Elizabeth Hawley was born in Chicago on Nov. 9, 1923. Today would have been her 102nd birthday. For over 50 years, she documented Himalayan expeditions from Kathmandu.

Hawley’s work for The Himalayan Database made her the arbiter of mountaineering truth, the “Sherlock Holmes of the mountaineering world.” We commemorate her birthday by revisiting some of her important investigations and disputes.

Verification process

Hawley’s power came from her post-expedition interviews with climbers, conducted in Kathmandu. She began this work in the 1960s, interviewing every major expedition to Nepal’s Himalaya (and later expeditions to Tibet) before and after their climbs.

“Even at the moment you’re checking in, after thirty hours of flying to Nepal, Miss Hawley knows you’ve arrived,” wrote Ed Viesturs in his book No Shortcuts to the Top. “The phone at the front desk rings, and you have no choice but to schedule a briefing.”

Over 7,000 interviews detailed more than 20,000 ascents on about 460 peaks. Her sessions were often called the “second summit” by climbers, who sat on her couch and answered her questions. Hawley asked them about the weather, the route, the color of the snow, what other mountains they could see from the top, the location of the prayer flags, and much more. If their answers didn’t add up, she marked the climb as “disputed” in her records.

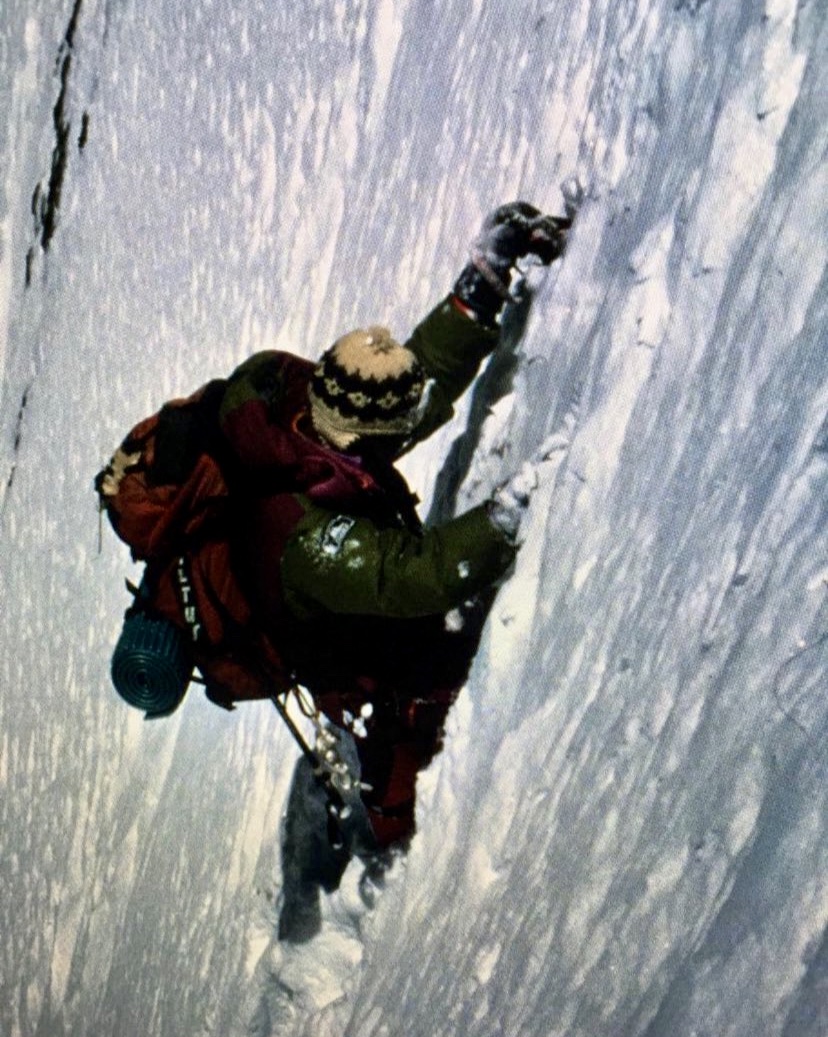

A young Elizabeth Hawley. Photo: Archives

Hawley’s database

Hawley’s database became the official record of Himalayan climbing. The Hawley stamp of approval was essential. Without it, the ascent was not proven or accepted. Her rejections were not personal, but principled, prioritizing precision over prestige. Mountaineering legends deferred to her. Miss Hawley, as many called her, was an institution.

Shisha Pangma

Shisha Pangma is the only 8,000m peak entirely inside Tibet. The main summit is at 8,027m. Its Central Summit is at 8,008m and is sometimes called the North Summit because of its position on the northern end of the summit ridge when accessed via the standard North Ridge route. A narrow ridge connects the main and central summits.

It takes about two hours to make the 250m traverse to the main summit over a sharp and exposed ridge. Hawley had a simple rule: only the main summit counted. Reaching the Central Summit was not enough. Two famous climbers learned this the hard way.

Anatoli Boukreev. Photo: Anatoli Boukreev

Boukreev

An elite high-altitude climber, Anatoli Boukreev worked as a guide on Everest in 1996 and helped save lives during the famous storm described in the book Into Thin Air. He climbed the 8,000m peaks without bottled oxygen, and speed was his style.

In September 1996, Boukreev went alone to Shisha Pangma. He left Base Camp, climbed quickly, reached the Central Summit, and returned to camp, all in just 28 hours. He even skied part of the way down. It was a remarkable solo climb, and Boukreev thought he had reached the real summit of the mountain.

When he returned to Kathmandu, he met Hawley. “I’ve got to go back, Elizabeth said I didn’t really climb it,” Boukreev told his friends with a smile. Boukreev wasn’t angry because he understood Hawley’s rule. His Shisha Pangma ascent remains officially incomplete.

Ed Viesturs on the summit of Manaslu. Photo: Himalman.wordpress.com

The careful American

Ed Viesturs is an American climber known for safety and planning. His goal was to climb all 14 8,000m peaks without oxygen. In 1993, Viesturs went to Shisha Pangma and reached the Central Summit. He knew Hawley’s rules, and he felt the climb was incomplete.

“After Miss Hawley had cross-examined me, she peered over her eyeglasses and said sternly, ‘You realize, don’t you, Ed, that you haven’t climbed Shisha Pangma? You’re going to have to come back and do it right,’ ” Viesturs wrote.

In 2001, he returned with Veikka Gustafsson and topped out on the true summit. Hawley accepted it, and Viesturs became the first American to finish all 14 8,000’ers without bottled oxygen.

Cho Oyu at sunset from the Tibetan Base Camp. Photo: Furtenbach Adventures

Cho Oyu

Alan Hinkes wanted to be the first British climber to summit the 14 8,000’ers. He finished his last one, Cho Oyu, in 1990, or so he thought. Cho Oyu has a large summit plateau, and the true highest point is a small bump at one end. Many climbers stop early and think nothing of it. When Hinkes met Hawley in Kathmandu, his answers raised doubts. He wasn’t sure exactly where he turned around, and other team members gave different stories in their interviews. Hinkes reached the edge of the summit plateau, not the summit.

Hawley marked the climb “disputed.” According to her records and later reports, this removed Hinkes from the official list of completers. The British Mountaineering Council supported him, but Hawley’s word carried more weight in the international climbing world. Hinkes never went back to Cho Oyu. He still defends his climb, but The Himalayan Database doesn’t count it as certain.

Juanito Oiarzabal. Photo: Wikipedia

A stickler

Hawley respected Spanish climbers Juanito Oiarzabal and Inaki Ochoa de Olza. With her peculiar style, she noted their honesty:

“Those conscientious about not making false claims included two Spanish, one on Dhaulagiri I and the other on Lhotse. Juanito Oiarzabal, who is a stickler for veracity amongst mountaineers and had blown the whistle on some errant ones, had a problem about the top of 8,167m Dhaulagiri.”

Hawley noted that Oiarzabal felt he didn’t reach the true summit. He came to an upright aluminum pole on the normal northeast-ridge route and was told that this point was considered the summit. Numerous climbers had claimed success based on having reached the pole.

“But for him, this was not the true summit…So he went all the way back up again. He made another summit push, was turned back by high winds, and only on May 22 did he get beyond the pole by a different line above 8,100m and satisfy himself that he had really summited Dhaulagiri I,” Hawley wrote.

Ochoa de Olza was on the normal route of Lhotse when he arrived at a point probably only 30m from the summit. However, he realized his eyes had frozen in the -35°C cold and he couldn’t continue.

“He didn’t claim to have reached the summit, although he certainly was very, very close,” Hawley wrote.

Inaki Ochoa de Olza. Photo via Sebastian Alvaro

Oh Eun-sun

In 2010, South Korean climber Oh Eun-sun claimed to be the first woman to climb all 14 8,000’ers. Her last climb was Kangchenjunga in 2009. However, her summit photo showed a ridge, but not the true summit. Hawley spoke to the Sherpas, who told her that the team turned back early because of bad weather. Hawley ruled the climb “unlikely.”

The Korean Alpine Federation agreed with Hawley, and Oh Eun-sun’s record was expunged. Spanish climber Edurne Pasaban finished her 14 peaks series in 2010 and became the first woman with a verified record on all the 8,000’ers.

Why Hawley mattered

Miss Hawley was not a judge in a court; she was a journalist who kept records. Climbers wanted her approval more than a certificate. Messner called her “the only authority” on Himalayan records. According to the book I’ll Call You in Kathmandu by Bernadette McDonald, Messner said Hawley’s database was more honest than any government list.

Miss Hawley with Edurne Pasaban. Photo: Turiski

Legacy

Hawley died on Jan. 26, 2018, at the age of 94. She passed away in a hospital in Kathmandu after a short illness. News of her death spread quickly among climbers and journalists. The American Alpine Club called her “the conscience of the Himalaya.” Even Nepali officials, whom she had sometimes criticized for loose permit rules, paid tribute to her work.

Hawley’s greatest achievement was transforming her notes into The Himalayan Database. In 1992, she partnered with Richard Salisbury, and more than 10,000 hours were digitized. Published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, it became the gold standard for mountaineering record-keeping.

As Dawa Steven Sherpa said, “one of her biggest contributions is keeping mountaineers honest.”

The Himalayan Database records every expedition since the 1950s to peaks over 6,500m in Nepal. By the time of Hawley’s death, it listed more than 60,000 climbs, 10,000 summits, and every known death. After she retired from daily interviews, her assistant Billi Bierling took over the work. The database is now digital and run by a small team at the Mountain Heritage Institute in Kathmandu. It is updated each year with new permits, summit reports, and fatality details, although without the strict scrutiny that characterized Hawley’s work.

U.S. Ambassador Peter Boddle called Hawley a “treasure” for deepening ties between the U.S. and Nepal. In 2014, a 6,182m peak was named for her, though Hawley thought it was a joke because she didn’t like naming mountains after people.

Elizabeth Hawley. Photo: Misadventuresmag

Further reading

For a clear and honest account of her life, we recommend reading I’ll Call You in Kathmandu: The Elizabeth Hawley Story by Bernadette McDonald. The book is based on interviews with Hawley and with Bierling. It explains how she started the database, why she questioned summit claims, and how she lived alone in a small Kathmandu apartment while running the most trusted database in mountaineering.

We also recommend the American Alpine Club’s remembrance piece.

Hawley never climbed high mountains, but she made sure that the stories told about them were true. She is sorely missed.

Elizabeth Hawley (1923-2018). Photo: American Alpine Club