In 1909, a young American, Ross Marvin, was helping Robert Peary on his last North Pole expedition. Marvin did not survive. He supposedly fell through a crack in the sea ice and drowned. Years later, it came to light that his death was no accident.

While part of the joy of expeditions is the deep bond that can form between partners, the chemistry doesn’t always go well. Arctic exploration, in particular, can be so stressful that several murders and near-murders have occurred. Henry Hudson and his son were set adrift in a lifeboat by a mutinous crew and never seen again. Elisha Kent Kane almost killed one of his troublesome men by bashing his skull with a belaying pin. Charles Francis Hall was likely poisoned with arsenic by his ship’s doctor. On an American expedition in 1914, a privileged young man named Fitzhugh Green panicked in a storm and shot his Inuit companion Peeawahto, thinking Peeawahto was abandoning him.

The grave of Robert Janes at Pond Inlet on Baffin Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Erratic behavior

The Inuit sometimes killed people too, including white visitors. Occasionally, white men behaved so erratically that the Inuit considered them dangerous. That was the case with the overbearing trader Robert Janes on Baffin Island. His 1920 murder led to the first case in which an Inuit man was prosecuted under white man’s law.

And then there was the curious case of Ross Marvin.

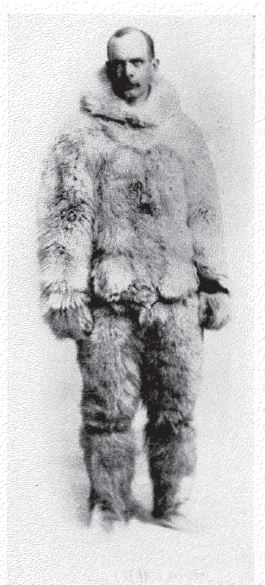

Ross Marvin.

Ross Marvin was a Cornell University graduate who had accompanied Peary once before, in 1905-6. On the ship, Marvin served as the aging explorer’s secretary. But in 1909, he headed a four-person team composed of himself and three Greenlanders — Kudlooktoo (Qilluttooq in modern orthography), his cousin Inukitsoq, and Aqioq. Their job was to shuttle loads forward over the Arctic Ocean so that Peary, at the apex of this pyramidal system, could advance quickly with a light sled toward the North Pole.

Kudlooktoo, red arrow, on an earlier Peary expedition.

Marvin’s personality

Accounts of Marvin’s personality — which is relevant to this story — differ widely. Peary’s longtime manservant Matthew Henson described Marvin as “a very quiet young man, but one of great courage and strength of character…cool-headed, quiet, and just.”

Peary, a difficult man whose word must always be taken with a grain of salt, was also complimentary: “Quiet in manner, wiry in build, clear of eye…[Marvin’s] good humor, his quiet directness, and his physical competence gained him at once [the Eskimos’] friendship and respect. From the very first, he was able to manage these odd people with uncommon success.”

Others, however, described Marvin as someone who never laughed, even “a pain.” Inukitsoq claims Marvin threw a tantrum after Inukitsoq had followed Kudlooktoo, not Marvin, around a lead — an open water crack in the sea ice.

“Suddenly, we became afraid of him,” Inukitsoq reported years later.

Marvin, lying down in furs and protected from the wind by snow blocks, takes a navigational reading en route to the North Pole.

Polar controversy

Marvin accompanied his commander as far as 86˚38′ north before Peary sent him back to land. It is unclear how much further Peary got, but modern historians accept that while Peary claimed he reached the Pole on April 6, he fell significantly short, and he knew it. He had sent back not only Marvin but all the white companions who could verify his navigation. He kept only Henson and two Inuit with him.

Ross Marvin.

Meanwhile, Marvin and his small party struggled to return to northern Ellesmere Island. They crossed dangerous patches of thin ice; twice, Marvin fell in the water and was rescued by his companions. On the third occasion, the Inuit later reported, Marvin drowned.

Marvin’s memorial, past and present. Left: Robert Peary. Right: Jerry Kobalenko

After Peary returned to the ship in late April, he learned of Marvin’s death. He had a cairn built for the young man, topped by a cross with a memorial plaque. The cross and plaque toppled from the cairn but still lean against it at Cape Sheridan today. The plaque’s wording, neatly done in stippled lettering with a hammer and some kind of metal point, states: “In memory of Ross G. Marvin, Cornell University, aged 31. Drowned April 10, 45 miles N of Cape Columbia, returning from 86° 38’ N. Lat.” (Marvin was actually 29.)

Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Aftermath

When Peary returned to civilization, he notified Marvin’s parents by telegram of their son’s death. In typical Peary style, he sent the telegram collect.

By then, he was embroiled in something much more important to him: He had to discredit Frederick Cook, who said he himself reached the North Pole a year earlier — a claim now also recognized as false. And Peary had to defend his own claim. Despite several glaring holes in his account, Peary eventually won the battle. He was almost universally recognized as the “discoverer” of the North Pole until the 1960s when the doubts began to resurface.

Fourteen years after that North Pole expedition, in 1923, Kudlooktoo converted to Christianity and was baptized. He wanted to clear his conscience and confessed that the story of Marvin drowning in a lead was false.

“After my baptism, I did not want to keep this murder secret,” Kudlooktoo stated.

It turns out he had shot Marvin in the back of the head, pushed him into the water, and then concocted the drowning story with his two Inuit companions.

What happened on the ice

What happened was this: On their way back from their Farthest North, a stressed and frostbitten Marvin behaved impatiently. He forced the party to cross stretches of thin ice rather than wait for it to freeze more thickly, as the Inuit advised. When young Inukitsoq fell sick, Marvin ordered the others to abandon him.

As mentioned above, it had happened before in the Arctic that when white explorers behaved in a way that the Inuit considered a danger to themselves, execution was regarded as a rational solution. Kudlooktoo shot Marvin in order to save Inukitsoq.

In 1925, the Greenland explorer and ethnologist Knud Rasmussen heard the story of Kudlooktoo’s confession and spoke to Kudlooktoo to verify the details. Rasmussen then reported it to the Danish government and brought the news to the United States.

In 1926, there was pressure to extradite Kudlooktoo to the U.S. to face charges. But Denmark then suggested that in that case, they would ask that Fitzhugh Green be extradited to Greenland to stand trial for the murder of Peeawahto in 1914.

In the end, neither man was ever charged.

Peeawahto shortly before his murder.