out to tackle one of the most formidable challenges in Himalayan climbing: the unclimbed East-Northeast Ridge of Everest from Tibet. During the attempt, Pete Boardman and Joe Tasker vanished in the Death Zone. We revisit their story.

By 1982, 117 climbers had summited Everest, but just six without supplemental oxygen. From its first ascent in 1953 until the end of 1981, 54 climbers died on Everest, and 41 of those didn’t use bottled oxygen.

Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay first confirmed ascent of the mountain in 1953 went via the Southeast Ridge (now the standard route from Nepal) under John Hunt’s leadership.

From the north, a Chinese team claimed a summit in 1960 via the North Col and North Ridge, though evidence is limited and the ascent is not universally accepted. In 1975, a Chinese team, including Phantog, the first woman to summit from Tibet, reached the top.

Other significant routes included the Southwest Face, climbed in 1975 by a British team led by Chris Bonington (Pete Boardman, Doug Scott, Dougal Haston, and Pertemba Sherpa topped out), and the West Ridge, summited by Americans Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld in 1963. A Yugoslavian team later completed a variation of the West Ridge route from Nepal in 1979.

Joe Tasker and Pete Boardman in 1982. Photo: Chris Bonington

The 1982 team

Led by Chris Bonington, the 1982 Everest team included Pete Boardman, Joe Tasker, and Dick Renshaw, all experienced mountaineers. Charles Clarke, the expedition doctor, and Adrian Gordon supported the team. Clarke and Gordon didn’t plan to climb above Advanced Base Camp. The climbers aimed to ascend without oxygen, using minimal equipment and snow caves for camps.

Before the expedition, Bonington, Boardman, Tasker, and Renshaw had already built remarkable climbing legacies.

Bonington was already a mountaineering icon. He had organized the 1975 Everest Southwest Face expedition, on which his team achieved a historic summit. He also led the first ascent of 7,719m Kongur Tagh in China in 1981, where Boardman, Tasker, and Alan Rouse summited in alpine style.

Boardman began climbing in the Peak District as a teenager before exploring the Afghan Hindu Kush in 1972 and the Pennine Alps in 1968. His fame grew with his 1975 Everest summit alongside Pertemba Sherpa. In 1976, Boardman and Tasker made history with their ascent of 6,864m Changabang’s West Face in India. They famously trained for the climb in a refrigerated meat factory to simulate harsh conditions. Their feat redefined lightweight Himalayan mountaineering.

The intense Tasker started his career with bold climbs like the Eiger’s North Face (in winter 1975 with Dick Renshaw). His partnership with Boardman took him to Changabang and the first British ascent of Kangchenjunga in 1979 (without supplemental oxygen).

Renshaw had also climbed Dunagiri in 1975 with Tasker.

The summit photo on Kongur Tagh, first ascent, 1981. Photo: Chris Bonington Picture Library

The team’s history of notable climbs prepared them for Everest’s unclimbed East-Northeast Ridge.

A tough route

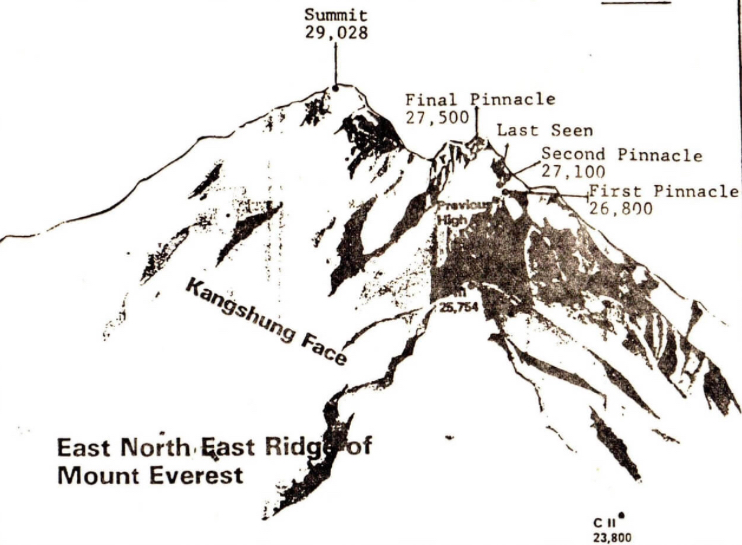

In mountaineering literature, their 1982 route is often referred to as the “full Northeast Ridge” route that includes three difficult pinnacles. This long, difficult line has its toughest challenges near the end, between 7,925m and 8,382m, where the ridge joins the North Ridge (the route taken by the pre-war expeditions and the successful Chinese expeditions of I960 and 1975).

Their route differed from the standard northern climbing route that joins the Northeast Ridge at the North Col (at 7,000m), avoiding the pinnacles and following a less technical line to the summit.

Everest East-Northeast Ridge. Photo: Chris Bonington

Arrival at Base Camp

Bonington’s team reached Base Camp at 5,180m on March 16, after a three-day drive from Lhasa. Ten trekkers joined them, exploring the Rongbuk Glacier and reaching 6,100m.

Bonington’s team placed Base Camp near the glacier, just above the sites of the pre-war British camps. For a week, the team acclimatized and scouted the route. To manage the harsh winds and reduce gear weight, they chose siege tactics. However, they were digging snow caves instead of using tents for the lower camps, and tried to limit their use of fixed ropes. This kept four climbers together and made planning easier.

Boardman and Tasker on the Rongbuk Glacier in 1982. Photo: Chris Bonington

Establishing camps

On April 4, the party set up Advanced Base Camp at 6,400m after a three-day trek with 13 yaks hauling supplies up the East Rongbuk Glacier. Two more yak trips brought food and gear. The weather was brutally cold, with winds sweeping the glacier.

On April 10, they dug their first snow cave at 6,860m. Two days later, they began digging a second snow cave at 7,300m, but hitting rocks meant they had to work hard for 14 hours over several days to make it habitable. After this slog, they rested at Advanced Base Camp from April 14 to April 18.

Returning to the ridge on April 18, the team occupied their second snow cave on April 20. Over the next two days, they climbed two steep sections: a snow gully and a stretch of broken rock, where they placed their first fixed ropes. Exhausted, the party descended to Advanced Base Camp on April 23 and then to Base Camp for a few days’ rest, as full recovery at 6,400m was nearly impossible. Meanwhile, Clarke and Gordon oversaw yak herders ferrying gear from Base Camp.

On April 29, the climbers returned to Advanced Base Camp in a single day. While Clarke and Gordon attempted Point 6,919 on the Rongbuk Glacier’s eastern side, the climbers returned to the ridge.

On May 1, Boardman and Renshaw reached 7,800m, camping at the top of the snow shoulder. Bonington and Tasker carried food and gas to them before returning to the second snow cave. The next day, all four moved up, and Boardman and Renshaw dug a third snow cave just below the ridge crest.

Tasker, Boardman, and Renshaw on the first pinnacle during the 1982 Everest expedition. Photo: Chris Bonington

Facing the pinnacles

The real challenge began at 8,000m, where the ridge narrowed into a snow crest blocked by rocky pinnacles, stretching 800m and rising 400m to join the North Ridge route used by earlier expeditions. This section promised some of the hardest climbing ever attempted at such an altitude. On May 4, Boardman led a notable climb up the first pinnacle, navigating ice and loose rock with few anchor points. Bonington joined two ropes to give him a 76m run-out, and Boardman fixed another 91m to reach a notch overlooking the ridge’s eastern side.

On May 5, Renshaw took the lead, climbing a steep, unstable snow pitch to 8,200m. While working, he felt a strange tingling down one side of his body. Boardman and Tasker pushed on, reaching 8,230m, but Renshaw’s condition worried everyone. After four nights at nearly 8,000m, the team was drained.

They descended to Base Camp, where Clarke diagnosed Renshaw with a mild stroke and sent him to Chengdu for recovery. Bonington, feeling slower than Boardman and Tasker, decided to step back from the summit push. Instead, he and Gordon would try to reach the North Col at 7,000m to set up a food depot and mark a descent route.

The team from left to right: Chris Bonington, Charlie Clarke, Adrian Gordon, Joe Tasker, Pete Boardman, and Dick Renshaw. Photo: Adrian Gordon/Chris Bonington Picture Library

The final push

On May 13, Boardman, Tasker, Bonington, and Gordon returned to Advanced Base Camp. On May 15, Boardman and Tasker climbed to the second snow cave in just six hours. The next day, they reached the third snow cave, stocked with food, fuel, and 244m of rope.

Meanwhile, Bonington and Gordon attempted the North Col but stopped 90m short on May 16, blocked by a crevasse and a serac wall. That evening, they had their last radio contact with Boardman, who sounded optimistic, reporting that he and Tasker were doing well.

Boardman and Tasker at Advanced Base Camp the afternoon before their final push. Photo: Chris Bonington

On May 17, Bonington and Gordon watched Boardman and Tasker through a telescope from Advanced Base Camp. The pair started early, reaching their previous high point by 9 am. By evening, they had fixed about 200m of rope, mostly on the northwest side, and moved to the eastern side of the second pinnacle, likely searching for a campsite. They missed radio calls at 3 pm and 6 pm, either distracted by climbing or because of a faulty radio. The team last saw Boardman and Tasker at the foot of the second pinnacle, at around 8,300m.

“How far they got beyond this point is not known, but that is where they were last seen,” Doug Scott wrote in The Himalayan Journal.

Disappearance

On May 18, Bonington and Gordon resumed their North Col attempt, scanning the ridge with binoculars. They expected Boardman and Tasker to reappear, as the ridge’s layout forced climbers back into view. Reaching their previous high point, they camped by the crevasse. On May 19, they completed the route to the North Col but saw no sign of their teammates.

By May 20, Boardman and Tasker’s absence was alarming. The short distance they needed to cover before reappearing suggested a fall, likely on the Kangshung side’s steep slopes.

A map showing the route, the pinnacles, and the point where the team last saw Boardman and Tasker. Photo: Chris Bonington for The Himalayan Journal

Clarke returned to Advanced Base Camp from Chengdu, and the team organized a search. Bonington and Clarke trekked 64km from Base Camp to the Kangshung Glacier’s head, arriving on May 27. Scanning the massive Kangshung face, they found no trace of Boardman or Tasker and concluded a fall there would have been fatal.

Gordon stayed at Advanced Base Camp until May 28, watching the ridge, but saw nothing. The team returned to Base Camp, hoping against hope that Boardman and Tasker might appear, but they did not.

Waiting for Boardman and Tasker on the Northeast Ridge of Everest, 1982. Photo: Chris Bonington via boardmantasker.com

Aftermath

Clarke carved a memorial plaque and placed it on a cairn above Base Camp near the Mallory and Irvine memorial. They assumed Boardman and Tasker had fallen from around 8,300m.

Boardman’s body was found ten years later, in the spring of 1992, by Kazakh climbers on the Northeast Ridge at approximately 8,200m, near the second pinnacle. According to Elizabeth Hawley’s notes in The Himalayan Database: “On the Northeast Ridge, Kazakhs found a tent with two sleeping bags, a stove, an ice hammer, a book with Chris’s name in it, and a diary with May 1982 entries. They took photos of a body near these items. On the breast of the down suit were logos with an outline of a mountain and three letters, one of which was an M. They brought down the book and the diary.”

Boardman’s body was identified by the clothing and the equipment. The Kazakhs found him lying on his back in the snow, relatively intact, with no clear signs of a major fall. Maybe he collapsed and succumbed to hypothermia or exhaustion. The Kazakh climbers left the body where they found it.

Tasker’s body has not been found.

The Boardman Tasker Memorial at Everest Base Camp, with Everest in the background. Photo: Heavywhalley.wordpress

So close to success

The 1982 British Everest expedition was a bold attempt to climb one of Everest’s toughest routes.

“We had been so close to success, had worked harder, and had been more stretched both physically and mentally than ever before. We were united in what we were doing, and until the tragedy, it was the happiest expedition any of us had been on,” Bonington wrote in his expedition report in The Himalayan Journal.

Boardman and Tasker’s legacy endures through their climbs and writings. Boardman’s The Shining Mountain and Tasker’s Savage Arena offer vivid accounts of their adventures and insights into why they climbed.

The Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature was established in 1983 in their memory.

The entire East-Northeast Ridge route was finally climbed to the summit in 1995 (and descended by the same route) by members of the Nihon University expedition from Japan led by Tadao Kanzaki, supported by 35 Sherpa porters. This expedition fixed ropes across nearly the entire route and used supplemental oxygen.

Joe Tasker and Pete Boardman. Photo: Pete Boardman