The Endurance set sail from Plymouth in 1914 with a crew of past and future polar icons aboard. But true fame only found the ship after she sank. In November of 1915, she was crushed by the ice, launching her former passengers into a legendary ordeal.

The ragged crew, led by Sir Ernest Shackleton, returned as heroes, immortalizing the ship Endurance in polar history. She was far from the first, or the last, ship to be caught and crushed by polar ice. Since the 2022 discovery of the wreck, however, researchers have been investigating further. A new study suggests that Endurance was doomed by her own design flaws.

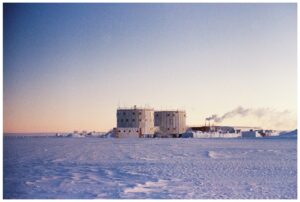

Now that we’ve found the wreck, we can examine forensically what killed her. Photo: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust

The strongest ship of her day?

As with any oft-mythologized historical incident, the 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition has its own established narrative, which is not always married to reality. Shackleton wrote in his own book, South, that his ship was one of the strongest polar vessels of the era. She had one Achilles heel — a vulnerable rudder — which failed, sinking the ship. Later writers took Shackleton at his word.

A research team led by Finland’s Aalto University combined archival research and structural analysis of the wreck to see if the Endurance was really designed to endure.

It wasn’t.

Originally named Polaris, the vessel was sponsored by former Antarctic commander Adrien de Gerlache, whose employment a young Roald Amundsen attempted to quit, while they were all still frozen into an Antarctic winter. I share this fact only to illustrate that having a ship he sponsored sink automatically was very much in line with Gerlache’s general history.

Built in Norway’s Framnæs shipyard, the vessel was sold to Shackleton at a loss. Originally intended for summer tourism in the Arctic, her flaws became fatal when they encountered Antarctic winter ice. The deck beams, which Endurance needed to withstand the compression of pack ice, were not strong enough. The hull was weakened by a long machine room and an absence of diagonal beams. The general shape of the ship was longer and less round than ideal polar vessels like the Fram.

Even on paper, ‘Endurance’ wasn’t built for compressive ice. Photo: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

A calculated risk

Researchers examined the wreck to see whether the flaws on paper manifested in reality. While at first glance the wreck seems to be mostly in one piece, in truth, she was shattered structurally. The deck beams were, indeed, too weak, and we can see that they buckled. The keel has been torn off completely, the closest thing to a killing blow. Most of the damage, however, is hidden by the mud of the seabed. Under the waterline, now the mud line, the ice will have done its worst.

Jukka Tuhkuri, a professor of solid mechanics at Aalto University and part of the team that discovered the Endurance, said in a press release that “even simple structural analysis” showed that the ship wasn’t designed for the ice. Early 20th-century shipwrights knew, he went on, how to build a ship that would hold up. “So we really have to wonder why Shackleton chose [Endurance].”

Archival records showed that Shackleton, at least, was aware of the defects. He knew the importance of diagonal beams and had recommended them in another ship. In a letter to his wife Emily, he admitted that Endurance was not as strong as Nimrod, his previous vessel.

The ship may not have been ideal for polar exploration, but in his defense, most polar vessels weren’t. Scott’s Terra Nova, for instance, was a refitted whaler that nearly foundered off New Zealand.

For Shackleton, time was short, with the first World War closing in, and money was tight. But as Tuhkuri says, we can’t say for sure why Shackleton chose Endurance.

Shackleton would make a similar gamble on his next, last voyage. Though the problem was not the ship, the Quest, but his own body. His heart, like the Endurance, gave out just as the expedition began.