In 1967, Mount McKinley (Denali) witnessed two pivotal moments in mountaineering history.

In Part I of this series, we told the story of McKinley’s first winter ascent. Later that same year, during the summer season, the mountain saw one of the worst tragedies ever on a North American peak. This is the story of the 1967 summer season on McKinley.

(Writer’s note: Following the Associated Press style guide, I will use the name McKinley in these pieces.)

A record number of ascents

In 1967, 10 expeditions attempted Mount McKinley, making it the most successful year on record. Almost all of the expeditions’ members topped out.

In summer, two teams aimed to summit via the remote Muldrow Glacier route, first ascended by the McKinley pioneers in 1913. The Muldrow Glacier route is considered more difficult than the West Buttress route for logistical and technical reasons.

The route begins on the north side of McKinley and requires a 63km trek from Wonder Lake to the base of the glacier. From the base near McGonagall Pass at 1,750m, climbers gain 4,440m to McKinley’s summit at 6,190m. The Muldrow Glacier features complex glacier travel in heavily crevassed terrain, usually requiring constant roped navigation.

The key section of the route, Karstens Ridge is a narrow, exposed ridge that joins the Harper Glacier, adding more crevasse hazards. The ridge is also particularly vulnerable to high winds. Unsurprisingly, the 1951 West Buttress route became the common route up McKinley rather than the tricky Muldrow Glacier-Karstens line.

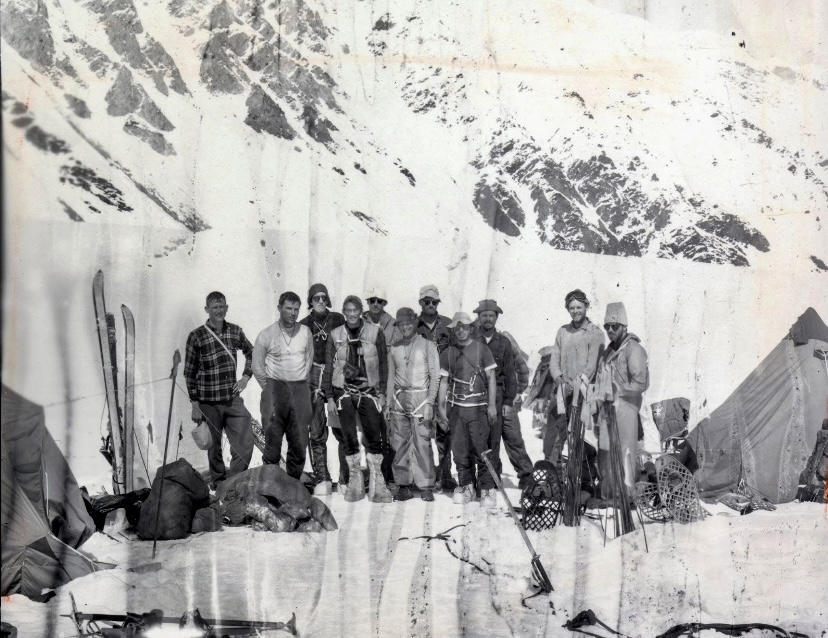

The 1967 summer expedition on McKinley. Photo: Howard Snyder

Wilcox expedition

The Wilcox expedition, led by 24-year-old Joe Wilcox from Utah, was the first of the two teams attempting the Muldrow Glacier route. He looked for climbers to join him via climbing newsletters. His party eventually included nine members: Wilcox, Jerry Clark, Steve Taylor, Dennis Luchterhand, Mark McLaughlin, Anshel Schiff, Hank Janes, John Russell, and Walt Taylor.

It was a young group, with everyone between 22 and 31 years old. Most came from the Pacific Northwest. They all had basic mountaineering skills but hadn’t climbed higher than 4,550m.

Colorado expedition

Howard Snyder, 22, led the Colorado expedition, the second team on that route. With Snyder were Jerry Lewis, Steve Lewis (Jerry’s brother), and Paul Schlichter.

Like the Wilcox group, this was a young team. However, Snyder and his partners had more mountaineering experience and had climbed at higher altitudes.

Just before their departure on June 21, the team was reduced to three when Steve Lewis broke his arm in a car accident.

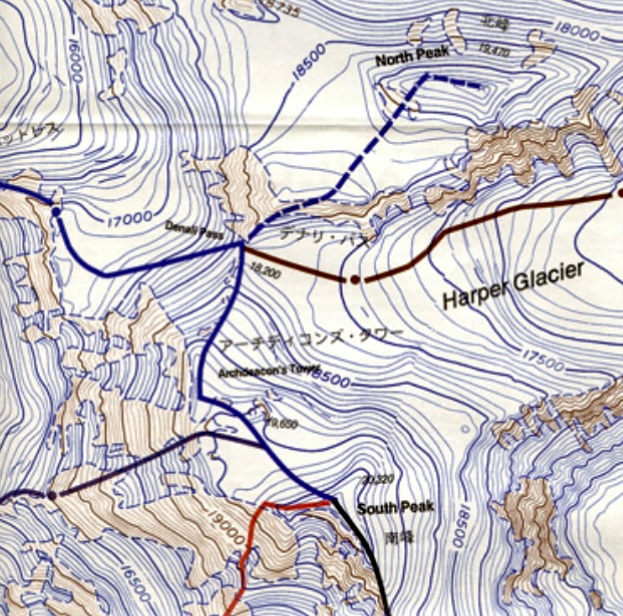

The Muldrow Glacier route (marked in brown). Photo: Cliffhanger76

The National Park Service (NPS) was skeptical about the Wilcox expedition because of its limited high-altitude experience. They suggested Wilcox merge his group with Snyder’s party. Thankfully, this also suited Snyder because NPS rules stated there should be at least four members in an expedition group. The merger occurred on June 22, and Wilcox took command of the 12-person team.

July 16: the key day

The merged group started their trek in from Wonder Lake. In early July, the climbers made steady progress, establishing camps and ferrying supplies. Most of them experienced altitude sickness but tried to adapt. By July 13, the group had set up camp on the Harper Glacier.

On July 15, Wilcox, Snyder, Schlichter, and Lewis started a summit push from their high camp at 5,456m. They reached the summit at 6:30 pm in good weather, with a clear sky and light winds. After spending over an hour on top, they descended to high camp by 9:50 pm.

On July 16, all 12 members were at high camp when 113kph winds picked up, forcing everybody to remain at camp. This temporarily stalled plans for a second summit push by Clark, Luchterhand, McLaughlin, Janes, Russell, and the two Taylors.

The Muldrow Glacier-Karstens Ridge route on Mount McKinley. Photo: Haisam Hussein

The second summit bid

Park rangers reportedly warned Wilcox of an approaching storm. They projected it would hit around July 16 or 17, but the group continued with their summit plan, perhaps underestimating the storm’s severity.

On July 17, the second group, led by the 31-year-old Clark, went for the summit. The group that had summited two days earlier descended to a lower camp at 4,572m.

The wind had subsided as Clark and company set off. Steve Taylor remained at high camp because of altitude sickness. That night, strong winds started on the upper slopes. The summit group stopped to bivouac, hoping for better weather the next morning.

On July 18, at 11:30 am, Clark radioed to say that he, McLaughlin, Walt Taylor, Janes, and Luchterhand had topped out in a whiteout. John Russell’s situation was unclear; he didn’t summit and might have turned back during the push.

Clark said that they would start to descend in 10 minutes. They never radioed again.

Howard Snyder on the summit of McKinley. Photo: Howard Schlichter

The biggest storm in 100 years

The storm kept getting worse. A high-pressure system from the south clashed with a moist low-pressure system from the north, creating the biggest storm ever recorded on the mountain. It would last seven days, to July 25.

Near the summit, the wind was 160–240kph, with still-air temperatures of -26ºC.

Those below the summit, on the upper section of McKinley, were trapped. The other members, who had already descended from their summit bid, spent the seven-day storm at a lower camp. They tried to stay warm by huddling together.

McKinley, 1967. Photo: Howard Snyder

The seven climbers higher up had no chance of survival. Jerry Clark (31), Steve Taylor (22), Dennis Luchterhand (24), Mark McLaughlin (23), Hank Janes (25), John Russell (23), and Walt Taylor (24) all died. The five climbers at the lower camp made it down alive after the storm ended.

Several days after the storm, two bodies were found at Archdeacon’s Tower below the summit. The NPS located another body at high camp holding a tent pole. Their bodies could not be identified because of decomposition. The other four climbers were never located.

The three bodies were left on the mountain. In 1968, an expedition tried to find the victims but found no remains.

Conclusions

The original Wilcox team had no proper high-altitude experience. Experienced alpinists might have better gauged the risk or built snow caves.

Another problem could be that the team divided on the mountain after the first summit on July 15. This split the stronger climbers (who had already summited) from the less experienced climbers.

Later, Snyder criticized Wilcox for this split. Wilcox defended the split as a chance for everyone to summit, but Snyder argued that it weakened the team’s ability to respond as a unit. As a merged group, the team lacked cohesion.

The rangers’ warning about bad weather is also key. Wilcox claimed the notice he received was vague and didn’t mention how fierce the storm would be.

The tragedy was the result of an extraordinary natural event and human decisions that amplified the risk. Seven relentless days caused exhaustion and hypothermia. National Weather Services later called the storm a once-in-century event. Possibly no team, regardless of skill, could have faced it effectively high on the mountain.

This was less about gross negligence and more about the limits of human judgment against nature’s extremes. McKinley’s power was unforgiving.

The Harper Glacier from the Karstens Ridge on McKinley. Photo: Summitpost

Comparing the 1967 winter and summer expeditions

It is interesting to compare this summer expedition with McKinley’s first winter ascent from February of the same year. Gregg Blomberg’s winter party had much more experience and enough collective knowledge to handle extreme conditions.

The winter team’s decision to construct an ice cave below the summit was pivotal. The small cave was an important shelter that protected them from the worst of the wind. However, the July hurricane was much stronger than the February storm.

Mental strength is another important factor in a week-long hurricane at high altitude, in subzero temperatures, with frostbite setting in. Only strong mountaineers are capable of thinking clearly in these circumstances. Most people without experience on high mountains simply can’t react as assertively.

Luck

Luck also plays a major part. It was pure chance that the storm arrived during the July team’s most exposed moment. Weather forecasting in 1967 could not predict its exact onset, and the rangers’ warning didn’t pinpoint the critical hours. The five who summited earlier, on July 15, were lucky to have made it to the top. By making it down in time to a lower camp, they missed the worst days.

However, it’s important to listen to the mountain and retreat when there are signs of changing weather. The key day was when all 12 members were at high camp, trapped by the weather, with the July 15 summiters unable to descend and the rest of the team unable to ascend.

Aftermath

The 1967 tragedy led Denali National Park to modify climbing protocols, including requiring parties to register in advance, document their mountaineering experience and readiness, carry two-way radios, and contact park officials when the climb is over.

The 1967 team. Photo: Denali National Park and Preserve