In the 1980s, exploratory alpinists Mick Fowler and Victor Saunders stunned the climbing community when they first climbed the Golden Pillar of Spantik. Fowler described their difficult line as the Walker Spur of the Himalaya. Last fall, their excellence showed again at ages 68 and 75 when they executed a flawless first ascent in pure alpine style of 6,258m Yawash Sar in the Karakoram.

The summit of Spantik, 1987. Photo: Mick Fowler

The two veterans plan to introduce themselves as the “Pioneering Pensioners” at a lecture hosted by the Mount Everest Foundation at London’s Royal Geographical Society on March 27. Recently, they spoke with ExplorersWeb from Chamonix and Derbyshire. Fowler and Saunders have endless stories about their climbs, including important life lessons about adventure and friendship.

Period of separation

Mick Fowler, 68, is a retired tax inspector and a cancer survivor. Yet he has never stopped climbing. Saunders, who left his architect’s career at 45 to become a professional mountain guide in Chamonix, is still leading ski tours at 75.

“The clients probably freak out when they find out they have such an old guide,” Fowler chuckles.

Saunders offers a different version: “I am trying to retire, but my lovely clients won’t let me,” he says.

In the last five years, the duo commonly known as Vic and Mick have been on yearly expeditions together. Friends since their youth, they were nevertheless separated for decades.

“We often climbed together between the 1970s and the 1990s, but then Victor moved out to Chamonix, and I stayed in London, so we lost touch for nearly 30 years,” Fowler said.

They met again during the research for a book by Eric Vola about their pioneering Himalayan climbs.

“We got together and thought, oh, we really ought to do some climbing together again,” Saunders said. “So in 2016, we did the first ascent of the north buttress of Sersank (6,100m) in the Indian Himalaya.”

It was their first expedition together since 1987, but it felt like time had not passed them by.

“It was such a fantastic trip [that] we decided we should really carry on…as we seemed to be really enjoying ourselves,” Fowler noted.

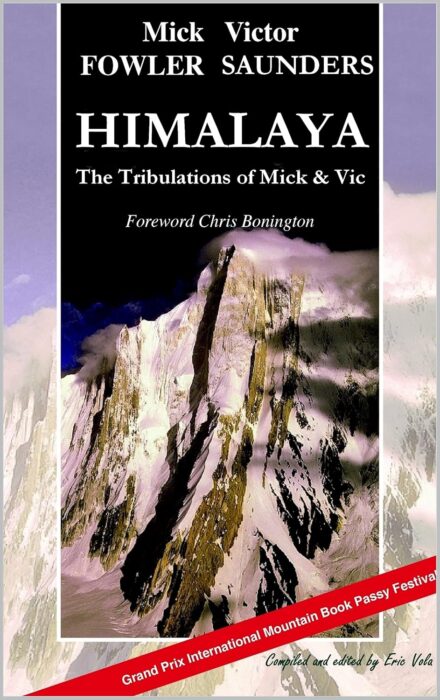

The book about Fowler and Saunders’ Himalayan climbs.

“The really interesting thing is that at the end of our working careers, we rediscovered that we still could climb together very well,” Fowler added. “On Sersank, we were probably slower than on our first expeditions, as we were in our 60s by then, but it felt like we were back in our 30s. It was a fantastic discovery.”

The north face of Sersank, 2016. Photo: Mick Fowler

One proper fight

After all this time apart, it is significant that they still got along so well. Some climbing partnerships end in bitter disputes, but that is obviously not the case here.

“We did have a proper fight once, and I don’t know who won, but the people looking on said it was me,” Fowler recalls.

“Excuse me, what did you say?” asked Saunders. “I should explain: There was this pub in London in a very seedy area, which had a boxing ring. Every Sunday, they encouraged customers to go into the ring and punch each other. One day, Victor and I did! Which, of course, provided great amusement for our friends.”

Saunders, left, and Fowler after the first ascent of Fly Dt Creagh Meaghaidh. Photo: Mick Fowler

The two stopped climbing together when Saunders moved to France after climbing together for most of the ’70s, ’80s, and early ’90s. During that time, they set new standards of difficulty at home, especially in Scottish climbing, as well as abroad.

“We continued being friends but otherwise moved on with our individual lives and climbing careers.”

During this hiatus, Fowler often went on expeditions with fellow Brit Paul Ramsden. Together, they won three Piolets d’Or in 2003, 2013, and 2016.

One year after Sersank, Fowler was diagnosed with cancer, which required him to use a colostomy bag. But even that didn’t stop him from climbing. He was back to the Himalaya in 2019. During the COVID lockdown, he studied a photo of a striking pyramidal peak called Yawash Sar in the American Alpine Journal and made plans.

Back to the Karakoram

“It was incredible that the peak was still untouched,” Fowler said. “I did a bit of research years ago, but back then, it was not safe to travel to that part of the world. Then, I saw a chance last year. I revisited my notes, asked around, and found out the peak was quite accessible and safe. It was a good time to go.”

“When you get through the administrative process, permissions, fundraising…and then you cross the bergschund and start climbing, you get a very special feeling,” Fowler said.

Saunders added: “We had to deal with pretty deep snow until after the bergschrund. But the face was so steep that…all the new snow had slipped off, and the climbing conditions were really good.”

Victor Saunders on Yawash Sar. Photo: Berghaus

The worst night ever

The climb was reasonable in difficulty, but the bivy spots were something else. There were no flat spots on the whole route and hardly anywhere to cut a ledge on which to put a tent.

On the first night, they could only pitch half a tent, and they spent the night dangling their legs in the void. The second night, there was nothing at all.

“All we could chop was the size of a chair, and it was sloping,” Saunders said. ” It was a miserable night, one of the hardest I’ve spent on a mountain, windy and cold. We put the tent fabric on our heads, but without the poles, it didn’t really protect us from the wind. It was one of those nights when you are really glad to see the dawn.”

“We were sliding down all night,” Fowler said. “It was especially hard for me since the treatment for cancer involved removing most of the fat in my buttocks. That means I have no padding at all when I sit down.”

Fowler on a technical ice pitch. Photo: Victor Saunders

Fowler is sure that was his worst night in the mountains ever. But Saunders interrupted him to disagree: “Nah, I can think of worse nights, like that hanging bivouac on Spantik in 1997.”

“Oh, that was a good one too!” Fowler conceded. Here’s a pic:

A grim bivouac on Spantik, 1987. Photo: Fowler/Saunders

Terrible weather

After the terrible night sitting up, it was summit day.

“Unfortunately, it was not a very good weather,” Saunders recalls. “It was windy, cold, and misty. We couldn’t see very much. so the summit views were not as we would have liked. In fact, our summit photos could have been taken anywhere.”

No wonder they barely stayed on top for five minutes before rappelling down the ascent route. At first, they thought they’d have to do another bivy. In fact, they intended to stop at their first bivy point but missed it in the dark. The weather was so bad that they continued rappelling throughout the night, 10 or 12 hours in all, and made it all the way down.

The northwest face of Yawash Sar. Photo: Fowler/Saunders

Clear priorities

Asked about whether they have considered indulging themselves in more comfortable climbing at this stage — say, going to Manaslu instead and sipping champagne in Base Camp. No interest in that, as Saunders explained:

The kind of climbing we did on Yawash Sar means it’s just me and Mick, the cook and kitchen boy in Base Camp, and no one else. We have the whole area, the whole valley, entirely to ourselves. There is a very special place in heaven for that kind of experience. No one had ever been to that side of the mountain or that end of the valley before.

And the uncertainty is part of the adventure for us. It is exactly what we enjoy. On Manaslu, it would be exactly the opposite: hundreds of climbers, all going clipped to the same rope on a path made for them. It’s just awful — at least for me!

Next goal

They intend to keep climbing in the same style.

“However, as we grow older, we have to pick objectives that are just right for us,” Fowler explained. “These are different from what we would have done in our 30s. It has to be attainable but still steep enough to be exciting.”

Fowler on a Himalayan wall. Photo: Mick Fowler

The goal is to find climbs that include exploration.

“It has to be spectacular, not climbed, doable from the most obvious line, and if possible, on a mountain that is unclimbed or at least little visited,” said Fowler. “A route which also offers some aesthetic pleasure, and located in a culturally interesting area, and just the right amount of difficulty. We need to think: ‘We hope we can do it but we have no certainty that we can do it.’ ”

As usual, they keep quiet about future plans.

“Some people are too lazy to do their own research and copy from others’ plans, which is sad, as it does not show a lot of respect for others who have put a lot of effort planning an expedition,” said Saunders.

Saunders and Fowler’s idea, which they may scout this year, will come to fruition in 2026.

“I have to admit that it is getting more and more difficult to find objectives that are just right for us, inspiring mountains like Yawash,” Fowler said.

Changes in climbing

In nearly 50 years of Himalayan climbing, Fowler and Saunders have seen many changes in how expeditions are done. When they started, there were no agents or outfitters.

“You’d go there, find and hire a cook and porters yourself, arrange food, and so on,” said Saunders. “Now logistics are much easier since a company takes care of it for you.”

He adds: “Roads have also been pushed further and further into the mountains, sparing climbers the long walks in and allowing much shorter expeditions.”

Finally, the equipment has improved greatly. “Three times as efficient,” says Saunders, “three times lighter, three times better and safer.”

Victor Saunders on the fourth pitch on the second day on Spantik’s Golden Pillar in 1987. Photo: Mick Fowler

For Fowler, the game-changing advance was communications.

“[It went] from having to find a mailman to carry letters to a town with a post office to the satellite devices that allow communications with your family, but most of all, to call for a rescue immediately from the mountain,” he said.

Saunders argues that communications have compromised that feeling of remoteness.

“Now, for better or worse, we have forecasts, but we also may end up discussing domestic problems with the family while in the middle of the climb,” he says.

Clear priorities

Through the years, career, marriage, health, and illness, Mick Fowler’s climbs have been a continuous line adding structure to his life. Yet he wants to make his priorities clear.

Climbing is my hobby; the most important thing in my life is my family. And climbing has sometimes involved a big juggling act between family, work, and limited holiday time…Before I got married and had children, we would go climbing every weekend, and all our holidays were climbing holidays. But when I had a family, I couldn’t sensibly go climbing every weekend, and I decided to devote time to family.

Of course, climbing was also important to me, so I tried to merge climbing into my family life, and had family climbing weekends too. Then I retired, and then I got cancer. And doctors fixed me but left me with some inconveniences. But all that has not dimmed my desire to keep climbing with Victor.

Mick Fowler on Pointless, Ben Nevis. Photo: Victor Saunders

Advantages of a late start

Saunders has climbed for fun and for work. In his opinion, a late start is not a bad thing.

“I worked as an architect until age 45, then trained as a guide and qualified at 46. I only did my first Himalayan expedition when I was 30 years old, so I guess I was slightly late. That has been good for my knees, which are not that worn out. I was lucky to have had an office job before I moved to Chamonix, so I avoided injuries or excessive strain in my youth.”

None of the two veteran climbers follow a specific training or nutrition plan. But they basically keep moving.

“I don’t have a training program, but some years ago, I took up trail running,” said Fowler. “I’ve always been noticeably slow in the mountains, and friends kept asking me if I was okay. So now I have managed to speed up a bit. I do a race every other week, usually in the hills of the UK.”

Saunders, meanwhile, likes cross-training — a bit of skiing, a bit of hiking, a bit of climbing.

“I think that prevents injuries as the movements are different,” he said. “As you grow older, injuries can really stop you. They hurt more and last longer. One way to avoid it is by not focusing on a single activity.”

Victor Saunders, left, and Mick Fowler on the summit of Sersank. Photo: Mick Fowler

“We must assume the day will come when injury or age will force us off the higher peaks,” says Fowler. “Even then, I hope we can keep doing things, spending time and enjoying ourselves in the mountains.”