Last summer, Liu Yang and Song Yuancheng of China made the first ascent of Karjan I, the fourth highest unclimbed peak on Earth. The feat prompted the climbing community to wonder when — if ever — Western alpinists will again be allowed into the region to bag first ascents and new routes.

Not just the answer but even the question itself is tricky. Climbing in Tibet is not officially banned anymore, as it was during COVID. However, no procedure is simple in Tibet. The region has endless possibilities not only for exploratory alpinism but also for guided climbing and trekking. Its mountains are wild and little-visited, yet are easily accessible, thanks to excellent infrastructure.

Chinese climbers at the base of Karjian I some weeks ago. Photo: Liu Yang

After the People’s Republic of China annexed Tibet in 1951, the entire region — mainly an immense plateau defended by the Himalayan mountains on its south side — has been under the administration of the People’s Republic of China. Tibet is divided administratively into the Tibet Autonomous Region and parts of the Qinghai, Gansu, Yunnan, and Sichuan provinces.

The region borders Nepal, as Everest and Cho Oyu climbers know well, but also India, Bhutan, and Myanmar to the south; the disputed region of Kashmir to the west; the Uygur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang to the northwest, and the Chinese provinces of Qinghai to the northeast, Sichuan to the east, and Yunnan to the southeast.

Illustration: Handmade Software, Inc. Image Alchemy v1.14

History: Closed Fortress

Leaving aside Tibet’s often troubled history and focusing only on options for foreign climbing expeditions, Tibet was traditionally closed to outsiders. The few incursions by explorers were unauthorized.

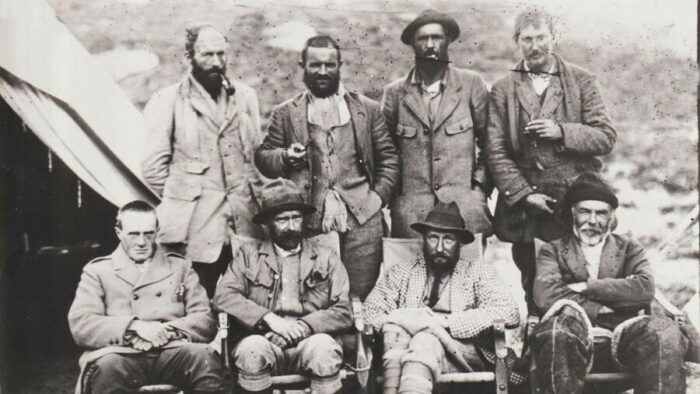

The Dalai Lama’s Tibet officially agreed to the 1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition and the subsequent expeditions of 1922 and 1924 after long negotiations between the Lama’s regime and the Indian-British government. In these years, Nepal was even more tightly closed to foreigners.

Members of the 1921 Everest expedition, with leader Charles Howard-Bury (seated second from right). Photo: Marian Keaney

After the Chinese annexation, the territory was only re-opened to foreign climbers after former premier Deng Xiao Ping’s open-door policy began in 1980, according to Tibet explorer Tamotsu Nakamura. He has led over 30 expeditions to Tibet.

By the turn of the millennium, optimism about future opportunities was high.

“Access is opening even further under the West China Development Plan, which is reaching the most isolated frontiers,” Nakamura wrote in 2003. “Even the least-frequented rural areas are experiencing rapid changes.”

Yet access for mountaineers has always required elaborate red tape, several permits, and considerable cost, including unexpected charges once in Tibet. And things did not improve over time.

Unknown 6,000’ers in Eastern Tibet by Jamb Tso Lake. Photo: Tamotsu Nakamura

Increasing hassle

In 2013, Mark Jenkins described the situation in a piece about potential first ascents in Tibet in Backpacker Magazine.

“In 2012, independent travel within Tibet’s official boundaries became even harder,” he wrote. “Only group tours and parties of five or more were allowed at press time, and all individuals in a private party had to be of the same nationality. No thanks.”

At that time, Jenkins and his climbing partner decided to forgo Tibet and headed instead for peaks in Sichuan province, where “anything below 6,000 meters doesn’t require a permit.”

During that decade, bureaucratic hassle deterred more and more climbers. At the same time, more peaks and areas opened in Pakistan and Nepal. In Nepal, the mountain tourism industry flourished with more operators, local services, and the increasing use of helicopters.

The ‘golden’ 8,000’ers

The exception to limited access to Tibet was the three 8,000’ers: Everest from the North Col and the Northwest Ridge, Cho Oyu (whose normal route lies in Tibet), and Shisha Pangma, located entirely within Tibetan territory.

The management of permits and expeditions earned hefty amounts for the China Tibet Mountaineering Association, and the peaks were open most years. However, restrictions have kept increasing, with climbers needing to adjust to sudden changes in climbing periods, regulations, and prices.

Tents at the base of Shisha Pangma. Photo: Seven Summit Treks

A handful of badass climbers risked sneaking into Tibet, either to climb Cho Oyu or nearby peaks by crossing from Nepal at the Nangpa La Pass. That remains a serious breach of law, and the consequences could be serious if caught by Chinese authorities.

Some climbers managed to get all their visas and permits and entered Tibet legally until 2019. For instance, Explorersweb covered a trip by American Luke Smithwick to 7,250m Labuche Kang III East in 2018. In 2019, Nirmal Purja and a small Sherpa team obtained a special permit to climb Shisha Pangma in order to complete his Project Possible.

Before and after COVID

A more serious closure came at the beginning of 2020, prompted by the COVID pandemic.

Since then, as the pandemic eased, most climbing teams have applied only for the bigger peaks, especially since the high-altitude industry thrives on ambitious climbers pursuing the 14 8,000’ers. Everest climbers also come to avoid the crowds on the South Side and the hazard of the Khumbu Icefall.

The first permits were finally granted in the fall of 2023 for Cho Oyu and Shisha Pangma, but the tragic deaths of two female climbers and their guides in an avalanche on Shisha Pangma prompted the CTMA to swiftly close the peak, not just for the rest of that season but for the spring of 2024 too.

Climbers and climbing sherpas head up from the North Col towards Camp 2. Photo: Jamie McGuinness

Only four Nepalese companies received a limited number of permits in fall, under a strict set of rules. Surprisingly, some climbers then happily ignored one of these rules, which banned climbs without supplemental oxygen. A number of sherpa guides and Western climbers blithely announced that they summited Shisha Pangma without bottled gas.

The North Side of Everest finally reopened this past spring to one Nepalese and three Western companies. Here, the rules were strictly followed, and no one climbed without oxygen.

The situation remains more frustrating for alpine-style teams focused on new routes and first ascents. We have not heard of any such team granted a permit or even trying to apply for one. Thus, news of Chinese nationals bagging one of the highest unclimbed peaks in the world causes some grumbling and resentment among those who wish they had the chance to attempt such a tantalizing goal.

Chinese climbers at the base of Karjian I some weeks ago. Photo: Liu Yang

Foreigners in Tibet: how and where

Officially, foreigners are allowed into Tibet as long as they have a visa. Trekking groups outfitted by a Tibetan operator and accompanied by local guides are also permitted to hike up peaks below 6,000m. Since the COVID restrictions eased, local outfitters have been eager to promote international tourism in Tibet.

There is also a list of 6,000m and 7,000m peaks open to both local and foreign expeditions. These must still acquire climbing permits and fulfill all the requirements of the CTMA. While the exact fees for all these peaks are unclear, they are believed to be quite pricey.

The list of open peaks in 2024 included: Milan Peak (6,100m). Guring La trek/Mt. Kaluxung (6,674m), Kalurong (6,674m), Mt. Pulha Ri (6,404m), Chomo Kara (6,140m), Mt. Chitzi (6,206m), Mt. Jansung Lhamo (6,325m), Nyenchen Tanglha (7,162m), and Kula Kangri (7,538m).

Mt. Kaluxun (or Kalurong) in Tibet. Photo: Wikipedia

There are more, but the authorities remain conservative and not transparent about their process. As far as we’ve been able to determine through Chinese contacts, the CTMA does not even have a website. Local outfitters act as intermediaries.

Basically, you file your application, try to dot all the i’s, and keep your fingers crossed. Yes or no does not come in a timely fashion, so you are not sure whether to buy your plane tickets or not.

Two guides told ExplorersWeb that an updated list of peaks open in 2025 may eventually come. Right now, one said, only the 8,000’ers and Lakpa Ri, a 7,043m peak close to Everest, are confirmed open for next year.

Higher sections on the North Side of Everest, with Lakpa Ri in the background. Photo: Alpenglow Expeditions

Careful scrutiny

While the 8,000’ers remain the most coveted summits in Tibet, other once-popular peaks have seen a sharp decrease in visitors or are no longer accessible.

Anyone hoping to get a visa to enter Tibet and a climbing permit will be carefully scrutinized. Recently, two famous climbers from a top-level expedition to Everest were refused entry visas. Although the CTMA and local operators profit from foreign climbers, China has such a huge domestic market that it does not need that relatively minor source of income. Any criticism of China in one’s online personal history might prompt the denial of a visa or permit.

The best approach is to contact an outfitter about paperwork, China visas, Tibet travel permits, climbing options, etc.

Here is info about the different permits and visas required.