Methodical, realistic, and driven, Andrei Vasiliev of Russia has spent years showing that there is still room for new routes on 8,000m peaks. On the Southwest Face of Manaslu this year, he and his team also proved that one can do it alpine style, in a single push on-sight in unknown terrain, both on the way up and the way down.

Vasiliev and teammates Sergey Kondrashkin, Vitaly Shipilov, Kirill Eizeman, and Natalia Belyankina have won praise from the climbing community, including the Russian version of the Piolet d’Or that they picked up last weekend. The climbers spoke to ExplorersWeb about the expedition.

Route topo of the SW Face of Manaslu, as seen from the glacier. Photo: A. Vasiliev

Cho Oyu test

For Vasiliev, the project started two years ago on the South Face of Cho Oyu, where he attempted a new route in 2023 and the SSE ridge route of 1991, in 2024.

“The Cho Oyu experience was essential to fully understand our capabilities during long periods at high altitude,” he explained. “[It showed] our technical climbing skills above 7,500m, and all the health issues we might face. We prepared for Manaslu accordingly.”

Without that testing, he doesn’t think they would have dared try alpine-style climbing on such a remote face, with so little information about the terrain.

“Thanks to Cho Oyu, we reached Manaslu knowing well how we would feel on the 10th day of the ascent at 7,400m,” he explained.

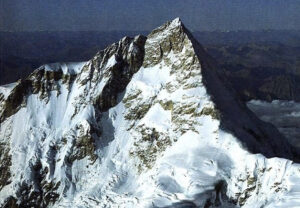

The ridge leading to the final headwall on Cho Oyu’s Southwest Ridge route. Photo: Andrey Vasiliev/RAF

“Physically, this climb on Manaslu was not as hard as our 2024 attempt on the South-Southwest Ridge of Cho Oyu,” Vasiliev pointed out. “This time, we started the climb in good physical condition.”

In addition to good training, the team wisely acclimatized on the normal route of Manaslu.

“This way, we saved a lot of resources. Last year, by the time we launched the final attempt, we were already exhausted.”

More members needed

They also discovered that their Cho Oyu team was too small, so they added members accordingly.

“At such a high altitude, we can’t expect anyone to rescue us, so we need at least four members to be self-sufficient and able to do rescues independently in case of an accident,” Vasiliev said.

He explained that two months before Manaslu, not everyone from past Cho Oyu expeditions was ready for another Himalayan ascent.

“Not all of us are professional climbers,” he said. “We have ordinary jobs that we cannot easily skip for two months. One must also bear in mind that a member may drop out at the last minute. We needed an extra member just in case and found Natalia [Belyankina].”

“She has vast experience in high-altitude climbing in Kyrgyzstan and Tadjikistan, and enough experience in technical climbing,” Vasiliev said. “In addition, she is a very pleasant and positive person to deal with. She was the new member, but fit immediately into the team.”

Enjoying the sun. Photo: Serguey Kondrashkin

Lost toes

In 2022, Natalia Belyankina became the youngest woman to ever complete the demanding Snow Leopard challenge (summiting the highest peaks of the former USSR, all of them in Central Asia). The achievement came with a price: She lost some toes to frostbite and had to learn to walk again. That didn’t affect her determination to return to high altitude.

“My team stopped seeing me as special or fragile long ago,” she wrote on social media during the expedition. “They just joke that now we have someone who can’t get frostbite on her toes.”

Belyankina told ExplorersWeb that climbing an 8,000’er was a dream come true. She had ample experience at 7,000m, but how would that translate to peaks 1,000m or more higher?

“It turned out that I can indeed climb 8,000m peaks without supplemental oxygen and carrying a 30kg backpack,” she said. “That means that I can now seriously consider doing another.”

Natalia Belyankina on the flat section of the Thugali Glacier. Photo: A. Vasiliev

8,000m on a shoestring

Not only the climb, but the entire expedition, was unusual in its simplicity, particularly on Manaslu, one of Nepal’s most popular 8,000m peaks in autumn.

Most fly into Manaslu Base Camp, but the Russians trekked from Tilicho via the Larka La pass (5,106m) to Samagaon. Here, they stayed in a lodge, which was cheaper than hiring logistics in Base Camp, one day away.

“This year, the Manalsu permit rose in price from $900 to $3,000, so we had to save money in other ways,” Vasiliev said.

The lower altitude of Samagaon allowed them to recover better during rests. They acclimatized on the normal route of Manaslu for 11 days, and then started walking.

“We had some luggage carried by porters in both directions, although we could only find three porters (we needed six) from Tilicho to the Southwest Side of the mountain, as our dates coincided with national festivities.”

The three porters had to do two trips to Dona Lake. From there, the climbers shuttled their loads to Base Camp over three days.

Base Camp. Photo: Andrey Vasiliev

Choosing the line

They had three potential climbing lines in mind, depending on conditions. However, in strict alpine style, they could only set foot on the route during their summit push.

“We tried to use a drone, but our lack of experience did not allow us to get any significant information,” Vasiliev said. “The drone fell before even reaching the icefall.”

The lower part of the route. Topo and photo by A. Vasiliev

The original goal was to attempt a direct route up the center of the Southwest Face. However, as Vasiliev explained, the right part of the wall leading to a steep rock tower would have taken too much time.

“All the other possible lines largely consisted of snow and ice sections, so it was essential to assess the snow conditions correctly,” Vasiliev said.

The team checked the information available in The Himalayan Database. They noted that many previous attempts had taken place in September. All reports mentioned bad weather.

“However, the big snowfall typically seen at the end of the monsoon fell this year between September 30 and October 7 and was not as abundant as in previous years,” Vasiliev explained. “We left Base Camp five days after the last precipitation, hoping there wouldn’t be too much snow on the face. And indeed, we found nearly perfect conditions.”

Often, the southwest slopes, the icefall, and the flat part of Thulagi Glacier are highly avalanche-prone.

“We constantly monitored the weather forecasts, and were very lucky that the whole time we were on the mountain, there was nearly no snowfall.”

The line they finally chose runs about 1,000m to the right of the Tyrolean route that Reinhold Messner opened in 1972. A big rocky section separates both routes. So the new Russian line goes up completely new terrain.

The climb

“Our route didn’t have any clearly defined cruxes,” Vasiliev pointed out. “But overall, it’s very demanding. One of the main challenges was to protect our progress. Except for some isolated spots, there was no reliable ice on the face, so the only protection was deadmen [snow anchors].”

Technically, the most difficult part was a mixed section at 7,500-7,700m, consisting of short rock steps and steeper snow and firn slopes, explained Vasiliev.

In his diary excerpts below, Vasiliev matter-of-factly describes the climb, making it sound like a moderate line at a crag. It was not.

Diary

October 12. We left Base Camp with very heavy backpacks (32 to 35kg each).

October 13. After two hours, we reached the bottom of the icefall and studied the maze of seracs for the least risky line. The only option was up its left side, then to cross in the middle, and climb the upper headwall via a rock ridge. Some previous expeditions used fixed ropes on the rocky sections or up the right side of the icefall, but that was not an option, since we [were going] alpine style.

October 14: We rose at midnight, crossed the icefall to 5,300m, and camped under the last serac.

October 15: We began to cross the flattish plateau of the Thulagi Glacier. Meanwhile, we studied the Southwest Face and discussed the best line.

October 16: We made a final decision on the line and started off. Shortly afterward, we set the first camp on the actual face, at 6,300m.

The snow slope before the bergschrund. Photo: A. Vasiliev

October 17: We began climbing the Southwest Face, up snow slopes of 30 to 55 degrees, mainly simul-climbing. We bivvied at 6,900m, right before a serac area.

October 18: Early in the morning, we crossed the dangerous serac zone. At 10 am, we reached a bergschrund where we had to camp, because the long, steep slope that came next had no visible bivouac places.

On a mixed section at 7,600m.

October 19: We set off, removing the ropes as we climbed, and then went further up a 60º snow slope. It was hard to protect that section. We had plenty of snow and ice gear, but nothing worked well, and progress was slow.

By midday, the wind grew stronger, and small powder avalanches started falling from a rocky section above us, just where we intended to climb. For that reason, we changed course and opted for a longer but safer route up a snow slope leading to the right.

There was no proper place for a tent, so we had to cut a platform out of the steep slope at 7,400m. The shelf was about 1-1.5m deep and 3.5-4m wide. We stretched the tent overhead for wind protection and covered ourselves with a synthetic blanket (we carried no sleeping bags, only our down suits and this blanket). It provided a safe but very uncomfortable night. Only when the sun came out were we able to move around.

On the final summit ridge. Photo: A. Vasiliev

October 20: It was already 11:30 am when we resumed the climb. That day, we climbed only four pitches.

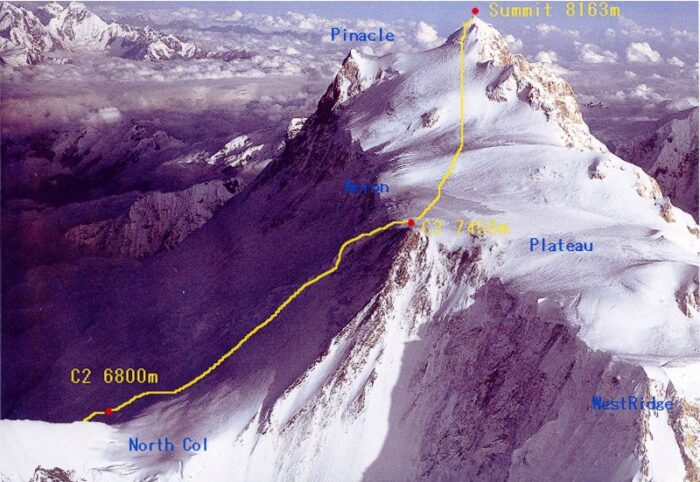

October 21: We climbed the most technical section of the route, on mixed terrain, and reached a high plateau at 7,730m. Here, our line merges with the classic and Tyrolean routes. Note: both the Tyrolean route from the southwest and the normal route from the northeast side of Manaslu join a high plateau at 7,400m. The plateau then narrows progressively until it becomes a ridge, eventually leading to the highest point.

The high plateau leading to the summit of Manaslu. The normal route (in yellow) reaches the plateau from the northeast, while the Tyrolean route does the same from the opposite side of the mountain.

October 22: After climbing the Southwest Face, we expected this last part to be an easy walk to the summit, but high winds made reaching the summit tricky. Up to the summit ridge, it was sort of okay, since we were partially protected from the wind by the terrain, but it was really hard on the ridge. We finally reached the summit, one by one, at 3:53 pm and then returned to our bivouac site at 6:30 to 7 pm.

October 23: We started descending pretty late, at around 4pm. We reached the bottom of the plateau, approximately at 7,350m. We knew the Tyrolean route was somewhere nearby but we could not find it due to low visibility.

During the descent. Photo: A. Vasiliev

October 24: We [found] and descended the Tyrolean route. We rappelled down five pitches and fixed a rope to descend down 15 pitches more. Four of us used it to go down, and the last in line would retrieve the rope and downclimb. We bivouacked that night at the pass between the Thulagi Glacier and Manaslu, at about 6,500m.

October 25: We climbed down the flat glacier to 5,800m. There, we saw that our ascent path was still visible. By then, we had almost run out of food.

October 26: We crossed the upper part of the icefall (including one rappel down the rock section). By then, many more crevasses had opened, but all of them could be walked around or jumped over. We waited for the sun to go down before crossing a dangerous part in front of us, a slope below a large couloir, and continued down to the bottom of the icefall. At 8 pm, we finally reached the point that had been our Advanced Base Camp on the way up.

October 27: We ate our last remaining raisins in the morning and finally arrived back in Base Camp at around 5pm, tired but happy. We made dinner and celebrated the end of our long climb with some beer!

Notes on the descent

During the climb, short texts from the team indicated they had been in trouble during the descent due to a whiteout. However, Vasiliev explained the descent was not too troublesome, because after the first day of descent, when visibility was poor, they had a clear day and found the right path.

“If the visibility had remained bad and we couldn’t find the Tyrolean route, we had a backup plan to descend the normal route to the other side of the mountain,” Vasiliev explained. “What was definitely not an option was to retrace our steps down our ascent line. It was much longer, higher (it has 600 more vertical meters on the face), and also includes a dangerous area full of seracs.

‘Just technical work’

The climbers remain humble about their achievement.

“Our ascent is not of great importance in the history of mountaineering in general,” Vitaly Shipilov told ExplorersWeb. “It is just another of many routes climbed on known mountains. We did not discover a new peak; we just climbed it from the other side.”

Shipilov did admit that the climb was important for him personally.

“It is the result of long preparation, unsuccessful attempts, risks, and hard work,” he said. “I am satisfied with the result we achieved, but awards are not important. My most vivid memory is the incredible beauty during our time there, the way we interacted, had fun, and helped each other…Everything else is just technical work.”

Climbing a rock section at 5,600m. Photo: A. Vasiliev