Modern Antarctica is a frozen desert, largely devoid of life except around the coasts. But this wasn’t always the case.

In 1833, naturalist James Eights found fossilized wood buried in the continent’s South Shetland Islands. The great polar explorers Shackleton, Amundsen, and Scott all found fossil wood, plants, and coal seams.

This is because dense rainforests once dominated Western Antarctica and Australia. Around 600 to 100 million years ago, they were part of the supercontinent of Gondwana. Then continental drift tore Antarctica and Australia apart and pulled Antarctica deep into the southern polar region.

But what happened to the great forests that covered it for so long? Could such a forest, subject to months of darkness and extreme conditions, possibly survive?

That’s what a team of researchers led by marine geologist Johann Klages set out to discover.

Robert Falcon Scott collected this piece of fossilized wood in Antarctica on his last expedition. Photo: The Natural History Museum, London

Pulling back the ice

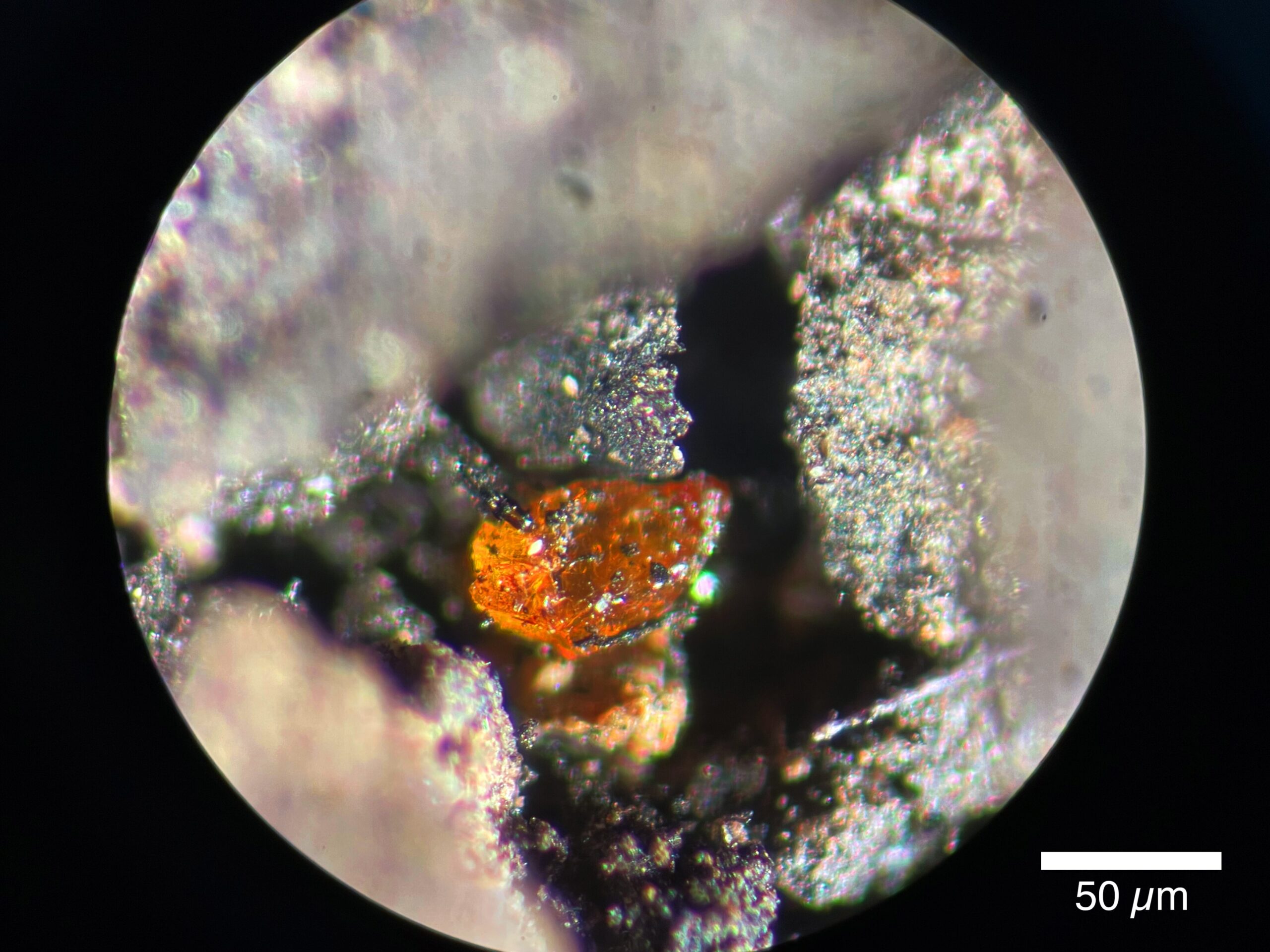

The researchers drilled into the seafloor off the coast of Western Antarctica and brought up a three-meter-long chunk of mudstone. It had rested underneath nearly 1,000m of frigid seawater and held something never before found in Antarctica: amber.

Amber, the fossilized resin of ancient plants, has turned up on every continent except Antarctica. Now with this new report, Antarctica joins the other six. The presence of resin also answers long-standing questions about the changing landscape of Antarctica as it moved south.

Scientists knew the mudstone had formed in the mid-Cretaceous, 92 to 83 million years ago. The amber proved that a wet, swampy forest existed in the South Polar Region only 90 million years ago.

A tiny sample of amber found in Cretaceous rock. Photo: Johann P. Klages

The polar forest

During the mid-Cretaceous, high levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere warmed the planet significantly, allowing lush plant life to survive even at the Poles. However, they still had to contend with the polar night. Researchers suggest that the large conifers that dominated this ancient forest entered periods of dormancy during the winter in order to survive, as subarctic trees do today.

The amber revealed another thing about these forests: Fires were frequent. Resin flows to form a sort of scab over damage to the tree. This damage can come from parasites, but it was more likely from fire. This makes sense, as the Cretaceous was extremely warm and marked by frequent volcanic activity.

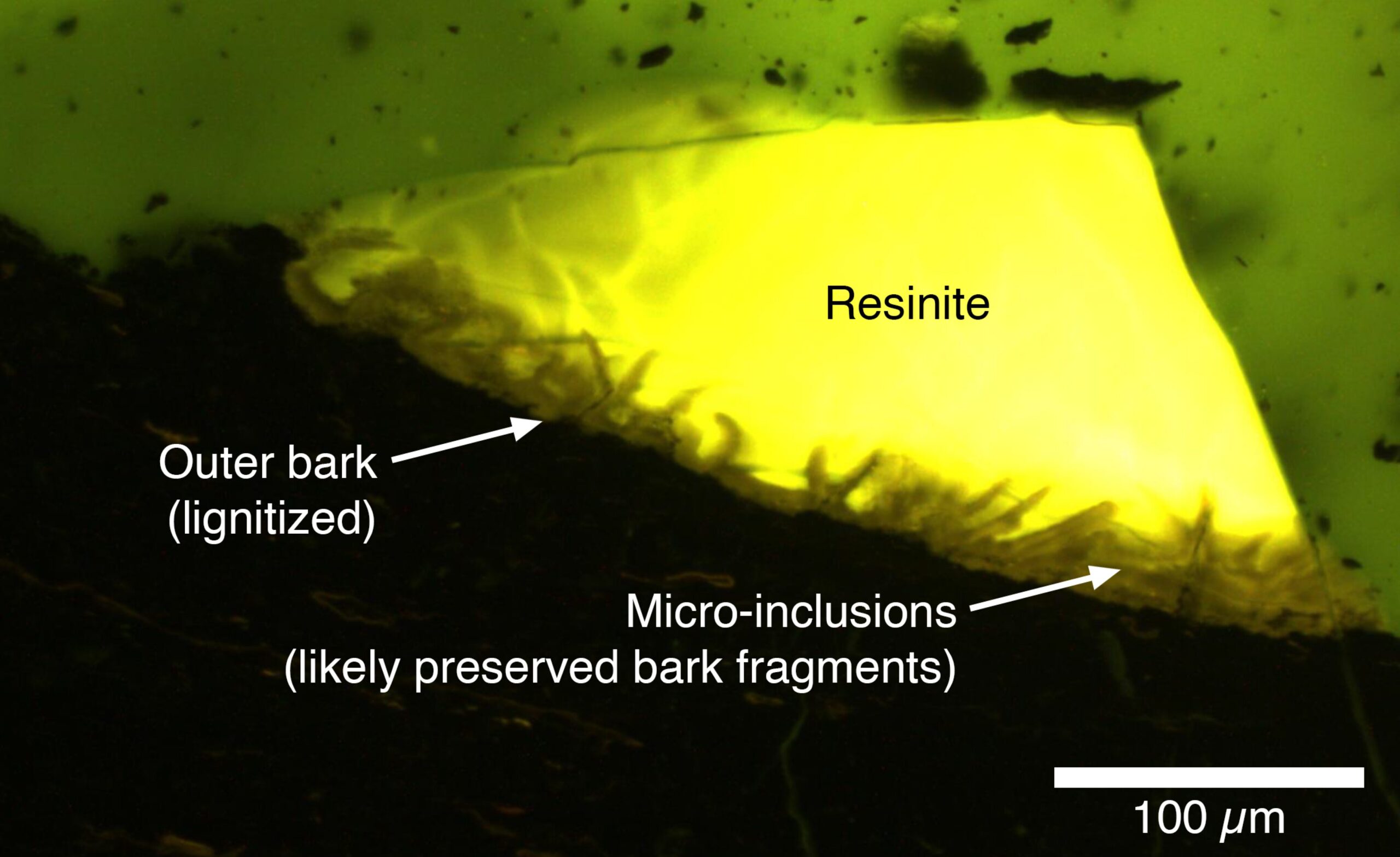

The same block of mudstone also contained preserved pollen, spores, and root systems. The amber not only shows that Cretaceous-era Antarctica supported plant life but also gives clues to the ecosystem of a primeval polar forest.

The block of mudstone likely still holds more discoveries. Klages’ team believes that ancient tree bark lies inside the golden amber fragments.

The tiny samples of amber, containing inclusions which may be tree bark. Photo: Johann P. Klages