Last week’s rescue of Azif Bhatti by Israfil Ashurli on Nanga Parbat ended happily for both Bhatti and Ashurli, sort of. Both are frostbitten and in the hospital, Ashurli told ExplorersWeb today.

Pawel Kopec was not so lucky. He died helpless, barely 200 meters away from a tent. Worst of all, he might be still alive if some other climbers had shown the generosity that Ashurli and partners Saulius Damulevicius of Lithuania and Volodymyr Lanko of Ukraine displayed toward Bhatti.

Climbers point fingers

“I have a lot to say about starting the summit push from C3 [and] not helping climbers 200m away,” Damulevicius told ExplorersWeb from Chilas, a city in Gilgit-Baltistan.

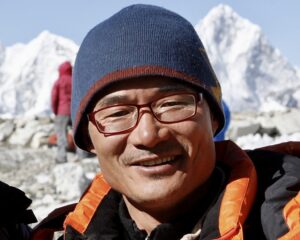

Saulius Damulevicius. Photo: Saulius Damulevicius/Facebook

We also spoke with Flor Cuenca of Peru. Although she passes almost unnoticed, Cuenca is one of the most interesting figures around 8,000m peaks these days. On July 2, she summited Nanga Parbat from Camp 3. It was her 8th 8,000’er without oxygen or sherpa support.

In both directions, she passed others, climbing with and without oxygen. “Either I was very well acclimatized, or people were shockingly slow,” she said.

As she reached Camp 3, she left behind the drama unfolding above her. But in an interview with ExplorersWeb, she gave valuable information about what she saw that day and the day before.

Too long from Camp 3 for no-O2 climbers

Cuenca was strong enough to manage the push from Camp 3 and back again. But for most of those heading to the summit of Nanga Parbat without O2, skipping Camp 4 was a serious mistake, Damulevicius pointed out.

This year, commercial teams didn’t try to set up a fourth camp, which typically lies around 7,400m. Instead, they launched their summit pushes from Camp 3 at 6,800m. This might be okay for many climbers on supplementary O2, but it is a long haul for those without extra gas — and there were a number of them. Damulevicius, Ashurli, and the Italian team led by Mario Vielmo were the only ones who pitched tents at Camp 4.

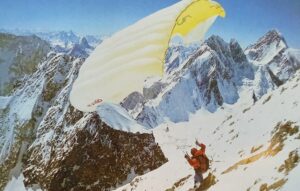

Lanko at 7,150m, on his way to Camp 4. Photo: Saulius Damulevicius

The Lithuanian remarks that they acclimatized well and set up camp at 7,350m. He believes that they would have summited if their tent had not become a de facto first-aid station for climbers coming from down the summit in a poor state.

Cuenca confirms that most of those who summited without oxygen were in trouble on the way down. She noted that the Lithuanian-Ukrainian-Azerbaijani team helped these too-ambitious climbers at the cost of their own attempt. The weather became stormy after they got into the tent. Damulevicius recalls what happened next:

Almost at the same time, the radio station starts shouting ominous messages from the base [BC]: “Valdi [Waldemar Kowalewski] is no longer oriented, he needs help descending,” “Pawel [Kopec] has altitude sickness, he no longer knows his name,” “Mariusz [Szczechowicz ] is delirious from hallucinations,” “Csaba [Varga, from Hungary] is frozen, lost gloves,” “…a lot of frostbite”… [Damulevicius also radioed for someone to bring oxygen for a climber in trouble near Camp 4. It never arrived.]

Soon, frozen climbers begin to pour into the vestibule of our tent. A raging blizzard fills the tent with snow. We serve everyone tea and try to get a handle on the situation by asking for information. Around midnight, we already understand that it was not Valdi [Kowalewski], but Csaba who needed help going down, and that Pawel is probably still in the greatest danger. Around one o’clock in the morning, when we were supposed to leave for the summit (a long-forgotten plan), we hear Valdi near the tent. He announces that Pawel, who is already near C4, needs help. Then he continues the descent to C3.

Give advice or mind your own business?

Cuenca saw Mariusz Szczechowicz on her way down from the summit. He was sitting in the snow. She asked how was he doing. He looked normal but strangely, he asked Cuenca if she was doing an acclimatization rotation. She thought at first that she had misunderstood him, but looking back now, the Polish climber might have been already hallucinating.

“I have always believed that everyone on the mountain knows how they feel and what they have to do,” Cuenca said. “I am not keen on giving advice if not asked. But perhaps I have been wrong all this time.”

Cuenca also crossed paths with Asif Bhatti, well below Camp 4. “He was extremely slow, extremely late, and definitely not doing well,” she recalled. “I should have told him to stop and turn around.”

Flor Cuenca on Nanga Parbat, below the Kinshoffer Wall. Photo: Flor Cuenca/Instagram

Finally, Cuenca also saw Santiago Quintero of Ecuador. He had turned around at some point and was slowly descending. Cuenca continued to a relatively sheltered spot, where the wind was not so strong, and waited for him for about half an hour.

“Then my fingers started aching from the cold,” she said. “I was tired, and with frostbite beginning, I started moving again until I reached Camp 3. There, I drank a cola and got into the sleeping bag.”

Porter left outside at 6,800m

Cuenca let two people use her tent. One was fellow Peruvian Victor Rimac. The other one was a high-altitude porter whom she found abandoned outside the previous night.

His name was Akhbar. On July 1, people started preparing for the summit push in Camp 3 from 5 pm. Some had trouble finding their tents, which had been covered in fresh snow. I saw this guy by the door of a tent, then walking up and down, then standing in front of another tent… Eventually, I asked him. Shivering, he said he was waiting for his clients to leave the tent [on their summit push] because, he said, there was no room for him.

It was already 7:30 pm. He had no high-altitude gear. My tent was small and Victor was already inside, but I told him to get inside and use my fuel [to melt water]. I was shocked and angry. Treating local climbers like animals is unacceptable, it makes me so furious!

Tents in Camp 3 on Nanga Parbat after a snowy night. Photo: Saulius Damulevicius

The porter told Cuenca that he was working for Juan Pablo Toro of Argentina and Valerio Annovazzi of Italy (teammates of Mario Vielmo, Nicola Bonaiti, and Tarcisio Bello). We asked Juan Pablo Toro for comments but have not heard back by the time of posting.

Victor Rimac finally gave up his summit attempt because of health reasons and returned to Base Camp. He is now on his way to the Gasherbrums.

Kowalewski’s take on the story

As for Waldemar Kowalewski, in a report posted on social media, he confirms that he set off without oxygen from Camp 3 toward the summit at midnight. He reached the top at 5:20 pm and returned to his tent in Camp 3 at 3:30 am on July 3.

About the descent, he only notes he “towed” Pawel Kopec for five hours over a short section above Camp 4 and that, unfortunately, Kopec finally couldn’t make it.

In the video below, Kowalewski recorded his encounter with other Polish climbers [Szczechowicz and Kopec?]. They were on their way down from the summit (having reached the top at around 3:00 pm) while he was still going up.

Interestingly, most summiters posted about their success, but none mentioned that they were in trouble and got help — mainly with hot tea and shelter — from those with a tent in Camp 4.

Damulevicius noted that Csaba Varga of Hungary, Anja Blacha of Germany, Israfil Ashurli of Azerbaijan, and members of the Polish team were in their tent at some point in the night. He also mentioned that an abnormally high number of summiters suffered from frostbite (degree unknown), even those on supplementary O2.

The longest night in Camp 4

When they heard Kowalewski’s call for help, first Lanko and then Damulevicius went out of their tent and tried to help Pawel Kopec. He was at 7,400m, some 200 meters away from the tent, looking bad. They tried to help him to his feet but his legs “didn’t work.”

Damulevicius went to look for help. On the way, he found a “puzzled” Mariusz Szczechowicz trying to dig a platform for a tent. He took him to Ashurli’s tent nearby, where he would be taken care of. Then he went to the other tent, “occupied by three experienced climbers from Italy, one Argentinian, and a Pakistani HAP,”* Damulevicius said.

He told them he needed physical help dragging Kopec. Then he went to his own tent to gather items to tow the sick climber (a rope, a mat, and a Thermos with hot water from Ashurli). It took him some 40 minutes to get back to Volodymyr and Kopec.

*Note: The Italian-Argentinean team comprised Mario Vielmo, Nicola Bonaiti, Tarcisio Bello, Valerio Annovazzi, and Argentinean Juan Pablo Toro. It is unclear who was the HAP (High Altitude Porter) but it was not Akhbar, whom Flor Cuenca met in Camp 3 the previous day.

Cuenca said that the HAP who was with the Italians in Camp 4 was not supposed to attempt the summit either, but for some reason, he finally did. “He went up, summited, and descended — and he didn’t have a down suit!” Cuenca said. “He returned to Base Camp all right, but I told him he had been a fool.”

No one came as Pawel Kopec died

Damulevicius wrote:

Pawel is lying peacefully in the arms of Volodymyr [Lanko], who is sitting next to him. Both are breathing normally. I pour Pavel a cup of hot water. Volodymyr asks if he wants more, and with his approval, he pours another half cup. We constantly talk to Pavel, encouraging him and telling him that it is necessary to reach the tent.

Realizing that we may not get any help, we try to lift Pavel again and pull him down. Volodymyr and I immediately look at each other, because we both sense at the same time that something is wrong. Pavel is not breathing. We try to shake him and revive him, but in vain. Pawel Kopec died in my arms on July 3 at 3:19 am. Assistance from C4 and the requested oxygen cylinder from C3 never arrived.

The late Pawel Kopec in Base Camp. Photo: Saulius Damulevicius

An exhausted Damulevicius headed back to his tent after five hours of trying to help others. “Before I fell asleep, I heard the guys in the other tent prepare and leave for the summit,” he wrote on Facebook.

The Italian-Argentinian team summited on July 3 but separated on the descent. Mario Vielmo and Nicola Bonaiti made it back to Base Camp, Valerio Annovazzi and Juan Pablo Toro stopped for the night in Camp 3, and Tarcisio Bello waited for them in Camp 2. Finally, all made it safely back to Base Camp. We have asked Mario Vielmo for his take on what happened, and we are awaiting an answer.

We have also asked the leader of the Polish team, Piotr Krzyzowski, for comments about the Polish climbers’ final push, the events leading to Pawel Kopec’s death, and the failed attempts to get help from teams who were at Camp 3 at the time. It is unclear if he will be able to answer our questions any time soon. Today at 4 am, he left Skardu for the Baltoro, on his way to the Gasherbrums.

Israfil Ashurli will also provide some comments about the events shortly.

Some reflection needed

Overall, the high-altitude climbing community needs to reflect on how to prevent avoidable deaths. This includes:

- a sensible assessment of one’s skills, strength, and experience before (and while) tackling ambitious goals.

- actual protocols in case of problems, rather than leaving it all to the luck of finding climbers like Ashurli, Damulevicius, and Lanko, ready to sacrifice their dreams and even their safety in order to help.

Not all climbers act like they did. In these times of industrialized climbing, individualism, and crowded base camps where climbers don’t know each other, it may be necessary to review the (maybe old-fashioned?) values of mountaineering and the overall moral duty to help fellow humans in need. Bright social media posts can’t hide the darkness of a fellow climber dying on the snow some meters away.