Any list of almost-forgotten climbers who deserve to be remembered has to include French alpinist Nicolas Jaeger. Not only was he an outstanding mountaineer, but his disappearance on Lhotse Shar in 1980 was a real mystery.

Born in 1946, Nicolas Jaeger became a mountain guide in 1975, graduating as best in his class. He was also a doctor who specialized in high-altitude physiology.

Jaeger made more than 100 solo ascents in the Alps, with a particular focus on the Mont Blanc massif. These climbs included about 20 long, high-difficulty routes, including first and second ascents. In the Andes, he made eleven solo ascents, nine of them via new routes. In the late 1970s, he also did some new routes with partners.

The first cigarette on Everest’s summit

On May 8, 1978, Peter Habeler and Reinhold Messner did the first no-O2 ascent of the highest mountain in the world.

In the autumn of the same year, a French expedition came to Mount Everest. Led by Pierre Mazeaud, the team included French, Austrian, and German climbers. Mazeaud, Jean Afanassieff, Kurt Diemberger, and Jaeger (the expedition’s doctor) summited Everest with supplementary oxygen on Oct. 15. It was the first French ascent of Everest.

At the top, they removed their oxygen masks and spent 100 minutes at the summit. In classic Gallic style, Jaeger lit up an unfiltered Gitanes cigarette, possibly becoming the first person to smoke on top of the world. A rather peculiar person, Jaeger wanted to observe the effects of oxygen deprivation at 8,848m. He concluded that it wasn’t that difficult to sit there without an oxygen mask, but whenever he had to move, it was hard because of the hypoxia.

The next day, Jaeger and Afanassieff skied down the mountain from 8,200m to 6,500m in an hour. They continued from Camp 2 (6,500m) to Camp 1 (at 6,000m) in two hours. There, they stayed the night before descending down to Base Camp. At the time, it was a record height for a ski descent.

Jaeger on the summit of Everest, without cigarette. Photo: Nicolas Jaeger Archives

A heavy smoker confronts Nevado Huascaran

In 1979, Jaeger returned to the Andes and made some solo ascents as well as some excellent climbs with Brian Hall, Alan Rouse, and cameraman Philippe Charliat. He also decided to complete a solo survival experiment on Nevado Huascaran to study the body’s response to extreme altitudes.

During a two-month stay at 6,700m, Jaeger smoked 70 packs of cigarettes. He had two tents. In one, he took medical measurements and tested his body. He wrote the book Carnets de la Solitude about his experience. At the time, many people regarded his experiment as crazy. They saw no reason to spend 60 days at high altitude. Jaeger was an outsider.

Jaeger in his tent on Nevado Huascaran in 1979. Photo: Nicolas Jaeger Archives

Alpinism’s future ‘big problem’

During his 1978 Everest ascent, Jaeger admired the South Face of Lhotse. From that moment, the face — which Messner called a “problem for the year 2000” (in other words, the future’s biggest climbing challenge) — became lodged in Jaeger’s head.

By 1980, Jaeger was ready. According to the American Alpine Journal, his ambitious plan was to make the first ascent of the 3,050m South Face of Lhotse, supported by two friends. He would then climb the West Ridge of Everest alone, without bottled oxygen or sherpa support.

“So far, the major achievement in solo climbing is Messner’s Nanga Parbat in August 1978 by a new route,” Jaeger said before his expedition. “The Lhotse Face is higher and more difficult.”

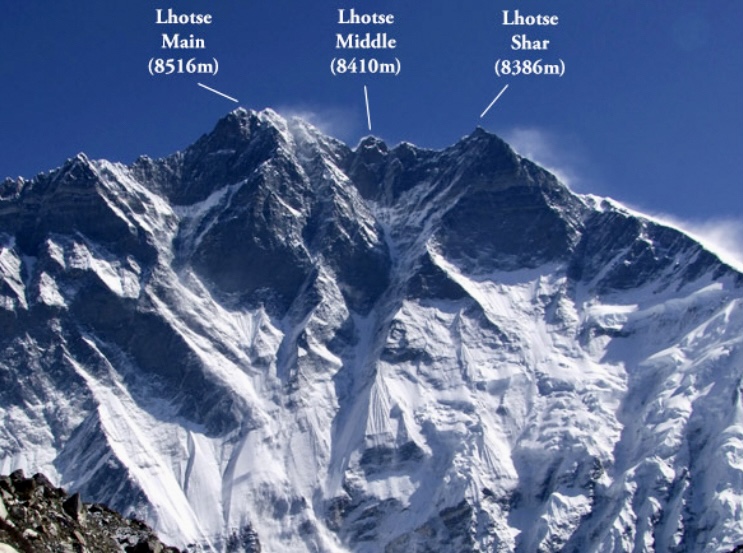

Lhotse Main, Lhotse Middle, and Lhotse Shar. Photo: Russian Climb

Accompanied by Nicolas Berardini and Brigitte Steinmann, Jaeger arrived in the Himalaya in the spring of 1980. For acclimatization, Berardini and Jaeger first attempted Ama Dablam’s West Face, reaching 300m below the summit.

Next, they went to Baruntse, which Berardini and Jaeger summited on April 7 via the North Face. The Himalayan Database marks both climbs as illegal. From there, Jaeger went to the South Face of Lhotse.

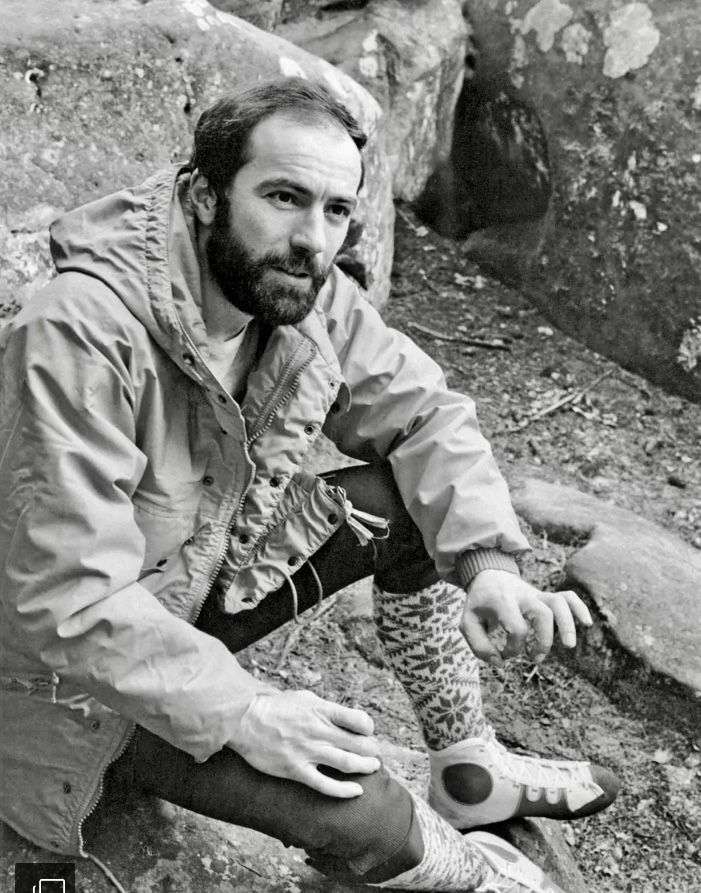

Jaeger rock climbing in Fontainebleau, France. Photo: Janine Niepce-Roger Viollet

First attempt

On April 16, Jaeger first attempted the South Face direct. He made it to 6,500m but turned around because of avalanche danger. He returned to Base Camp on April 20. On his next attempt, he decided he would go further right on the South Face. That meant ascending via Lhotse Shar.

According to a Himalayan Database report, Jaeger told those in Base Camp that he wanted to attempt a huge traverse. From Lhotse Shar, he would go to Lhotse Main via the then-unclimbed Lhotse Middle, before descending by the Western Cwm. He would even try Everest solo.

The traverse was an extremely committed project with a very low possibility of success. However, Jaeger believed in his strength and was confident he could spend many days at high altitude.

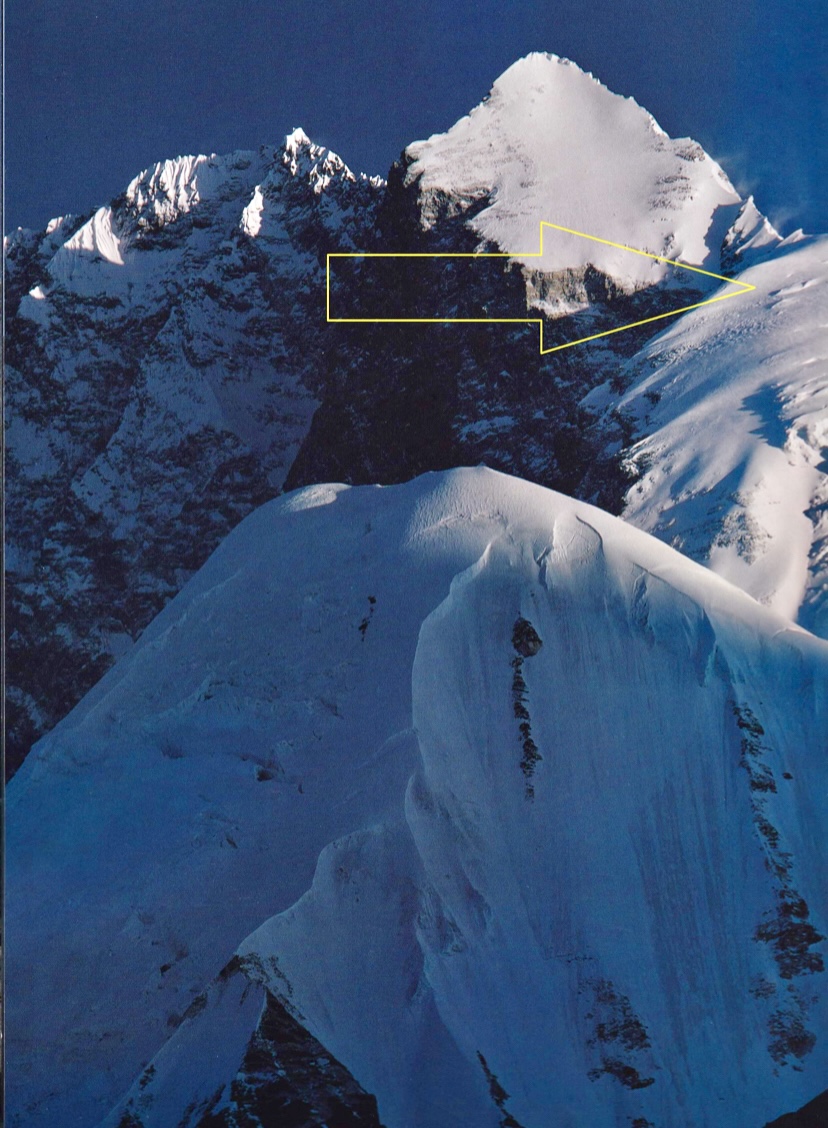

Lhotse and Lhotse Shar. Photo: Lluis Cabarrocas Ribas/Wikimedia

Lhotse Shar

Lhotse Shar (8,382m) is a subsidiary peak of 8,516m Lhotse. It can’t be considered an independent mountain, yet this east peak of Lhotse is difficult to climb and is one of the most dramatic subsidiary peaks in the world.

According to The Himalayan Database, an American-Austrian-Swiss party led by Norman Dyhrenfurth first scouted the peak in 1955. The first serious attempt on Lhotse Shar was in the spring of 1965, by Japanese alpinists from the Waseda University Alpine Club. Hisao Yoshikawa’s team attempted the southeast ridge but had to abandon their attempt at 8,150m because of an impassable gap.

Two members of an Austrian party led by Siegfried Aaberli made the first ascent of Lhotse Shar on May 12, 1970. Using bottled oxygen, Sepp Mayerl and Rolf Walter topped out via the southeast ridge.

Four climbers from Czechoslovakia did the first no-O2 ascent in 1984. Zoltan Demjan, Peter Bozik, Josef Rakoncaj, and Jaromir Stejskal reached the summit on May 20 (Demjan) and May 21 (the other three) by a new route via the south face.

To date, of the 36 teams that have attempted Lhotse Shar, only nine have succeeded, via four routes. Since the first ascent, 24 climbers have summited, including 13 without bottled oxygen.

A rare peak even today, Lhotse Shar was last ascended in 2007. Ten climbers have lost their lives on its slopes. Lhotse Shar’s death rate is quite high.

Jaeger disappears

After his Lhotse South Face attempt, Jaeger started up the southeast ridge of Lhotse Shar on April 25. Alone, he carried sufficient food for 8 to 15 days. Cameraman Bill Rosser filmed the ascent from below.

Everest and the gigantic South Face of Lhotse Main, Lhotse Middle, and Lhotse Shar from the upper Hongu Valley. Photo: Mountains of Travel

Well-acclimatized, Jaeger ascended relatively fast and bivouacked at about 8,000m on Lhotse Shar, Rosser observed through his telephoto lens. On April 27, Rosser spotted Jaeger at 8,200m climbing at amazing speed.

But the weather turned bad, and strong winds hit the mountain. Rosser did not see Jaeger again.

According to Edward Morgan, author of Lhotse South Face – The Wall of Legends, Berardini, Steinmann, and the rest of the expedition had already moved to Everest Base Camp to wait for Jaeger in case he succeeded in traversing Lhotse. But Jaeger never returned from the heights.

Jaeger had said that if he didn’t come back after 15 days, a search operation shouldn’t be carried out as it would mean he was dead. Bad weather persisted for six days, and a helicopter search found no sign of him. Soon after, the search was stopped per his family’s wishes.

For most, this was the end of the story. Jaeger had disappeared and was never found. For 39 years, even Jaeger’s family believed this was all the information they’d ever know about his final climb. But three years after Jaeger’s fatal 1980 expedition, there was a discovery that went under almost everyone’s radar.

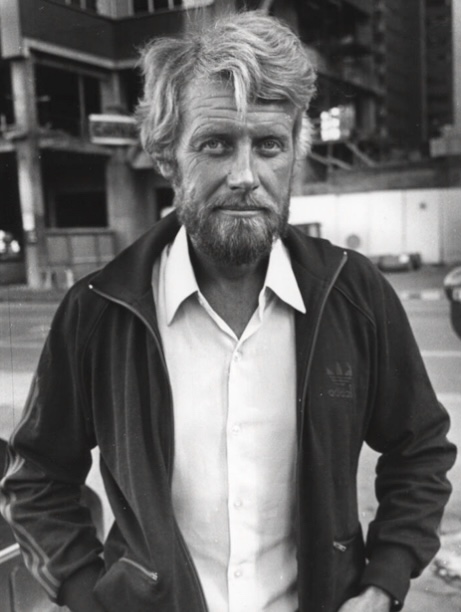

British-Canadian Roger Marshall. Photo: Digital Collections University of Calgary

The Canadian clue

While researching the Tomo Cesen case in 2013-2014, mountaineering researcher Rodolphe Popier found a note in The Himalayan Database that mentioned the book Canadians on Everest: The Courageous Expedition of 1982.

The book, published in 2006 and written by Bruce Patterson, one of the Canadian climbers, told the story of the first successful Canadian ascent of Everest. The book mentions that climber Roger Marshall found Nicolas Jaeger’s body in 1983 on Lhotse Shar. The body was in a tent less than 500m below the summit.

Lhotse Shar. Photo: Jong Hun Kang

When we asked Popier about this, he said that he asked mountaineering writer Bernadette McDonald for help finding the book. He then checked if the description of the body matched Jaeger.

News of Marshall’s discovery of Jaeger’s body didn’t make it to France at the time. The internet was still in its early years, and climbing journals weren’t yet digitized. Popier also points out that only a few bilingual readers from Europe read the American Alpine Journal, and alpine communities in each country were still very inward-looking. So news of the discovery went under most people’s radar.

In 2019, Helene Jaeger-Defaix, Nicolas Jaeger’s daughter, eventually heard about the whole story from a friend of Popier, Charlie Buffet.

More recently, writer Virginie Troussier wrote a book on Jaeger (L’homme qui vivait haut: La passion du Docteur Jaeger). Troussier talks about Marshall’s discovery of the body. Edward Morgan also dug into the story for the second edition of the essential Lhotse South Face.

Where the tent and the frozen body of Nicolas Jaeger were reportedly found. Photo: Rodolphe Popier

The tent and Jaeger’s body

Popier told ExplorersWeb that Roger Marshall talked about a yellow-blue tent where he found Jaeger’s body. The tent wasn’t Jaeger’s but belonged to a previous expedition, possibly the 1965 Japanese attempt. Alternatively, the tent could be from the 1970 first-ascent team or possibly the 1971 Korean team.

Cameraman Rossner said he spotted Jaeger for the last time at about 8,200m. According to Popier, after checking maps and photos of the upper ridge, there are wide slopes from 7,143m to 8,019m. He believes that the tent was somewhere close to that 8,019m point.

This means that Jaeger could have reached 8,200m, and then turned around to this improvised refuge at about 8,000m. Unfortunately, Marshall died on Everest in 1987 so the theory can’t be confirmed.

Jeager’s legacy is important for the history of mountaineering. As Gaston Rebuffat wrote in the Alpine Journal UK after Jaeger’s disappearance, Jaeger “was a passionate man, who was at the same time lucid and stable, having great experience of mountains and also of his strengths, a man looking to the future.”

You can view some of the last footage of Jaeger here.