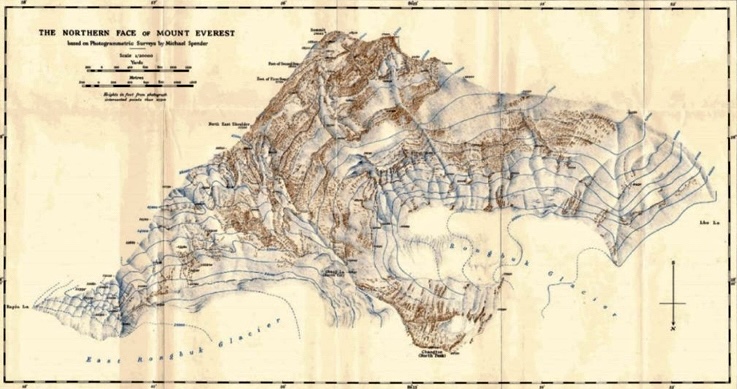

British surveyor Michael Spender created the first detailed photogrammetric map of Mount Everest’s North Face in 1935 using 1,200 aerial photos and ground measurements. His map guided major British Everest expeditions for North Face approaches for years.

Early years

Michael Alfred Spender was born on November 11, 1906, in London. His father, Harold Spender, was a Liberal journalist and biographer. His mother, Violet Schuster, was a painter and poet of German-Jewish descent. Violet died of influenza in 1921, when Michael was 14.

Spender attended Gresham’s School, then Balliol College, Oxford, graduating in engineering in 1928. He never joined the Alpine Club or pursued climbing for sport. For him, mountaineering was merely the means to an end: accurate surveys of high places.

From 1928 to 1929, he mapped Australia’s Great Barrier Reef with the Royal Geographical Society, living on the survey launch for 18 months. In 1932 to 1933, he surveyed East Greenland’s fiords using overlapping aerial photos, aiding British territorial claims.

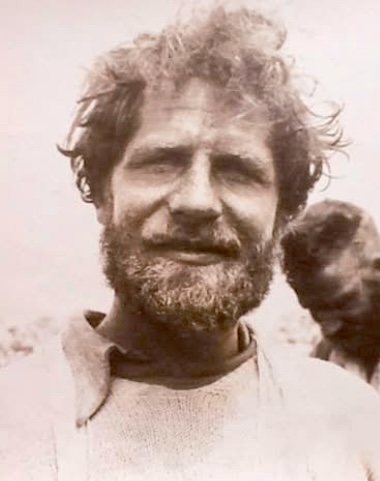

Michael Spender. Photo: Olive Edis/National Portrait Gallery

The 1935 Everest mission

Earlier surveys of Everest existed; for example, those conducted by Canadian surveyor Major Edward Oliver Wheeler, who played a pivotal role in the 1921 British Mount Everest Reconnaissance Expedition. Wheeler’s photos aided Spender’s work, but Spender further evolved the photogrammetric technique, which uses overlapping images to give 3D images and precise measurements.

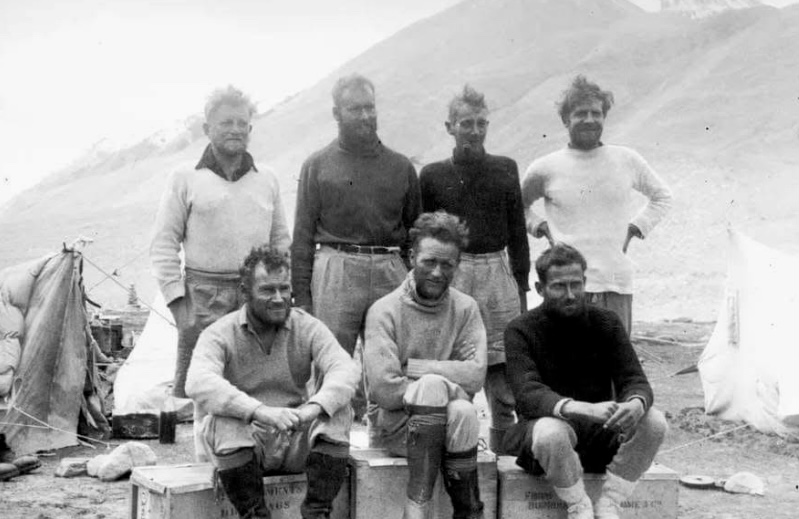

After the 1924 Everest tragedy with George Mallory and Sandy Irvine, the Mount Everest Committee demanded a new North Face map. The Royal Air Force loaned the 1935 Everest expedition two Houston-Westland biplanes, and Spender was the chief surveyor. The team included leader Eric Shipton, Bill Tilman, Edmund Wigram, Charles Warren, and porter Tenzing Norgay, who was only 21 years old at the time. The team was completed by Dan Bryant, Edwin Kempson, and 11 Sherpas. Spender had only three weeks for the preparation.

Open cockpit

A theodolite precisely measures horizontal and vertical angles. It has a telescopic sight, two rotating circles (one for azimuth, one for elevation), and a leveling base. Surveyors sight a target, read the precise angle in degrees/minutes/seconds, and triangulate positions from that angle. Spender used two types. The heavy Wild photo-theodolite was 18 kilograms, including a camera, for base control. The portable Watts-Leica for high camps was 8.6 kilograms.

Biplanes flew at altitudes of 8,200 to 8,800m. Spender sat in an open cockpit, directing 1,200 overlapping photos. As he emphasized, the single photograph gives a flat picture; the stereo pair restores the three-dimensional form of the mountain. Spender was convinced that this was the key to accurate contouring.

The members of the 1935 Mount Everest expedition. Back row, left to right: Bryant. Wigram, Warren, Spender. Front row: Tilman, Shipton, Kempson. Photo: L.V.Bryant/RGS

Maurice Wilson’s body found

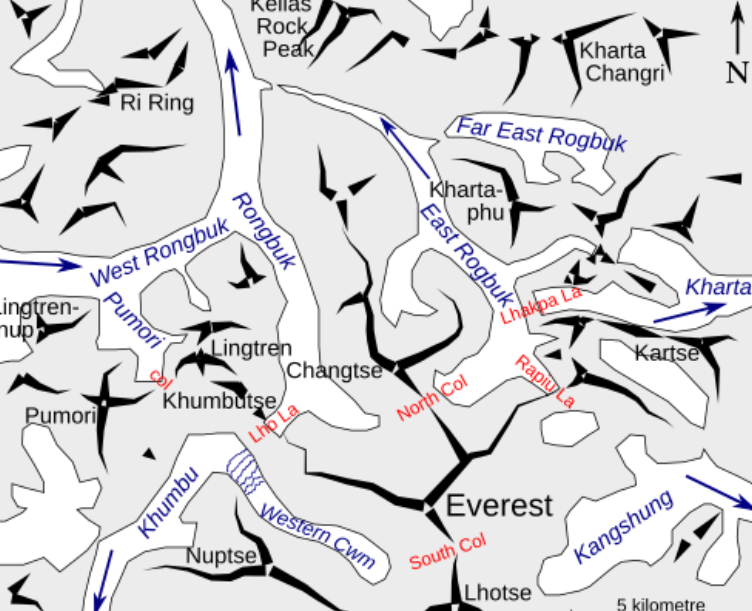

Spender established six primary stations at 6,100m at the high pass known as Lho La, linking aerial photos to fixed points recorded in 1921. With Sherpa assistants, he crossed the icy Rongbuk streams at dawn.

“We forded the glacier-fed torrents at 4 am before the afternoon rise. By 7 am, the water was waist-deep and dangerous,” Spender recalled. He mapped two previously unmapped eastern valleys near Base Camp: “The quarter-inch maps were out by half a mile in places. We corrected them with the Watts-Leica from 5,500m.”

Spender trained Shipton, Kempson, and Warren to use the Watts-Leica. They surveyed the East Rongbuk Glacier toward 7,035m Kharta Changri, setting “Spitsbergen Camp” beyond a 30m ice cliff. While advancing to Camp 3 up the East Rongbuk Glacier, Warren discovered the frozen body of Maurice Wilson, the solo climber who had perished the previous year, before the team continued on to Kharta Changri.

Spender stated that a mountaineer can become a skilled geographer because with a light instrument, he can fix his route and map it simultaneously.

The new large-scale map of 1935, published by the Royal Geographic Society based on Spender’s survey.

Spender’s accuracy

Persistent clouds blocked the expedition. Spender got sick on Lho La, and Sherpas carried him down, but he insisted on finishing the survey. Spender stressed that the ground control could not fail. The aerial photos were useless without it.

After the expedition, back in London, he began the data processing. He used a Wild A5 stereo-plotter and shipped negatives to Copenhagen, where an expert plotted the initial contours. Then Spender integrated the 1921 Wheeler photos, the 1933 Houston flight’s obliques, and Captain Crone’s graphical method for the heights of Makalu and Chamlang peaks.

Spender’s accuracy was notable. His contours proved remarkably consistent with later surveys. Shipton praised Spender’s work and, in his book Blank on the Map, claimed that Spender gave them a map they could trust.

In his report for the Himalayan Journal, Survey on the Mount Everest Reconnaissance, Spender laid out his philosophy. He believed in the need for preparation. For him, the stereo method worked much better than the plain-tabling, because, in his opinion, plane-tabling was laborious and lost accuracy above 6,000m, while the stereo method gave a model from which contours flowed naturally.

He noted that the climber’s involvement was also important. For him, the future of Himalayan cartography lay with the mountaineer-surveyor. With a light theodolite and camera, the mountaineer-surveyor could map as he climbed. Thanks to his surveying work of 1935, the North Face of Everest became known within 15 meters in every detail.

“The 1935 survey proves that photographic methods, properly controlled from the ground, can replace all older techniques in high mountains,” wrote Spender. His final report included a 1:12,500 map published in the Geographical Journal, with 15-meter contours. Every ridge, couloir, and icefall was rendered with unprecedented clarity.

A modern diagram of northern approaches to Everest. Photo: Wikimedia

Later mapping

In 1937, Spender rejoined Shipton in the Karakoram. He crossed a mountain pass, later renamed Spender’s Pass, with Sherpas. In 1939, at the Wild factory in Switzerland, he compiled the unpublished 1:50,000 Environs of Mount Everest using 1935 film and plates. It covered 350 square kilometers around Everest and 450 square kilometers in the Sar area, with 100m contours.

Lost for over 50 years, it was rediscovered at the Royal Geographic Society, scanned, and featured in the Geographical Magazine. It later informed G.S. Holland’s 1961 1:100,000 map.

War service and death

In 1939, Spender joined the Royal Air Force, working on photo interpretation. He built a 3D stereoscope that located V-2 sites, aiding the 1943 Peenemünde raid. He also spotted D-Day beach obstacles. In 1944, he was promoted to Squadron Leader.

On 3 May 1945, his Avro Anson plane crashed near Süchteln, Germany, after engine failure. With a broken chest and punctured lung, he died in a hospital on May 5, at age 38. He is buried in Eindhoven Cemetery.

A complex character

Spender’s brother, Stephen, who was a poet, saw Michael “cold and sharp.” Early friction, especially with John Auden in the Karakoram, came from Spender’s intensity. “His apparent arrogance was the mask of a man who demanded precision in himself and others. Once understood, he revealed a rare humility and generosity.”

Spender’s drive was intellectual, and not ego-driven. He trained climbers not to impress, but to empower them. “The surveyor should not be a burden. He must make the climber his own geographer,” wrote Spender.

His brother Stephen wrote in his World Within World: “Michael was always the clever one, cold and sharp in manner, but with a mind like a steel trap. He had little patience for sentiment.”

Stephen’s portrait revealed the complex character of Michael Spender: He was brilliant, exacting, and sometimes aloof. However, those who worked closely with him saw deeper layers. Shipton, in his 1946 Alpine Journal obituary, addressed the contradiction: “To some, he appeared arrogant and overbearing, but those who came to know him found energy, enthusiasm, originality, and an underlying humility that made him the ideal companion for exploratory trips.”

Michael Spender. Photo via Dawn

Legacy

Spender’s 1,200 photos, dozens of ground stations, and stereo-plotting created a map accurate to 15 meters, and his report remains a foundational text in high-altitude cartography. Spender elevated surveying from a side task to a core scientific contribution in exploration.

As Shipton noted, Spender’s work in the development of survey methods for use in mountainous country, and his own application of them in the field, did much to raise the standard of exploratory survey from a subsidiary role to one of major importance. He was one of the pioneers in this field.