After 49 days and over 1,100km of skiing through Canada’s most remote terrain, Norwegian Borge Ousland and Frenchman Vincent Colliard have completed the first unsupported north-to-south crossing of Ellesmere Island.

The pair reached King Edward Point, the southernmost point on the island and the end of the crossing, on June 13. They then skied for two more days to reach the Inuit community of Grise Fiord on June 15.

The journey was part of the duo’s Ice Legacy project, a long-term initiative to traverse the world’s 20 largest ice caps. On this latest journey, they crossed the Grant, Agassiz, and Prince of Wales Ice Caps, leaving only four ice caps remaining in their global undertaking.

The expedition began on April 27, following a weather delay in Resolute Bay. From Ward Hunt Island, just off Ellesmere’s northern coast, Ousland and Colliard skied east to Cape Columbia. This was the official start of the crossing and is the northernmost point of Ellesmere Island and North America. From here, they turned south into the island’s interior, hauling 130kg sleds behind them containing all their food and equipment, and foregoing any resupply or external support.

Early polar bear encounter and heavy loads

Borge Ousland in full flow. Photo: icelegacy.org

The pair’s early days included an encounter with a polar bear, which approached within 12m of them, while on sea ice near Cape Columbia. Colliard described the bear as “very curious plus plus” before Ousland used a signal flare to scare it away.

Ousland and Colliard’s feat is a first in the history of Ellesmere Island expeditions. While two vertical traverses have previously been completed — John Dunn’s in 1990 and Bernard Voyer’s in 1992 — both had resupplies. In 2011, Jon Turk and Erik Boomer completed a full circumnavigation of Ellesmere by ski and kayak, but also relied on external support. Ousland and Colliard’s expedition is the first to complete a full north-south route unsupported.

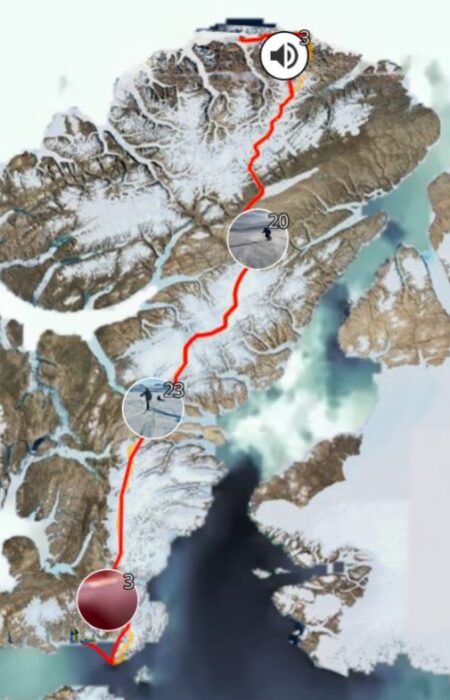

Ousland and Colliard’s GPS tracks. Map: icelegacy.org

Limited wind assistance

The route offered few flat sections, requiring repeated climbs and descents across glacial domes, riverbeds, canyons, and rocky terrain. Colliard reported persistent headwinds throughout the expedition, limiting their use of Beringer ski sails to just 60km. They thus completed most of the journey under their own power.

Borge Ousland from above. Photo: icelegacy.org

Progress remained steady, despite occasionally difficult conditions. Deep snow on the Grant Ice Cap slowed their early pace to about 14km per day, but once they reached the mostly snowless ground between the Grant and Agassiz Ice Caps, they detoured along the frozen Dodge River to preserve their sleds. There, they managed to increase the pace to 20km a day.

The expedition was not without risk. On day 26, while exiting the Agassiz Ice Cap, Colliard fell into a crevasse. He was uninjured, but later acknowledged that fatigue and overconfidence may have contributed to the incident.

The pass is a ribbon of snow that carves its way through steep slopes and deep canyons. At one point in the early 20th century, a glacier blocked the one route through the pass, and some explorers dubbed it Hell Cleft. Photo: Weber Arctic

Crossing Sverdrup Pass

After finishing the Agassiz Ice Cap, the duo faced a challenging descent and ascent through a steep gorge east of Canon Fiord, and then crossed Sverdrup Pass, named after Norwegian explorer Otto Sverdrup, who overwintered on Ellesmere from 1898-1902. The pass is often rocky and slow going. Ousland and Colliard, however, found it covered in snow, allowing them to continue skiing without having to portage their sleds.

Ousland, left, and Colliard in good spirits as they reach Grise Fiord. Photo: icelegacy.org

After reaching and safely crossing the Prince of Wales Ice Cap, they descended through Makinson Inlet and Bentham Fiord and crossed the Manson Icefield and the Jakeman Glacier. Ousland and Colliard reached King Edward Point on June 13, officially completing the unsupported crossing. They then backtracked west for a final two-day push across sea ice to Grise Fiord, where they can recuperate and fly back out to civilization.

Photo: icelegacy.org