A new Tourism Bill passed Nepal’s National Assembly last week. It will require climbers to have previously climbed a 7,000’er in Nepal before tackling Everest. In part, the move will prevent inexperienced or unfit climbers on the mountain, but it also boosts the country’s thriving expedition business.

Every year, new regulations are proposed for trekking and mountaineering in Nepal. We then wait to see which ones are actually implemented, and how. The difference this time is that the Everest rules are on the verge of becoming national law. This differs significantly from the regulations of the Department of Tourism or regional authorities.

The Nepali side of Everest Base Camp in 2025. Photo: Furtenbach Adventures

This Integrated Tourism Bill contains numerous rules and requirements for high-altitude climbers, especially Everest clients. Everest is by far the largest source of revenue for the expedition industry. The measures will reportedly enhance safety and protect the environment, though they will mean foreign clients will pay more. The bill passed unanimously.

7,000m before Everest

The most notable regulation regards previous climbing experience for Everest climbers. Every would-be Everest summiter must have climbed a 7,000m peak in Nepal.

File image of climbers on Baruntse’s upper slopes. Photo: Asian Trekking

“Officials say this provision is intended to curb the growing number of inexperienced climbers attempting the world’s highest peak, a trend often blamed for congestion, accidents, and strain on rescue services,” local media reported. It also explains the recent trend among Nepalese outfitters to offer expeditions to the country’s 7,000’ers, such as Himlung and Baruntse.

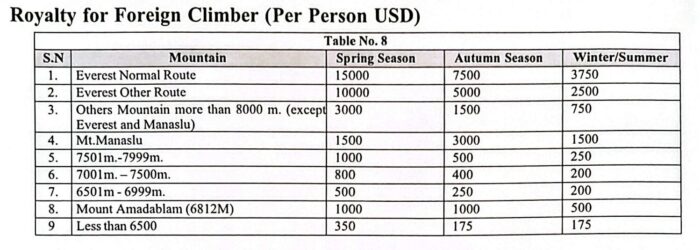

Climbing royalties for foreign climbers (in US dollars) in Nepal, updated to 2026. Source: Nepal’s Department of Tourism

There are 86 peaks (including sub-peaks) between 7,000m and 7,999m in Nepal, and the royalties for foreigners to climb them in spring range from $500 to $800, depending on the altitude. Prices drop 50% in the fall.

Several other countries in the world have 7,000m peaks (eg. the ‘Stans), but the new rule ensures the revenues remain in the country. Even if you opened a new route on K2 and won a Piolet d’Or for it, you still need a Nepal 7,000’er on your resumé before attempting Everest.

Carlonine Ogle, General Manager at Adventure Consultants, confirms the regulations may affect their potential clients in the following video:

Health and style

Some of the rules in the bill also appeared in other recent regulations, such as the requirement to submit a recent health certificate to obtain a climbing permit. The measure is common for international expedition outfitters (and the climbers themselves, for their own sake). However, the requirements now extend to the local staff, including supporting Sherpas, guides, and even the Liaison Officer.

On the upper sections of Everest, Makalu in the background. Photo: Nani Stahringer/CT7S

The permit application must also include a detailed climbing plan, specifying the route and style — meaning that there should be no surprise no-oxygen claims after returning to Base Camp or new variation routes opened on the fly. We don’t know whether applicants may report a preliminary plan, such as a no-O2 or fast ascent, “depending on conditions.” It is rather common for climbers to declare their intent to climb without supplementary oxygen, only to turn to gas and extra support during their summit push.

Money for the environment

The Bill also lays the groundwork for a general environmental fund that will collect climbers’ money previously directed to specific goals, such as the garbage management fee and each foreigner’s $4,000 deposit, which is returned only if a minimum amount of solid waste is returned from the mountain.

Employees of the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee retrieve garbage bags from Everest Base Camp. Photo: SPCC

What is not mentioned

As far as we know, the proposed new regs do not mention the use of drones, which were such a great tool last year for the Icefall Doctors as they fixed the route across the Khumbu Icefall, or the always controversial helicopters, widely used to carry climbers and equipment from Kathmandu, but also used above Base Camp. There also remains no limit to the number of annual permits, which in recent years has totaled between 800 and 900.

The new bill specifies that the responsibility for coordinating search and rescue missions lies with the outfitters. It also states that missing climbers whose remains are not located will be declared dead in one year.

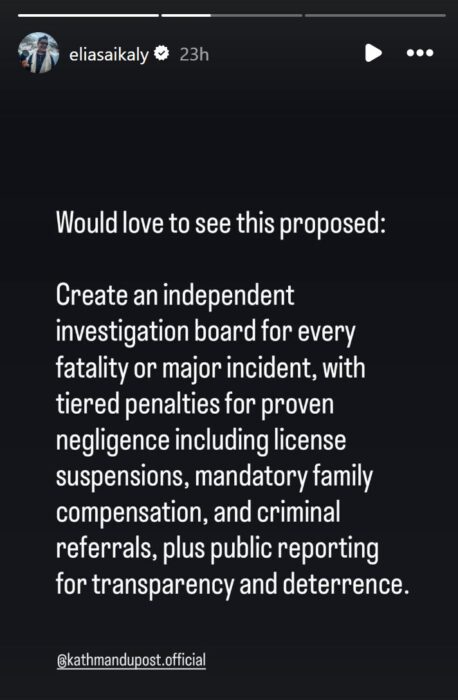

Climber/filmmaker Elia Saikaly has proposed an addition:

Elia Saikali/Instagram

No time for this spring

The bill now moves to the House of Representatives (the lower house) after the March 5 elections, the Kathmandu Post explained. From there, it returns to the National Assembly (the upper house) before going to the President for signature into law. That means the bill will not take effect this season.

The delay may also prove beneficial for business in 2026, as those considering climbing Everest without prior experience on a Nepalese 7,000’er might hurry to do so this spring, before the new law comes into force.