Christina Lustenberger of Canada and Guillaume Pierrel of France went to New Zealand for a different kind of ski adventure. They found one of the scariest lines of their careers.

After climbing the east face of Aoraki/Mount Cook’s central peak (3,717m) up the rarely repeated Jones route, the pair “pushed each other out of their comfort zones” down a steep, insanely icy line. Their route links ramps and gullies on a 1,000m face.

Learning from a failed attempt

At 3,727m, Aoraki is the highest peak in New Zealand. Located in the Southern Alps (the range running along the Southern Island), its relatively low altitude is deceiving. This serious challenge features hanging glaciers, high exposure, and fierce winds.

Lustenberger and Pierrel reached the area in September and started looking for a ski line. They had plenty of time to wait for a weather window. However, high winds thwarted the pair’s first attempt on October 11.

“As the route gets into the most difficult terrain, the winds picked up to gale force, turning the snow into ice and forcing us to retreat,” Lustenberger told ExplorersWeb. “We turned around and skied the lower spine of the mountain, and that was when Gee [Pierrel] saw a skiable exit for the route we had in mind. It was a little clean access point that connected two snow ramps at the bottom of the mountain’s flank.”

But the team, Lustenberger, Pierrel, and photographer Mathurin Vauthier, still had to wait out another stormy spell. This rough patch of weather only allowed for short climbs and descents on nearby Mount Vancouver.

Finally, on October 17, they set off toward their main goal.

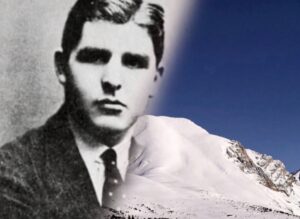

Christina Lustenberger and Guillaume Pierrel. Photo: Mathurin Vauthier

Climbing in purple light

The pair started at 2 am. They climbed under October’s full moon, known as the Hunter’s Moon, with the sky colored purple by a magnificent Aurora Australis.

They took shifts leading the pitches up the face, from a wide bergschrund and along ramps of hard snow to the summit of Aoraki’s middle peak, which they reached at 7:45 am.

“We made a bit of time, hoping the face would warm up and at least part of the snow would soften, then started down,” Lustenberger said. “Everything about that day was super engaging, very intense, a unique experience.”

“The [ski] line required precision in every movement, demanding a true collaboration with your partner and the wild surroundings you are playing in,” the team wrote on their social media.

In other words, the incline and snow conditions allowed no mistakes.

Trust

“As soon as we saw that the top section was skiable enough, we convinced ourselves that we really could open a new route there and that this was the right time to do it,” Pierrel said.

“First of all, you must commit…we trusted each other and went down. Then, during the descent, you just bring out all your skills and knowledge and try to make the descent as safe as possible,” Pierrel continued.

“We worked super well as a team,” Lustenberger said. This is significant because it was the first time the two athletes had skied together. The person in front has a lot of responsibility, and they took turns taking the lead during the descent.

“It was the first time we skied together, but when you pair up with the best skier on the planet — that is Christine — it’s pretty obvious that it is going to be fine,” Pierrel said. “She knows all the codes, all the rules, and she skis virtually everything.”

“For me, it was a game of deciding to [go for it] and then, when the steepness was harrowing, and one of us hesitated because we’re human, the other one would push you to keep going,” Pierrel explained. “In that sense, we were lucky to be a good match as a team in such demanding, serious terrain.”

The crux

“We had to find patches of skiable snow the whole way down, as the whole face just falls away with exposure, and the ski conditions changed from one turn to the next,” Lustenberger recalls. “Further down, the snow had warmed a bit, and we found conditions slightly more forgiving. But then, at the bottom of the face, we had that bergschrund. Crossing, or rather jumping it, right before the finish line was quite something.”

Lustenberger noted that the bergschrund had almost tripled in size since their previous attempt. During the ascent, it took a long time to look around for a passage. Jumping over it on the way down on their skis took a leap of faith.

“Gee [Pierrel] found a passage which was not exactly obvious, nor easy. It commanded a bit of a jump over the bergschund exposure,” Lustenberger said.

“It was only after crossing the bergschrund that we got free from the face and the grips relaxed; I sighed and had this feeling of lightness that comes from the release of what you have been so intensely focused on,” Lustenberger said.

Orienteering

In addition to the icy conditions, the main challenge was orienteering. The climbers had been carefully checking the face in different light, at different times of day, looking for snow features and exit points.

“I had taken some photos of the potential route with my cell phone. I checked them during the descent when we stopped to regroup. [We were] trying to identify features because when you’re up there, everything just falls away,” Lustenberger said.

Guillaume Pierrel. Photo: Mathurin Vauthier

Choosing the correct line was especially tricky on the upper half of the mountain. That area had been out of sight during the climb.

“We were following a system of ramps, and we got to a point where we had two options: go left or continue down the ramp onto what looked like more challenging terrain,” Lustenberger recalled. “We stopped there and we discussed the conditions, what we could ski or not ski, whether to go left or right. Gee [Pierrel] was confident and believed we could continue down the ramp, and I said, ‘OK, I trust you, I’ll follow,'” Lustenberger said.

“Skiing on-sight is also part of the adventure,” Pierrel said.

Christina Lustenberger. Photo: Mathurin Vauthier

The descent was done completely on skis, without rappelling. Only during the middle of a gully on pure ice did the skiers secure 30m of Dyneema rope with a nut on a crack to provide extra hold if needed. The rest of the way, they trusted their skills and the sharp edges of their skis.

Routes on the East face to the central summit. In yellow, the Jones route climbed on their ascent. In pink, the new ski line ‘Hunter’s Moon.’ Photo: Mathurin Vauthier

The best of a great year

Lustenberger describes the climb and descent as the best skiing she’s done all year. She even ranked it above the first-ever ski descent of Pakistan’s Great Trango Tower, completed with Chantel Astorga and Jim Morrison some months ago. She admits, however, that the two were quite different: Aoraki/Cook was more technical and exposed, while on Trango, the challenge was to find a continuous line of snow from top to bottom.

Next, Lustenberger will enjoy winter at home in the Canadian mountains. Here, Lustenberger, a former World Cup downhill skier, has skied many remarkable first descents, such as on Mount Nelson, Mount Ethelbert’s east face, and Niflheim.

“Perhaps my expectations were not as high as when traveling to the Andes or the Himalaya,” Chamonix-based Pierrel said. “Yet, I was impressed at the wild terrain, the hanging glaciers…and the super nice, helpful local skiers.”

Impressing Pierrel, an IUAGM guide, is not easy. He was part of the French team that skied down Gasherbrum II in 2021. Earlier this year, he finished two crazy-steep ski lines in the Alps: the north face of the Dru in the Chamonix area and Picco Luigi Amedeo on the Italian side of the Mont Blanc Massif, with Vivian Bruchez.