So far, the three High Arctic deaths we’ve covered in this series have all been the certain result of foul play. Charles Francis Hall’s death is more mysterious. It may have been a murder whose motive combined expedition friction and a love triangle. Or maybe not.

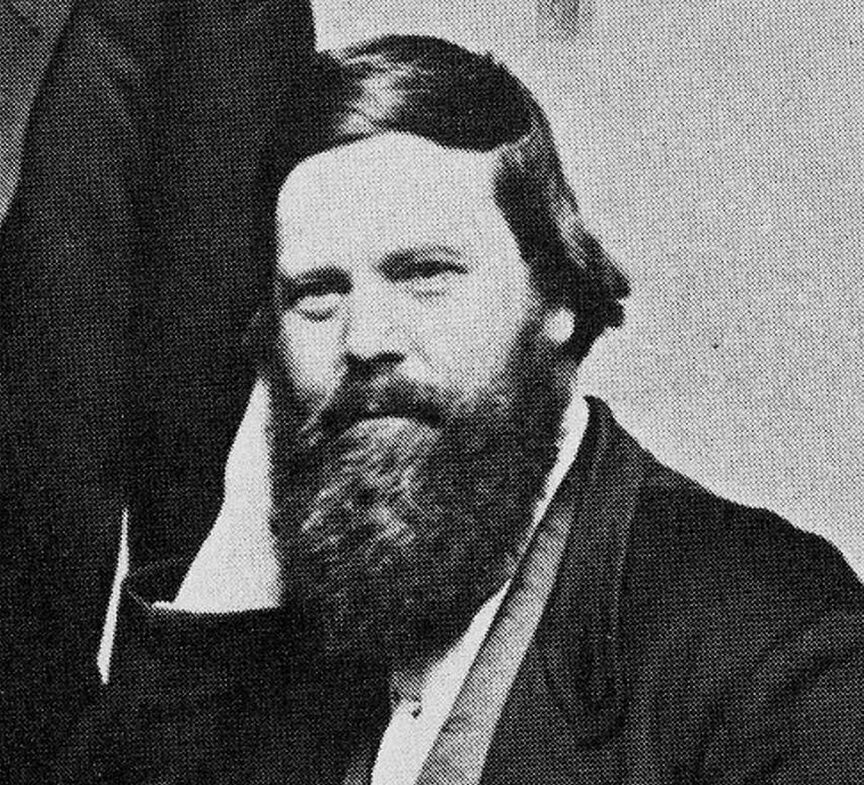

Hall’s background as an arctic explorer was unusual. He grew up in New Hampshire with little education, became an apprentice blacksmith in his teens before moving to Cincinnati. Here, he somehow became a businessman and newspaper publisher. He only became interested in the Arctic in his late 30s, drawn in like many others by the mystery of what happened to John Franklin and his crew.

In 1860, at the age of 39, Hall went north for the first time as a passenger on a whaling ship. Although they didn’t reach the area where Franklin disappeared, Hall turned the voyage into an exploration. They showed that “Frobisher Strait” on southern Baffin Island was really just a bay and brought back some artifacts from Frobisher’s expedition.

A remarkable couple

He also met a remarkable Inuit couple who spoke English, Ipirvik and Taqulittuq. Historically known as Joe and Hannah, they became prominent guides for several white explorers and accompanied Hall on all three of his expeditions.

His second expedition began in 1864. This time, he reached King William Island in the central High Arctic, where Franklin’s ships became trapped in the ice and where so many men perished. He made no great discoveries but did find some bones and other remains from the lost expedition.

Hall stayed north for several years, learning from Inuit like Ipirvik and Taqulittuq how to live in the Arctic. Unlike many famous explorers who went north merely as a career move, Hall genuinely loved the place.

“The Arctic is my home,” he wrote once. “I love it dearly; its storms, its winds, its glaciers, its icebergs; and when I am there among them, it seems as if I were in an earthly heaven or a heavenly earth.”

Hall’s attraction to the Arctic and curiosity to learn made him an excellent independent traveler. He was also undoubtedly a good self-promoter. He came out of nowhere, and through interest, vigor, and self-marketing, turned himself into one of the foremost American arctic explorers of his time.

Not a leader

But as a leader of men, he was poor at commanding loyalty. In 1868, still on that second expedition, he shot and killed a crew member under questionable circumstances. Hall later claimed the man was attempting mutiny, but other whalers on the ship said the murder was more frivolous. Nevertheless, Hall was never prosecuted.

On his return to the United States, the former blacksmith’s apprentice found himself in lofty circles. U.S. President Ulysses Grant and members of Congress secured for Hall a $50,000 grant — about $1.3 million in today’s dollars — to lead an expedition to the North Pole. In 1871, Hall, an old whaling captain named Sidney Budington, who also captained the whaler on Hall’s first expedition, and many others set out for North West Greenland aboard a ship called the Polaris.

The Polaris. Painting: William Bradford

The expedition featured even more drama and conflict than usual. Hall was the leader but was not the ship’s captain. Some of the crew — particularly a troublesome German contingent — resented his authority. Factions on the ship made the atmosphere tense.

Nevertheless, it was a good ice year — one of several in the last quarter of the 19th century — and the Polaris forged north between Canada and Greenland as far north as 82˚11′, the highest latitude a ship had ever reached. There, pack ice forced them to retreat about 50km to 81˚37′ on the Greenland side. They found refuge for the winter in a sheltered nook called Thank God Harbor.

Greenland, background, lies 30km across broken pack ice from northern Ellesmere Island, where this picture was taken. Thank God Harbor, where the Polaris overwintered, is just to the right. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

A mysterious death

In October — by which time the sun had already set for the winter at that latitude — Hall dogsledded north for two weeks on a brief exploratory mission toward the North Pole. When he returned, he became violently ill after drinking a cup of coffee. The ship’s doctor, Emil Bessels, diagnosed apoplexy — a stroke.

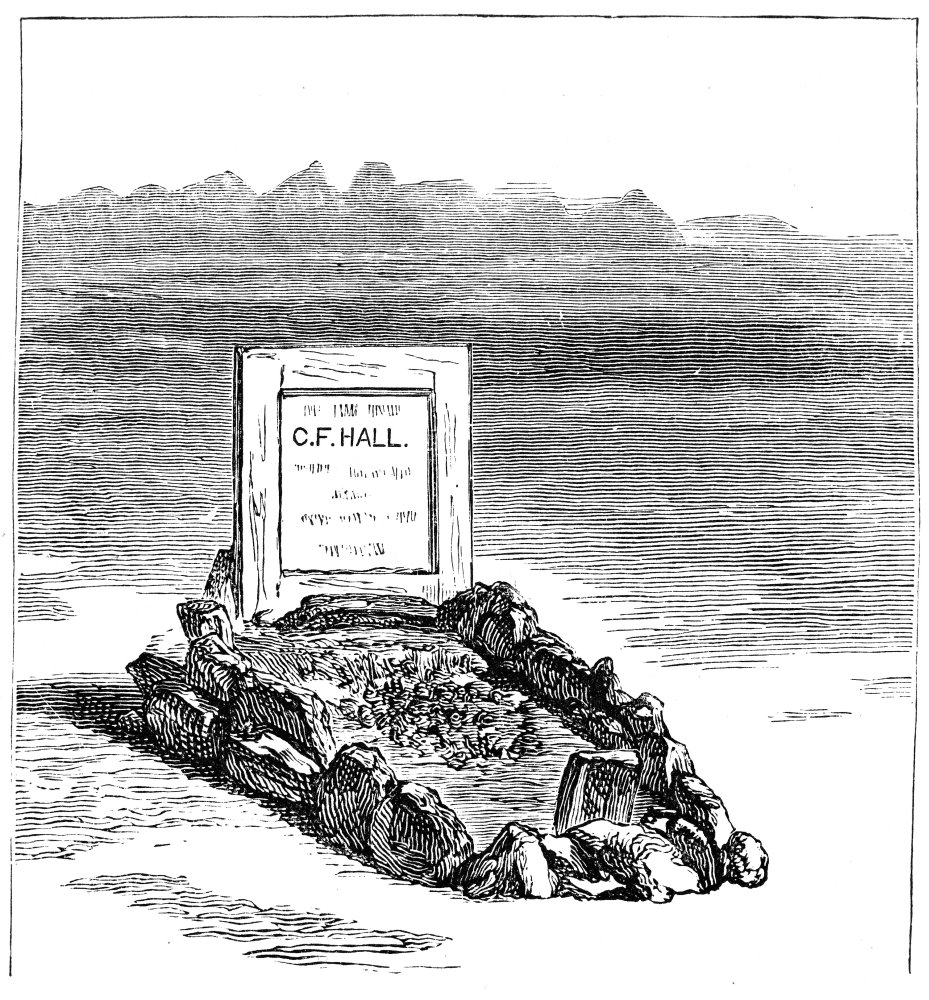

Bessels and Hall had quarreled in the past. Confined to his cabin, Hall accused the doctor of trying to poison him. Hall had also fallen out with his old whaling captain pal, Budington. Nevertheless, the vomiting and delirium abated, and Hall seemed to be improving. But then on November 8, he died. They buried him in the tundra in Thank God Harbor.

An artist’s rendition of Hall’s funeral procession. Photo: Wikimedia

Hall’s grave.

Hall’s grave today.

The drama was far from over for the crew of the Polaris. The following summer, Budington managed to sail the damaged vessel south about 300km to near Etah, a temporary hunting community that later served as the base for several white explorers.

Morale continued low. Then the ship was caught in the pack ice and was in danger of being crushed. There was a call to abandon ship, and 19 of the crew took refuge on the ice, along with some supplies that had been hastily thrown overboard. At that point, the damaged ship unexpectedly broke free of the pack and drifted off, leaving the 19 behind. We wrote about their ordeal, perhaps the most miraculous survival in arctic exploration, in a previous article.

The Polaris itself was eventually shipwrecked near shore, but the crew remaining on board survived the winter. Then, the following summer, they sailed their small boats south, where a whaling ship picked them up.

Detective work

But what had happened to Charles Francis Hall? The mystery persisted until 1968, when writer Chauncey Loomis went to Thank God Harbor and exhumed Hall’s body. The dry cold had preserved it for over a century. They took samples of his bones, fingernails, and hair, then reburied the body. Back south, they analyzed the samples and discovered that Hall had died not from a stroke but from large amounts of arsenic consumed during the last weeks of his life.

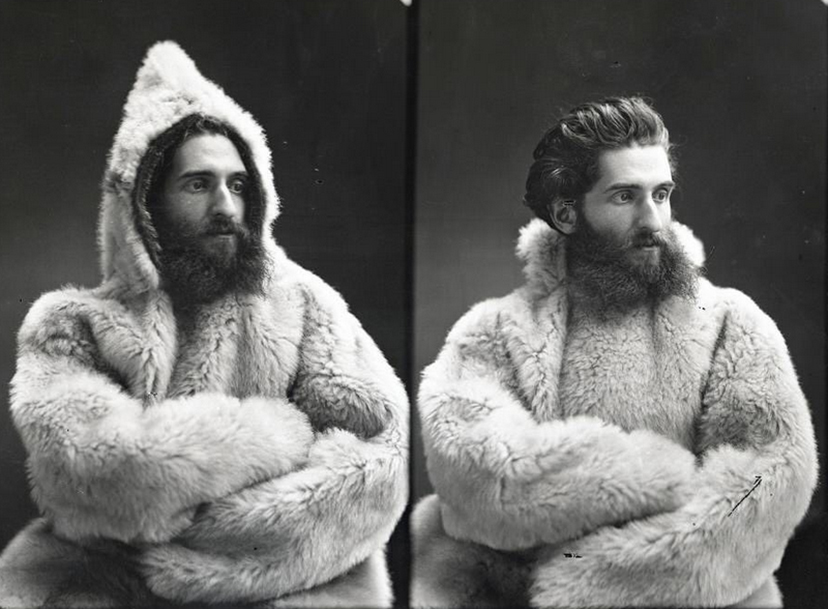

Arsenic was a component of the ship’s medical kit, as it featured in many quack medicines of the day. Suspicion fell on the doctor, Emil Bessels. “If Hall was murdered, Emil Bessels is the prime suspect,” Loomis later concluded in his fascinating book Weird and Tragic Shores.

However, Hall also had his own medical kit and might have accidentally self-administered the arsenic through some patent medicine.

Emil Bessels. Photo: Smithsonian Institution

We’ll never know whether Hall was murdered or died unwittingly by his own hand. But in recent years, arctic scholar Russell Potter found an intriguing connection between Hall and Bessels that may have given the German doctor a motive other than personal dislike.

Vinnie Ream

Before sailing on the Polaris, Hall and Bessels both made the acquaintance of a beautiful young sculptor named Vinnie Ream. Ream “was attracted by [Hall’s] bear-like quality…but Bessels became instantly infatuated with her,” according to a source cited by Potter. Both Hall and Bessels later wrote to Reams. Could this have spurred the doctor to rid himself of a romantic rival?

Vinnie Ream. Photo: Wikipedia

Other articles in this series:

Murder Near the North Pole, Part I: The Death of Ross Marvin

Murder Near the North Pole, Part II: Death on an Ice Island

Murder Near the North Pole, Part III: The Death of Peeawahto