Peter Hamor has arrived in Kathmandu for his planned first ascent of the 7,318m west face of Kabru South. His wife Maria will hike with him in the Kangchenjunga area for the next three weeks.

“It will be a good acclimatization for me,” he told ExplorersWeb about his hike. He will also scope out the current conditions on Kabru South. Then in mid-April, his wife flies home, and climbing partners Nives Meroi and Romano Benet join him. They set off for Kabru on April 14.

A huge unclimbed face

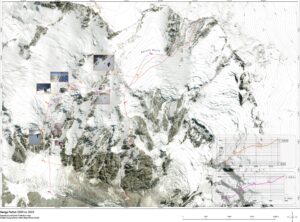

“Rathong and all the Kabru peaks form a magnificent ridge,” Hamor explained. “The huge unclimbed west face first caught my attention in 2012. Last year, I sat under it again, trying to find a logical and at least somewhat safe line to the top.”

Hamor didn’t say whether he now has any particular line in mind.

Kabru South’s west face. Photo: Peter Hamor

“We’ll bring along snow spikes, ice screws, pitons, Friends, nuts, and slings with us for the ascent…It will definitely be great alpinism, similar to the Northwest Ridge of Dhaulagiri,” said Hamor. “The first 700-800 meters will be crucial. Then it will only be dangerous :-)”

The team is not aiming for a pure alpine-style climb but will try to go as light and as fast as possible. They expect to fix ropes in certain passages, but exactly where and how much rope will depend on conditions.

“At least, that is our original plan,” Hamor said. “Every day spent on this wall with good friends will be exactly what Himalayan climbing [is about].”

Bitter Kangchenjunga

Hamor has summited all the 8,000’ers except for Manaslu without supplementary oxygen and also made a second ascent of Annapurna. Now, in the company of kindred spirits on a slightly lower mountain, the Slovak climber hopes to put behind him his disappointing experience on Kangchenjunga last year.

Hamor had already summited Kangchenjunga in 2012, but he returned to the mountain last spring with two goals in mind. First, he wanted to support climbing partners Horia Colibasanu and Marius Gane until at least Camp 4.

“At that point, I planned to split and try to climb Yalung Kang, where I would decide whether to traverse to the main peak or descend to C4,” Hamor said.

But plans often change in the mountains. This time, the unexpected hurdle was administrative and economic.

“I was very surprised to learn that the Nepalese authorities consider each peak of Kangchenjunga as a separate 8,000’er,” he said. “This needed additional fees for the permits, and even an additional liaison officer, which was far beyond my budget.”

Hamor, Gane, and Colibasanu in a high camp on Kangchenjunga last year. Photo: Horia Colibasanu

At least, he was able to climb with Colibasanu, who finally reached the summit without supplementary O2 on May 7. Hamor and Gane went more slowly and eventually waited in the last camp for him to return.

“I was so happy!” said Hamor about his friend’s success. “Horia climbed the same route I had followed in 2012, and we closed a chapter that had begun 10 years before.”

In 2012, while attempting Kangchenjunga with no previously fixed route, Peter Hamor took a different line on the upper sections than the one followed by Colibasanu, Nives Meroi, and Romano Benet. Hamor’s route was the correct one, and he reached the true summit alone.

The other three eventually realized that they had picked the wrong couloir and eventually had to turn down. Peter Hamor’s was the only Kangchenjunga summit that year.

8,000’ers are now different mountains and draw different people

Asked how Kangchenjunga has changed over the last 10 years, Hamor said bluntly, “It’s unrecognizable.”

In 2012, we climbed the peak as a foursome with Horio, Nives and Roman, and we had the mountain to ourselves. In 2022, it looked exactly like any other 8,000’er in Nepal: I didn’t even know how many people were in the base camp and how many ended up standing at the top. Helicopters, hundreds of oxygen bottles, lots of people, kilometers of fixed ropes, maximum comfort and service until the last camp, and experienced guides going with their clients to the top. This new trend, in my opinion, is a step, or rather a leap back, and has nothing to do with real climbing.

But, alas, what can be done? Times change and so do people. I am just glad that I was lucky enough to experience a different Nepal.

Nives Meroi and Romano Benet during the 2012 attempt on Kangchenjunga. Photo: kangchenjunga2012.blogspot.com.es