Much has changed in the 70 years since Makalu and Kangchenjunga were summited for the first time. Yet the mountains have kept part of their allure, despite commercialization. Also, the first ascents had more in common with the modern commercial climbers than one might think.

According to the latest update from Nepal’s Department of Tourism, up to April 16, there were 54 permits for Makalu and 41 for Kangchenjunga. This is less than the 66 permits for Annapurna, the 80 for Ama Dablam, and, of course, the 311 for Everest.

This year, both peaks celebrate the 70th anniversary of their first ascents. Some interesting comparisons exist between the big national teams of the 1950s and the climbers on the mountains today.

70 years ago…

George Band and Joe Brown of the UK first summited Kangchenjunga on May 25, 1955. (Band was the youngest member of the British team that first climbed Everest two years earlier.) Norman Hardie and Tony Streather topped Kangchenjunga a day later. When they reached the top, they respectfully stopped a couple of meters before the highest point out of deference to the local communities, who consider the mountain sacred. Other early expeditions followed that custom, but it slowly vanished.

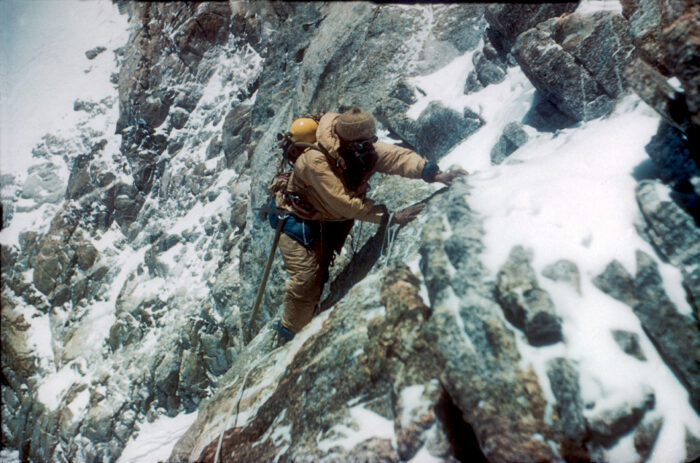

George Band on summit day on Kangchenjunga, 1955. Photo: The Alpine Club, which currently features an exhibition about the climb.

Makalu was summited for the first time on May 15, 1955, by Lionel Terray and Jean Couzy of France. Again, both had been members of the 1950 expedition that achieved the first ascent of an 8,000’er: Annapurna. The following day, team leader Jean Franco, Guido Magnone, and Gyaltsen Norbu also topped out. At the time, it was an impressive number of summiters. It was a common strategy in that era to work jointly on the mountain and finally let the fittest members (usually two) launch the final push to the summit.

The 1950s were the years when peaks were “conquered, ” so the big national teams described their ascents. The goal was to plant a national flag on the summit before anyone else, using all available resources. In that sense, it was not that different from today. The interest in style, difficulty, and self-sufficiency only began 20 years later.

Jean Couzy on the summit of Makalu in 1955. Photo: Summitpost

Makalu and Kangchenjunga were both climbed with the help of oxygen and local Sherpas, although most Nepalese at the time lacked the equipment or experience to reach the upper slopes. This only highlights the accomplishments of the few who did, such as Gyaltsen Norbu on Makalu or Dawa Tensing on Kangchenjunga. Dawa had also been a member of the 1953 Everest team and reached the South Col twice.

The first no-oxygen ascent of Kangchenjunga didn’t occur until 1979, when Doug Scott, Pete Boardman, and Joe Tasker of the UK climbed a new route from the north side. On Makalu, the first no-O2 climber was Marjan Manfreda, part of a Slovenian team that climbed the south face in 1975.

… And now

Nowadays, the use of supplementary oxygen is widespread on the 8,000’ers, and particularly on the so-called Big Five: Everest, K2, Kangchenjunga, Lhotse, and Makalu. Yet this year on Makalu, a significant number of climbers have said they will try to climb without bottled oxygen.

On Kangchenjunga in 2025, more than half of the permits (15 of 26) went to women, whose presence on the 8,000’ers has vastly increased. However, on Makalu this year, there are 43 men and 11 women.

In 2025, Makalu features several teams, including those from Poland and Kazakhstan, progressing independently, that is, without supplementary O2 or personal Sherpas.

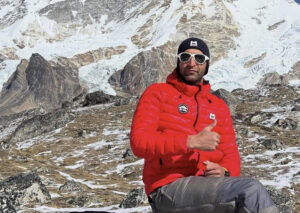

The Kazakh team on Makalu. Photo: Vassiliy Pivtsov

“Independent” teams

In this sense, it is important to clarify that the concept of “independent” teams has been diluted in the last decade. Everyone, including those groups, follows the normal route once it has been opened and ropes fixed by professional Sherpa climbers. This was completed particularly early on Makalu this year, where Lakpa “Makalu” Sherpa and his team summited on April 10.

Finally, no technology or comfort can spare climbers from the wind, a typical characteristic of Makalu. Its normal route is relatively safe from objective dangers but exposed to relentless winds that increase risk of frostbite, and result on long sections of hard snow or ice.

Most Makalu climbers have done a rotation to Camp 2, as shown in the video below, filmed by Jarek Zdanowicz of Poland. Zdanowicz then retreated to Base Camp, where he has sheltered from high winds for the last three days.

Kangchenjunga

Most Kangchenjunga climbers reached Base Camp earlier this week. The majority preferred to trek in, as the ups and downs of northeastern Nepal are perfect for acclimatization. However, helicopters are available for evacuations or retreats to town during spells of bad weather. Below, Simone Moro pilots a helicopter while carrying food and gear to Kangchenjunga Base Camp.