Mountains with year-round ice caps gain height from a permanent layer of snow and ice. Traditionally, there were five of these ice-capped peaks in the contiguous United States, and the most famous of them is Mt. Rainier.

But climate change is coming for these peaks. A new study in the journal Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research shows that all five have lost height due to ice melting.

Mt. Rainier, photographed by Alvin H. Waite in August, 1895. Photo: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections

High-altitude science

People who visit the mountains every year notice melting ice, newly exposed rock, more rain, and less snow. But collecting precise data at the summit of a mountain requires one to actually reach the summit with delicate instruments intact, and that is a specialized skill set.

In late August 2024, a team funded by the American Alpine Club surveyed the Lower 48’s five ice-capped peaks, led by experienced mountaineer and researcher Eric Gilbertson.

At the summit, they conducted ground surveys using GNSS equipment (Global Navigation Satellite System) on loan from Seattle University. Here, researchers use several GNSS devices, including one with a known position, to get a more accurate reading. For this, the team had to spend several hours on each summit.

Once they had the 2024 measurements, researchers compared them with past data gathered by LiDAR, photographic analysis, and earlier theodolite surveys.

Eric Gilbertson on Mt. Rainier’s Liberty Cap, September of 2024. Photo: Ross Wallette

A changing landscape

The results were troubling, to put it mildly. In 1956, Mt. Rainier measured 4,392.2m (14,410′) at its highest point, Columbia Crest. As of 2007, however, Columbia Crest is no longer the summit of Rainier. That honor now goes to a 4,389m (14,399.6′) rocky outcrop about a football field away. Columbia Crest, meanwhile, continues to melt, measuring only 4,385.8m (14,390′) at the time of the study.

“All told,” the study announced, “Mount Rainier is no longer an ice-capped summit.” Average temperatures at Rainier’s summit have risen over 3˚C since the 1950s, causing this drastic change.

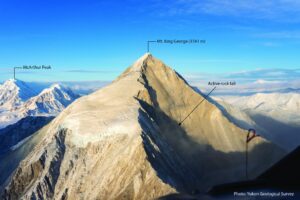

As for the four other peaks, only two of them remain ice-capped. Liberty Cap, a sub-peak of Mt Rainier, and Colfax Peak, a sub-peak on Mt Baker, have a few remaining meters of ice. El Dorado Peak and East Fury have both lost their caps, and with them, several meters of elevation.

The majority of this ice loss has occurred since 1999. Not only are Washington’s frozen peaks losing ground, they are doing so at an increasing rate. East Fury, on Mt. Fury, is both the lowest peak and the one losing ice most rapidly, which seems unfair. The study notes that the data on trends over time is preliminary.

However, it does show the ongoing danger that climate change presents for alpinists. There will be increasing confusion and debates about records, as summit locations and elevations change from year to year.

But it’s also a reminder of the importance of mountaineering in climate research. Even with advanced satellite and remote sensing, on-the-ground survey work is key to understanding and measuring how our mountains are changing.