Today, 104 years ago, legendary French alpinist Gaston Rebuffat was born.

One of the most celebrated mountaineers of the 20th century, Rebuffat was known for his bold new routes in the Alps, his role in the first confirmed ascent of an 8,000m peak (Annapurna I in 1950), and as the first person to climb all six great North Faces of the Alps. He wrote several influential mountaineering books and produced films that captured the essence of alpinism.

Early climbs

Rebuffat was born on May 7, 1921, in Marseille, France. He started climbing at 14 in the Calanques, a rugged coastal area near his hometown. In 1937, at 16, he joined the French Alpine Club, where he met Lionel Terray, a future climbing partner. Rebuffat visited Chamonix for the first time in 1937, and the Alps soon became his focus.

During World War II, Rebuffat took his climbing to a new level. In 1942, he graduated from Jeunesse et Montagne, a French youth training program, and received his mountain guide certification (despite being two years younger than the minimum age requirement of 23). In 1944, Rebuffat became an instructor for the French National Ski and Mountaineering School (ENSA) and the High Mountain Military School.

By 1945, he was focused on guiding clients in the Alps, fulfilling his desire to live in the mountains full time. He joined the prestigious Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix.

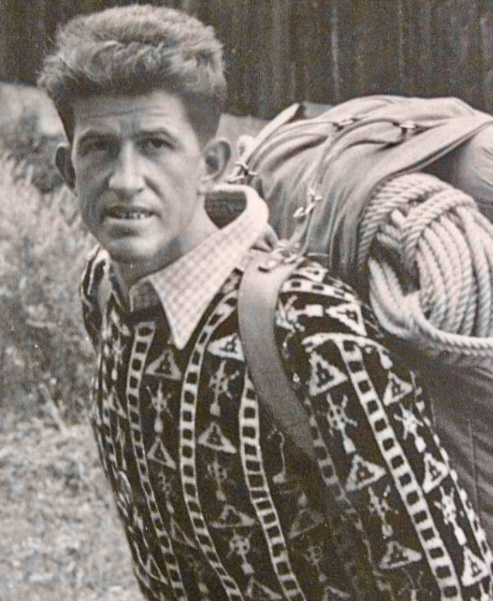

Gaston Rebuffat. Photo: Chamonix-guides

Climbs in the Alps

Rebuffat’s climbing career in the Alps was outstanding, with over 1,200 ascents classified as difficult or very difficult. In the 1940s, Rebuffat tackled some of the Alps’ most challenging peaks, alongside partners such as Terray and Louis Lachenal. By the end of the 1940s, Rebuffat was among France’s elite mountaineers.

In the 1940s and 50s, Rebuffat established approximately 40 significant first ascents via new routes. These included routes on the Aiguille du Midi, the Drus, and Aiguille du Roc. His new lines were known for their elegance and technical challenge, and reflect his philosophy of climbing in harmony with the mountain rather than conquering it.

The six North Faces of the Alps

Rebuffat finished his most celebrated achievement in 1952. The North Faces of the Matterhorn, Eiger, Grandes Jorasses, Piz Badile, Drus, and Cima Grande di Lavaredo are well known for their steepness, difficulty, and unpredictable weather.

Rebuffat began to plan his first North Face, the Grandes Jorasses, in 1938, when he was only 17 years old. The first ascent — by Italians Riccardo Cassin, Gino Esposito, and Ugo Tizzoni — inspired him.

On Rebuffat’s first attempt, in 1943, bad weather forced him to retreat. Finally, in July 1945, he succeeded, climbing the Walker Spur with Edouard Frendo in three days with two bivouacs. This marked the second ascent of this route.

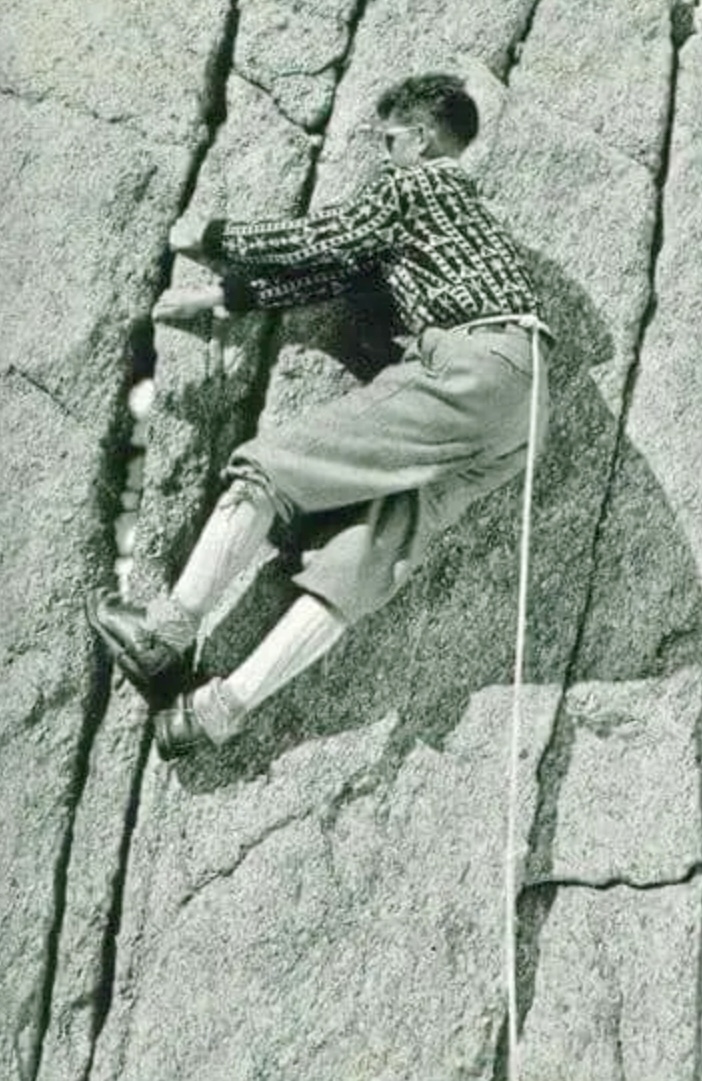

Gaston Rebuffat in the Alps. Photo: Sendas y Cumbres

In August 1946, Rebuffat guided Belgian amateur mountaineer Rene Mallieux up the North Face of the Petit Dru. They climbed fast to reach the summit by nightfall, bivouacking on the descent and attending the Chamonix Guides’ Festival the next day. The one-day ascent showcased Rebuffat’s efficiency and guiding skills.

In the summer of 1948, Rebuffat guided a client up the northeast face of Piz Badile in the Bregaglia Alps. Despite a severe lightning storm, they reached the summit the following day. They followed the Cassin Route, first ascended in 1937.

Rebuffat’s fourth North Face came in 1949 when he climbed the Matterhorn twice, first with Raymond Simond, and later with other partners (though some sources mention only one ascent). He targeted the Schmid Route, first climbed in 1931.

The same year, Rebuffat ascended the North Face of Cima Grande di Lavaredo in the Dolomites, guided by Italian Gino Solda. This ascent followed the Comici-Dimai Route, first climbed in 1933.

In July 1952, Rebuffat completed his quest with the North Face of the Eiger via the Heckmair Route. He climbed with Paul Habran, Guido Magnone, Pierre Leroux, and Jean Brune.

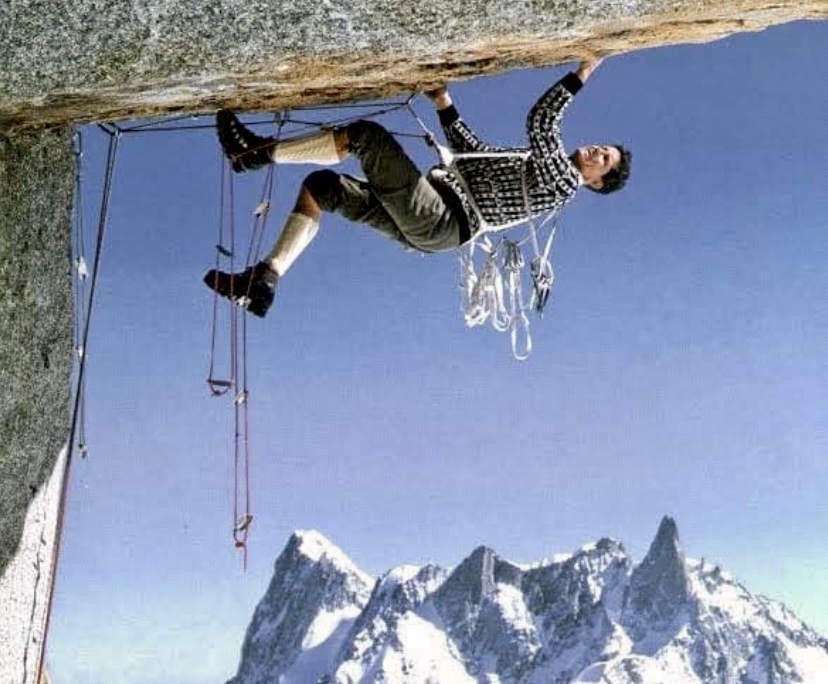

Rebuffat on Gros Rognon. Photo: Alta Montana

Annapurna I

In 1950, Rebuffat joined a French expedition to Annapurna I. Led by Maurice Herzog, the team included Rebuffat, Terray, and Lachenal, among others. The expedition started in March, but the ascent only began in May.

The French party established a base camp and four intermediate camps, the highest at 7,400m. On June 3, Herzog and Lachenal summited and became the first two people in the world to reach the top of an 8,000m peak. Rebuffat and Terray didn’t summit, but played a critical role during the descent.

While summiting was a historic triumph, the descent turned into an ordeal, marked by frostbite, snowblindness, avalanches, and navigational errors. Rebuffat helped to ensure the survival of frostbitten and disoriented teammates during the harrowing retreat.

Herzog and Lachenal reached the top around 2 pm and started to descend immediately. The weather was clear but very cold, with temperatures estimated at -40°. Herzog somehow lost his gloves while handling equipment, exposing his hands. Lachenal, impatient to descend quickly in the worsening conditions and with his own frostbite concerns, slipped and tumbled 100m down the slope. Miraculously, he stopped short of a fatal drop, but the accident left him shaken, with one crampon missing, and his ice axe gone. His feet, already numb from prolonged exposure, were deteriorating rapidly. Both men were in a very bad state as they struggled toward Camp 5 at 7,440m, where Rebuffat and Terray awaited.

Gaston Rebuffat and a climbing partner in the Mont Blanc Massif. Photo: Gaston Rebuffat

Meeting Rebuffat and Terray

Rebuffat and Terray had climbed to Camp 5 earlier that day, expecting to support Herzog and Lachenal or possibly attempt the summit themselves if conditions allowed.

When Herzog arrived at the high camp alone, Rebuffat and Terray were relieved, but then alarmed when they shook his hand. Herzog’s hands were frozen solid, white, and lifeless.

Rebuffat and Terray started to massage Herzog’s frostbitten hands and feet, hoping to restore the circulation, but their efforts had little result. Hearing some cries from below, Terray ventured out of the tent into the dusk and located Lachenal, who had missed the camp and was 200m down the slope. Terray guided Lachenal back to Camp 5. Lachenal’s feet were frozen, and he was disoriented from his fall and the altitude.

Rebuffat and Terray worked through the night to keep Herzog and Lachenal warm, using their body heat. Herzog’s hands and feet were turning black, and Lachenal’s toes were stiffening. Aware that the team needed to descend urgently for medical attention, Rebuffat helped organize the group for the next day’s descent.

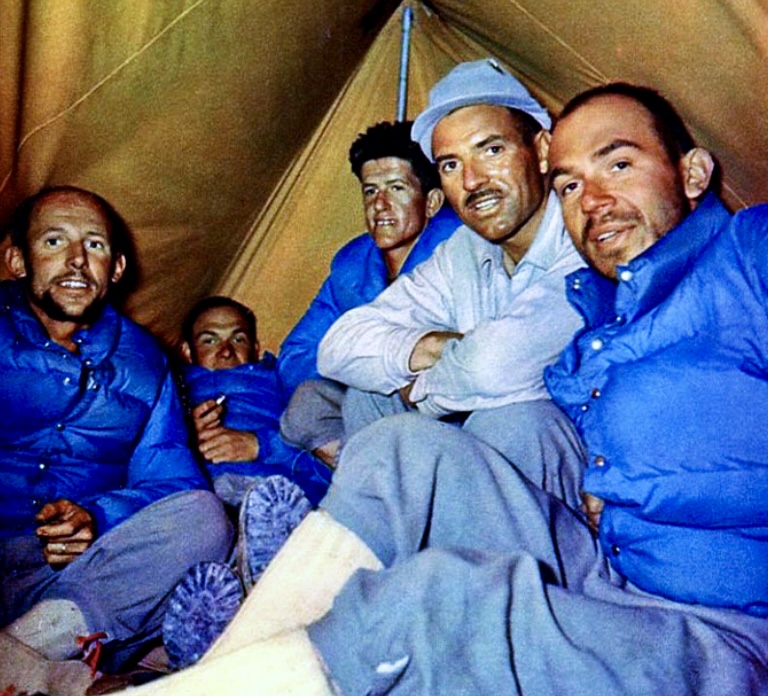

From left to right: Louis Lachenal, Jacques Oudot, Gaston Rebuffat, Maurice Herzog, and Marcel Schatz at Camp 2 on Annapurna I in 1950. Photo: Marcel Ichac

Descending in cruel conditions

On June 4, in worsening weather, the four climbers set out to descend to Camp 4 at 7,150m. It was a whiteout, with heavy snow and almost zero visibility. Rebuffat and Terray had removed their glacier goggles the previous day while searching for the route, and both were snowblind.

The situation was critical. Two blind men were guiding two weak, injured climbers. Rebuffat relied on his instincts and memory of the route to help navigate, but the party struggled to locate Camp 4, missing it in the fog and snow. Exhausted, the four climbers had to bivouac in a crevasse for the night.

Rebuffat on the arrow of the Pic du Roc in the Alps. Photo: Gaston Rebuffat

At dawn, on June 5, an avalanche poured into the crevasse, burying their boots and equipment. Rebuffat and Terray, still snowblind, dug frantically to recover their gear. Rebuffat was determined to keep the group moving.

Later that morning, teammate Marcel Schatz ascended from Camp 4 to search for them. Thankfully, he spotted the group and guided them to safety.

Rebuffat’s resilience

At Camp 4, Rebuffat was suffering early frostbite and snow blindness but coordinated the Sherpas’ evacuation of his companions.

On June 5, during their descent to Camp 2, Rebuffat helped rescue Herzog and two Sherpas from an avalanche. By the afternoon, the team reached Camp 2. Finally, everyone reached base camp alive, though Herzog and Lachenal lost some digits.

Rebuffat died from cancer on May 31, 1985, in Bobigny, France at age 64. Rebuffat’s tombstone in Chamonix’s old cemetery bears a quote from his book Les Horizons Gagnes:

“The mountaineer is a man who leads his body to where, one day, his eyes have looked.”

Rebuffat’s grave in the Chamonix cemetery. Photo: Wikipedia

Legacy

Rebuffat wrote over 20 books on mountaineering, including Starlight and Storm: The Ascent of the Six Great North Faces of the Alps, Mont Blanc to Everest, On Ice and Snow and Rock, The Mont Blanc Massif: The 100 Finest Routes, Men and the Matterhorn, and Between Heaven and Earth. He also edited a mountaineering column for Le Monde.

Rebuffat also produced numerous films, including: Flammes des Pierres, Etoiles et Tempetes (which won the Grand Prize at the Trento Film Festival), Entre Terre et Ciel, and Les Horizons Gagnes.

Rebuffat’s commitment to share the beauty of the mountains continues to resonate with climbers and adventurers. His routes in the Mont Blanc massif are still climbed, and his books remain classics.

You can watch the film Etoiles et Tempetes (in French) below: